Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Conversation: An Interview With Kavi Alexander of Water Lily Acoustics

Published on Mar 17, 2025

Today we have guest interviewer Ankur Razdan with an in depth, extensive interview with Kavi Alexander of Water Lily Acoustics, a Grammy Award winning record label.

AR: One thing I’m really curious about is when in your life did your attachment to music begin? And what was the first music that made a difference to you?

KA: Oh, that began as a child. My mother played Carnatic music on the violin, and she sang in the church. We were Christians. Tamil hymns, and English hymns. So this is where the love of music began.

She was a deeply religious lady, and she was always reading the Bible. And she was always telling me that the material pursuits are worthless and you should only seek the divine, on the understanding of course, that that was Christianity and Jesus. And she would quote from the Bible, she would read me stories from the Bible. She always said, I want you to be like King David, not the King, but the shepherd who was in the fields, the humble shepherd singing praises to the Lord on his harp. You know, the famous Psalms of David, the Lord is my shepherd and I shall not want.

So this is a very powerful…how shall we say? It’s a blessing. You can’t run away from this, and she had conceived this from a long time ago and she made up my name, Kavichandran. So you see, destiny has a very powerful say in the matter. And so this is where it all begins. This is why my company is called Water Lily Acoustics, because it’s named after her.

Yes, I think I’d read that. What do you mean when you say that she made up your name?

Well, you know, I’ve never, never, ever met anyone with this name. I have met people with the name Chandran and with the name Kavi, but together, no. Kavitha yes, and Kavisan and so on, but Kavinchandran, I have never seen that.

Interesting. Now, you’re Tamil. Are you from the Indian side or the Sri Lankan side of the water?

I’m from Sri Lanka. Where are you from?

I’m from Arizona, I’m half Indian. My father is Kashmiri, he was born in Delhi, actually. But I lived in Chennai for two years after college. I worked in a school there, teaching fifth standard and sixth standard Tamil students. So I’m not Tamil in any way. I got an uncle by marriage who’s Tamil, so I don’t have any cultural connection there, but it’s the part of India I kind of know best which is kind of strange. But anyways, did you say that your mother played the violin or you played the violin?

My mother, my mother. I don’t play any instruments. I have no musical skills whatsoever.

What kind of perspective do you feel like that gives you as a person who’s worked so closely with many gifted musicians?

I think that it gives me a sense of freedom, because I can ask questions which someone who knows music would never dare ask And I’ve noticed this when I say, why don’t we do this? And they’ll look at me like, are you kidding? And then I say, let’s try it. And then I hm, I see, yeah, it worked. So this I think, in a way, is a blessing.

Now, I read a quote of yours that you gave in the nineties, that at the time you said that you had two goals in founding Water Lily Acoustics. One was preserving Indian music from going extinct–

But not only Indian, but Asian music in general. Turkish, Chinese, Persian. With an emphasis on Indian because that’s what I was closest to and knew a semblance of.

For sure. And the other goal was, basically, the aspect of, of pairing Western musicians and Eastern musicians that I think that the label is so famous for.

Yes, to create this bridge, you know?

Yes, rather. Now what I’m interested in is how did they come about, both these goals? How did it come to occur to you that they were important and very worthwhile? Were they very solidly set in you from the very beginning, or?

Well, first of all I had a deep love of music instilled in me from my mother. And in Sri Lanka, we didn’t have any records, I used to listen to the radio. I still listen to the Tamil broadcasts, which was mostly Tamil film songs, with great singers like T. M. Soundararajan and Sirkazhi Govindarajan. And then Western radio. A lot of country music, actually.

Really. Who?

Yes, Elvis Presely and so on. I listened to the radio all the time. And then when I went to Paris in ‘68, I got my first stereo and I started to buy records. And I noticed that a lot of the Indian recordings, unless they were made in the West, they didn’t sound very good. Well, I must say this though. Indian EMI, or the Gramophone Company of India, made excellent recordings. It was mostly the vinyl which was poor quality. But the recordings themselves, a lot of them are very well done.

So anyway, I bought all the Folkways and Connoisseur and Lord Pacific and Le Chant du Monde and the Cora recordings I could find. And I noticed that the recordings were not as great as the Western records, like jazz or western classical music. So that was when I decided that this is what I want to do with my life, to start making recordings. So that was the real thrust.

And then the fusion stuff came later, partly inspired by reading about Baba Allauddin Khan and his Maihar Band, and also, you know, seeing [John] McCloughlin and people like that doing cross-cultural things. Actually, one of the first such things was Maurice Bejart’s ballet Bhakti. I saw that in the cinema in Paris, probably the greatest tribute ever made to Indian art in the west.

And then, I mean, I’m really going back to ‘65, the Edinburgh Jazz Festival. I think that’s the first time Indian musicians played in public with Western musicians, and they were already in collaboration. Khan Sahib [i.e., Baba Allauddin Khan] played with the wonderful English lute player…what the hell was his name? He is one of the most famous lute players…Julian Bream. My memory is leaving me….Anyway. So, you know, the precedent had already been set, and so I was just following in that line and trying to create something that would be worthwhile.

One of the things you said about listening to country music and Elvis on the radio over there gets to a question that I wanted to ask which is, I’m pretty familiar with, looking at Indian music and Asian music in general from the Western perspective and how that’s been very fascinating to people since at least the ‘60’s, you know, and I’m curious–I understand you were listening to some of the stuff but in general are people over there very interested in Western music, in a similar way that people are interested in Indian music here?

Well, I’m referring to English-speaking Sri Lankans at the time I was growing up. Many of them knew Elvis Presley because there were the movies and the radio. But the one that was loved unanimously–and this was not only limited to Sri Lanka, but also a lot of the English-speaking African countries–was Jim Reeves. Phenomenal voice, phenomenal. So everybody in Sri Lanka of a certain age group knows Jim Reeves and loves Jim Reeves. There was a very dear friend of mine, who’s passed away unfortunately, a very, very important student of Khan Sahib, he said: country music is ghazal. And he is absolutely right, it is ghazal. So that’s in my DNA, being attracted to that type of romantic, melodic music, you know? That’s what country music is. I mean, not this modern stuff but, you know, like George Jones and Lefty Frizzell, these incredible voices. And also Nashville produced some incredible instrumentalists, you know. And strangely enough, Nashville also made excellent recordings..They were pioneers, they got great sound. Really good sound.

That’s why Bob Dylan went down there.

Yes….well, I don’t think he was into sound. Because if you really listen to the early Bob Dylans recorded at Columbia, the sound is terrible. The harmonica–this was a big mistake a lot of them made. You hear this in the Paul Simon recordings. They were using the Neuman [microphone] close-up, and the harmonica would just rip your ears off. And I don’t think anybody noticed all this. But he went to Nashville because of the musicians. And, of course, the sound was the gravy. And you know, it’s interesting that double-album of his, Self Portrait, which everybody thinks is a piece of shit, is actually a fantastic album.

I agree.

And if you listen to it, you hear this beautiful, lush Nashville sound, and then suddenly this awful, tragic, wretched sound comes out. It’s Bob Dylan recorded live at Isle of Wight–

An awful version of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

It is terrible.But, you know, there are only, thank God, three or four songs like that and the rest of the album is done with Nashville musicians. With some exception. I think Al Cooper went there, you know, maybe the guy from the Band, Robbie Robertson. And also it was Bob Johnston, the producer, who had already worked with him in New York.

And then New Morning, also. “Girl from the North Country” with Johnny Cash. His friendship with Johnny Cash actually opened the door for him because, you know, at the time he went people in Nashville I don’t think were very happy with him with this sort of anti-war protest stuff. And I think Johnny Cash really helped to enable him to function there.

I’m sure it did, and I’m glad to hear that we’ve got very similar views on Bob Dylan. I also love New Morning, it’s a great record. But that makes me think–

You know the one with one of our brothers, one of our soul brothers on the cover? Purna Das Baul on the cover.

Really? Oh, on John Wesley Harding.

Yes, yes. Baul, and his son.

He looks so confused to be there.

Wearing some kind of a bathrobe. Wonderful man, wonderful tradition, you know, the Bauls. They are the blues singers of India, they really are the bluesmen. When I say blues, like Delta. But the upper classes didn’t entertain these guys because they were low lives and untouchable and what not. But Rabindranath Tagore became friends with the father of Chandi Das Baul, who’s Nabani Das Baul. And that kind of then allowed the upper class, the upper crust Bengalis to appreciate the Baul poetry. But it’s more than poetry, it’s a whole tradition. They fused Islam and Sufism and Hinduism, and it’s incredible. They were hippies before, long before the hippies.

In fact, it was because Allen Ginsburg had gone to India and he’d somehow found out–and he’d heard some Bauls, and he realized the connection, that here these are the original hippies, the original bluesman. And he came back to the states and he got, I think, Albert Grossman involved, Bob Dylan’s manager. And they brought this troupe from India and they were gonna do a little tour as a stage production called Lila, and I think it fell apart.

Anyways, they ended up living out of Grossman’s upstate New York property, which is where they met the Band. And the first of the Bauls done in the US was done by Garth Hudson of the Band, at Big Pink. I think they recorded for Nonesuch [Records.] Those recordings were done by my hero, David B. Jones, who recorded phenomenal stuff on Nonesuch. Carnatic music.

So there’s two recordings of the Bauls on Nonesuch. And the one [recorded] by Garth Hudson was released on Elektra [Records.] Garth Hudson’s recording isn’t anywhere near David B. Jones. David B. Jones was fantastic, he’s a hero of mine.

That makes me think as well, once you were in there recording, does recording Indian music or any other kind of Asian music require different techniques? Did you have to do anything different?

No, I just used [UNINTELLIGABLE 15:15] And I was very, very lucky to have met him, and got him to make me the custom tube-chain. And I had very good friends at Milab Microphone Company, and I was able to get the rectangular capsules from them. And that was an amazing recording chain that sounded wonderful. Impractical, but the sonics were fabulous.

Look, we are not that high-production. We had one night. One night, to get it right, okay? And these are the limitations under which I had to work. But, you know, maybe that also was a kind of a gift, because it put a certain type of pressure on the musicians to yield the goods. And there’s no fixing in the mix, because there is no mix. I remember, I don’t know if it was Bela Fleck or Jerry Douglas, but they walk into this church, and they’re like: woo-hoo-ha. Like, very confused.

Yeah? They had never recorded in a church before?

No! And certainly not the way I did, with just two microphones placed at a certain distance away.

I think it’s coming back. There’s a trio, Miranda Lambert, and two other guys, Texans, have made a record with two mics. It will never become the norm, because they are used to polishing and polishing and polishing. So that will never happen. Now, I understand the Berlin Philharmonic has issued some stereo recordings direct-to-disc–not even analogue tape, direct-to-disc. But this is all just fad. And now with all this Pro Tools and all this digital stuff, there’s no going back. I think very few people are recording analogue.

Unless they want to set limits on themselves, possibly.

No, unless they want the sound.

Well, like you said, that artistic pressure sometimes can be good.

Well, you know, there is very little art today, to be honest, man. I mean, look around you, whether it’s movies or literature, or music as well….Mainstream popular music died after 1972.

Oh, I think it made it to 1998.

Western Classical I think is still strong, we have lots of amazing soloists coming out. A lot of them from the far east–you know what is interesting, there are a lot of violinists, mostly female, in Korea and Japan. But not a single Indian! No Indians. The only token Indian is Zubin Mehta the conductor. There are oddball others. I met a Goanese Indian in the Atlanta Symphony many years ago, so I’m sure there are one or two here-there sprinkled. But there is no Indian firebrand leading the church. No, it doesn’t exist. I don’t know why. But that’s a reality. Except for the one exception, and he’s at the very top. One of the great producers of western classical music, Suvi Raj Grubb–a Tamil, by the way, from Madras.

Who?

Suvi Raj Grubb. He was staff producer at EMI. He’s a hero for me.

So when you said that you recorded with just two mics, would that basically be you’d have the stereo sound, but then there’s no separation between any of the instruments?

No, you get your balance by moving the musicians around a little bit in that space, and taking into consideration the reverb of the space, and getting the mic to the ideal spot. Not too far, not too close, you know.

When you started to bring Asian musicians together with western musicians, what did you find that the Indian and Asian musicians thought about the whole process?

Some of them had some understanding of the western musicians or understanding of Indian music, and some of them had nothing, but they had improvisational skills so they jumped into it. It was all improvised, you know, so it worked. But before I did the east-west, the first–for want of a better word–the first fusion I did was with a west African Creole, from Gambia playing kora and singing with two gospel singers. And of course, it went by the wayside, because nobody knew them, they were not name-artists.

Was that on Water Lily or one of the earlier labels?

Of course, yeah, on Water Lily. I’m very proud of that record.

What was it like starting such a unique record label in America in the eighties?

Well, I mean, when I started the record label, there was no question of ‘unique’, just the question of start the label, get it going. You know, I wasn’t thinking of ending up on the map as a unique label or anything like that. I just wanted to…You know, I was fascinatingly in love with music and I wanted to record. There was no agenda, there was no plan, there was no let’s win a Grammy, let’s make a lot of money and let’s–no, no, not at all like that. I was on a bicycle with a cardboard box on the back, going to the post office and mailing one LP here and two LP’s there.

Well, that’s what I mean. Tell me more about that, the early years.

Well, nothing has changed. Except I don’t even have a bicycle anymore.

How long did it take you to get your own office?

I don’t have an office I never had an office.

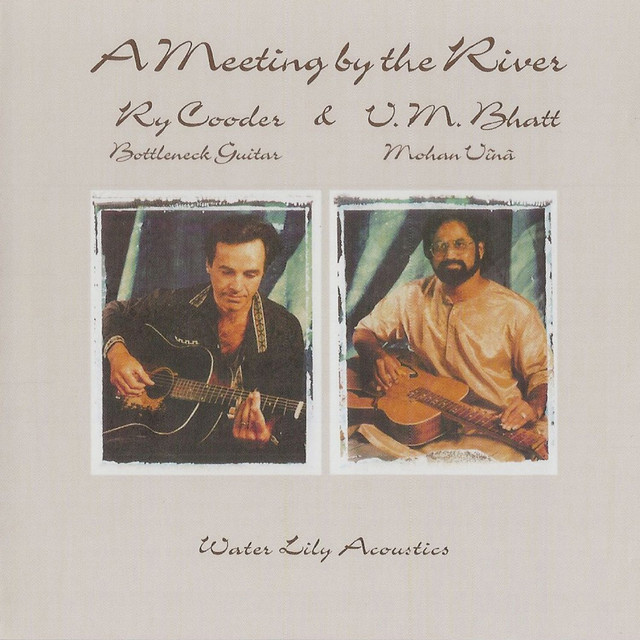

There you go. The church space that you recorded “A Meeting by the River” in, was it like an operational church?

It was part of a seminary that had been shut down. And so it was used only on Sunday. There was a small group of Catholics who came to that church on Sunday. So I could go in there on a Sunday afternoon, and stay there the whole week. And since it was sort of off the main path, there were no weddings or funerals and all the stuff that goes on in a church.

Well, at least there was music.

So, it was fantastic and the priest and I got along. And there were tons of musicians. There were Tibetans coming in there, Turks coming in there. Africans coming in there, Indians, Chinese, Persians. Unbelievable.

I can’t remember if you mentioned earlier his name, but I’ve read that you worked in the early days with an engineer, somebody named Tim Parivicini, do I have that right?

No, he built the equipment that I used, at my request. He’s not a recording engineer, he had the skill to do that. But he was really an equipment designer, and I befriended him and had him build me the custom tube mics and the rest of the chain.

And why did you feel like you needed that or wanted that?

Because I liked the sound of vacuum tubes. And of course, at that time, there was very little you could buy, there were no new tube mics available at that time. So this was why I approached him, and he agreed. I got him the capsules from Sweden and he built me the mic, and then my pre-amp, and then he built me, basically, it’s a Studer, a tube Studer, that he modified. And it was an unusual standard, a one-inch two track. This didn’t exist: there were one-inch four tracks and one-inch eight tracks, but no one-inch two track. One-inch half track, yes, but no one-inch two tracks. This machine was the first.

When “A Meeting by the River” won the Grammy, I’m sure that must have changed things.

It started to make me money. And that allowed me to then splurge on all the stuff that I’d been thinking about, you know? That I wanted to do.

Like what?

All these projects I wanted to do. More music.

Now, that album was recorded, I think the year before I was born, I’m thirty.

Ha!

I know, right? So I first encountered that record as a CD, my dad had it. And I also remember growing up, once I listened to it, I heard stories about him and my grandmother seeing the tour. I can’t remember if Ry Cooder went on the tour or if it was just Bhatt.

No, no, they never went on a tour. I think you’re mixing it up with “Buena Vista Social Club,” which was a record he made afterward with Cuban musicians.

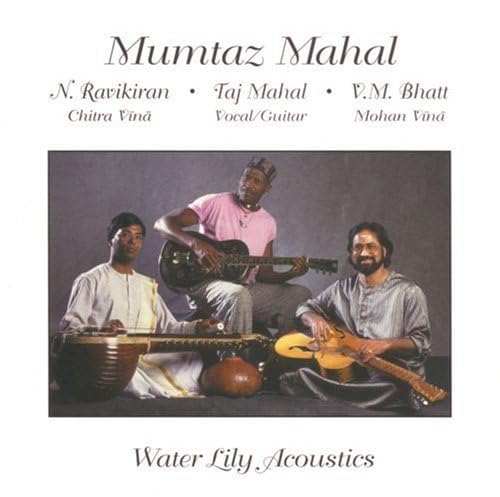

Well, I’m sure you’re right that they didn’t go on tour, but it was some Indian musician that they saw because it was certainly not Cuban musicians. But regardless, if there was no tour, then never mind. Another record on Water Lily that I really, really admire, that I think is quite beautiful, is “Mumtaz Mahal” with Taj Mahal.

Now that one was nowhere near as successful as “A Meeting by the River.” For some reason, nobody likes that.

It’s still very lovely.

There’s another one I did with James Newton, who’s been awarded Jazz-flutist-of-the-year by Downbeat for, I don’t, forever. I recorded him with Kadri Gopalnath, who’s a Carnatic saxophone player. I think it’s a fabulous record. I cannot give it away, nobody wants it. Or that African Creole, the gospel singer. Now there’s another beautiful record with a wonderful English guitarist by the name of Martin Simpson, who I recorded with a virtuoso Chinese pipa player called Wu Man. Again, it’s a beautiful record, it’s called “Music for the Motherless Child.” Nobody wants it.

I’m sure there’s an element of chance to these things. Do you have any memories that stand out in particular to you from the recording of “Mumtaz Mahal” though?

Yeah, it was great fun. You know, Taj, I had met him in Sweden many years before, even before Water Lily existed. It was only an idea I was thinking of, going to America, and starting my record label. I went to see him in the small town where he lived in Sweden, and I met him after a concert. And then I went to his hotel room and we stayed up all night talking. At the time I had proposed recording him with L. Subramaniam, and to make a connection with Madagascar, the music of Madagascar, in Africa. Much later, this was exploited by David Lindley and Henry Kaiser.

So this would have been like ‘78, ‘79 when I met him in Sweden. And I talked to him about making this recording, using musicians from Madagascar and Dr. L. Subramanian. Of course, that never happened. And then I picked it up when I came to the US. I didn’t have the resources to bring musicians from Madagascar to the United States, and I didn’t have the resources to go there. So used what I had, which was Bhatt. So it was unusual because “A Meeting by the River,” both the Indian musicians are Hindustani musicians. On “Mumtaz Mahal” are Hindustani and Carnatic.

A different kind of fusion.

Yeah. These have not yet been released, but the ones that I’m really truly proud of are the ones I did with Indian and Chinese musicians. So there are Carnatic and Chinese, Hindustani and Chinese, and Indian and Persian, and Indian and Arab. These to me are truly, truly exceptional recordings.

Are those your favorite that Water Lily produced?

Some of my favorites, yeah. But those have not been released yet. They were recorded some time ago. But then they’ve never seen the light of day. But they will soon. Those are fantastic. The Persian and Carnatic, and Persian and Hindustani, and Chinese and Carnatic. There is a recording I did with Vishwa Mohan Bhatt and this phenomenal Chinese girl who plays, she’s on the CD with Bella Fleck.

I think I’ve heard that one.

But this one is not out, the one with Bhatt and Jie-Bing Chen. It’s called “Silk Jade and the Begging Ball.” It’s unbelievable.

Yeah, I think the one I heard is one of the ones you did put out with Fleck and Bhatt and then an Asian, or Chinese, instrumentalist. [The record, featuring Chen, Bhatt, and Fleck, is called “Tabula Rasa”] But that sounds interesting. Do you have, like, very deep archives that you’re trying to get everything worthwhile out of, or is it just a few special projects?

It will all come out. It’s all money. And the other thing is when I look at the records and, you know, only certain things sell because they’re the ones people like and they’re the ones people write about, then it’s not very encouraging. And yet I have gone ahead and made these because I believe in the music, I believe in these things. And one has to do what one can, you know?

It’s true, it’s true.

And also, you know, I’m a big lover of symphonic music.

Sure, clearly.

Yeah, I’ve recorded quite a few symphonies.

Hell yeah. What was it like working with Subramanian?

Wonderful. As it was with Khan Sahib. Both Subramanian and he were the first Indian musicians I recorded, and they were both exceedingly kind and generous, and helped me to get on my feet. And strangely enough, when I went to see Subramanian in LA, Water Lily didn’t even exist, it was only an idea. I went to see him and he was very gracious. It turned out that, even though he is South Indian, his family had lived in Sri Lanka, because his father taught Carnatic music. And it turned out–I didn’t know this–that the school, a very prestigious school called JASPA College in the north of Sri Lanka, the principal was a relative of mine. So when Mani found out I was related to this man, whose daughter had studied with the father, that kind of cemented a link between us.

Interesting. I was just about to ask if there was an affinity for this violin-playing Tamil guy, and clearly there was. And not just an affinity but a connection.

I listened today to one of his records on Water Lily, “Electric Modes,” if you recall that one. And I couldn’t figure out why it was called that, was his violin like an electric violin on that recording?

Yeah, when I met Mani, he had been playing with big names. Fusion artists, you know. He was playing with people like Maynard Ferguson and all this…so he had gone electric. And I didn’t like the electric violin. But I didn’t have the clout to say ‘look, this is how it’s going to be,’ because first of all I didn’t have any money to pay him. And he’s obliging and kind enough to record for me, so I can’t say ‘look.’ So I had to wean him slowly…it was a whole process. So we got electric, and the second recording I got him a tube amp, and then the third recording dead-on I got him to go back to playing acoustic violin. At least on my recordings. So “Electric Modes” is a salute to the great Muddy Waters album called “Electric Mud.”

That’s a salute to a great master who I admire and revere. I think that album was a turning point, you know? So “Electric Modes” was an apt title. He’s using all kinds of fancy stuff, little boxes, I think they’re called pedals or whatever. And it’s electronically processed. The next one, he got rid of all the processing, but it was still electric. I got him a tube amp from Seymour Duncan, they were kind enough to loan me a tube. So that’s the second one, that’s “Kalyani.” And then “Sarasvati” is all acoustic violin. And then the one I did with him and V.G. Jog, which is unreleased, is all acoustic. The one, that is released, with Larry Coreal is all acoustic.

“Electric Mud” was a turning point, in your opinion?

“Electric Mud” was definitely a milestone album. A lot of people don’t like it, I don’t know why, but they thought it was stupid. Well, look, I don’t know, people can have their opinion, but I think “Electric Mud” is a historic record no matter what anybody says. And Muddy Waters is the grand-daddy of ‘em, he’s an amazing man who should be honored a lot more than unfortunately is.

He rather should, he rather should. I’ll have to go back and listen to “Electric Mud” again. I did hear it once a couple of years ago and I have to say, I wasn’t as impressed by it as I was with some of his other recordings. But maybe I need new ears to hear it.

Now, I’m curious if, in terms of western musicians learning how to play in different styles from Asia and from India, you know of any good resources for people who are trying to learn more about that kind of thing? Besides listening to records by Water Lily Acoustics.

No, I am sorry, I am not aware of any. But if you want to study, I would send you in the direction of the Alam Madinah School in San Rafael. Because remember, Alam Kahn, erstwhile son of the lion of my heart, plays in a rock band as well as the sarod….I mean, heavy, heavy rock. I’ve never heard this band. I remember I was visiting and he was upstairs taking lessons. I had to wait till the lessons were over and he comes down the stairs and he kisses his mom and he picks up his electric guitar, and his mom and I had a good laugh. But I have a feeling it’s pretty and loud stuff. And you know, he’s born here, he’s American. I think that anyone who wants to explore that, I think that’s the best place I can think of.

What was the name of that school again?

Alam Madinah School of Music, it’s Ali Akbar Khan’s school in Marin, in San Rafael.

Okay, that’s interesting to know. I do ask that of personal interest because I’ve tried to look up, you know, books on Indian music theory or whatever and I cannot find anything worthwhile in English.

Don’t waste your time. Go to the source. And Allam is a wonderful, wonderful man. He’s been raised by a great man who has taught his son, not just the music, but the real deep spiritual essence behind this music. How to be an honorable human being. Which you don’t find in the popular music world. You have to be a man of character and grace, and Allam is. He’s been taught by the best, and I’m very proud, very happy to see him the way he is. He’s a great guy. Very wonderful man, great teacher, great musician. So if you want to learn about western music and Indian music, I cannot think of anyone better than him. Or more qualified than he is. He’s listening to all the cutting-edge American stuff, and as a student of a really complex microtonal music, he is able to hear through the muck and the mirage and the mystical beauty. So I would say if you want to walk along that line, go to Marin, San Rafael. It’s a beautiful place.

And there is also another prominent and incredible reservoir of knowledge, Swapan Chaudhuri, the great tabla player, who had accompanied Khan Sahib for a great many, many years, a wonderful, wonderful man. Very gentle, kind. He reflects the essence of what Indian culture and music are about. First and foremost, to be an honorable human being.

That is what the music is about in a way, being human.

That’s what everything is about. First and foremost, you have to get your act together and you have to behave like an enlightened human being, and not as a barbarian.

I think that we come here with a limited amount of time to do certain things, and some of us, I do think, can leave behind a little legacy that can inspire others, set them off on other quests. So I think the first thing, the first lesson is to master the art of making excellent masala chai. If you can master that, then everything falls into place.

Well, I don’t know about that, but I can cook some pretty good Kashmiri food. Another thing that I would like to know, you’ve mentioned the archival stuff that you’re trying to get out there. Are you working on anything else right now?

No, I haven’t made a recording in almost fifteen years, twenty years. I just don’t have any money. I’m going to be seventy-four in May.

My drive–I mean, sometimes I sit there at night and think, how the hell did I do this? I remember recording an organ and trumpet, western classical. And we had this church with the largest pipe organ in California. The high end, about twenty feet from the ground. So if you played the trumpet at the bottom, you know, everything is above him. So I went to an industrial place and I rented scaffolding. And I built the scaffold, to the horror of the people, because this scaffolding was covered with concrete and cement. And the trumpet player hated it, because he had to climb this rickety damn ladder that was part of the scaffold, to get about thirty feet up in the air.

So there were things like that. I can’t believe I did that. I didn’t build the scaffold alone. I had somebody who drove me to the rental place in a van, you know, things like that. Booking the tickets and making sure the artists are all picked up on time….It’s like being in the army and running a campaign. I can’t believe I did it. But we have the proof in the recordings.

You do, and thank God you did.

And there were a lot of people who helped me, wonderful people. The support staff.

Do you have one single favorite recording of Indian music? That’s your top?

Do you mean mine or others?

Others. I mean, that you’re personally a fan of,

Oh, Khan Sahib. All the recordings of Khan Sahib released on Connoisseur Society. Recorded by the famous David B. Jones. All two-tracks, by the way, all two-tracks. And recorded in a church. The Connoisseur Society, There were I think seven titles all together.

I’ll have to look them up. Kavi, I think that’s all the questions I have for you now, but I want to thank you. Not just for–

Aren’t you going to ask me how much money I have in my Swiss bank account?

Well, I know it’s a lot, you won a Grammy in the nineties!**

Oh yeah, sure. I couldn’t dig a ditch in the backyard and fill it with water and pretend it’s a swimming pool. No, no, no, no.

If you piss in it you might be able to pretend.

Well, I don’t know about that, we’re too poor to even piss!

But listen, actually on a serious note, besides thanking you for taking the time to talk, I wanna let you know that in my opinion, everything, all the crazy things you did were worth it because… not just the “Meeting by the River” record, which obviously many people know and that’s the first one on your label that I heard, because it was in my living room growing up…but so many of the records really have been…speaking personally, as a half-Indian, half-white guy who was raised not very Indian, but pretty American, over in Arizona–to have that connection, to be able to explore it and listen to these records and have…I mean, it’s almost not even about my own personal heritage so much as just my musical vocabulary being grown. You know, the other day, I was playing some lead guitar and my brother heard it and he said, oh, that kind of sounds like that Indian CD we had when we were kids. And I was like, yeah, because I was trying to play like Bhatt, on that record. Or Cooder, I’m not sure which one. So, I know sometimes it feels like you don’t have a ditch to piss in, but there are a lot of people who’ve heard these records and not just that one that won the Grammy. And they’re weaving their fingers through other people’s minds and ears….

These musicians were absolutely gracious. I mean, Ry Cooder was incredibly kind. Every musician I worked with, whether Indian or American or Chinese or Persian, they all were without exception exceedingly kind and generous.

They get it, I think.

You know, whether they got it or not, they were up to the task. They’re musicians, and they might be thinking, my God, this man is totally mad. But yet, they rolled up their sleeves and went at it. You know? And I think many times they were surprised, pleasantly surprised.

By the results?

Because they weren’t expecting–because it’d never been tried. So they never heard anything like it, and it was unfolding right before them. Then that became a challenge, that became a heady drug. It really messed with them in a very beautiful and positive way.

So I was very lucky to witness that. I mean, most of the time I wasn’t witnessing it because I was in the back room recording.

You were working!

Ry Cooder told me many times, he said, buy yourself a little camera and film this stuff. I wish I had. The conversations, some of them are on the tape. But, you know, the conversations that took place after a tape had been over, and all the laughter. Ah, it was so much fun. And then to pile into a van and go and eat….It was really an amazing time. And there are nights I wake up and say, how the hell did I do all this? Of course, I had an incredible support staff, because I don’t drive. So I had a friend of mine who had a van, and he was my right hand man. And the equipment was very heavy. The mic stand alone weighed a hundred pounds, okay? It was a stand that they use, with lights on, in rock concerts, right? It’s telescopic, up to sixty feet or ninety feet, very heavy. And the tape recorder weighed two hundred pounds.

Everything was all streamlined. We had it down, man, it was like a military operation. We’d rent these vans from Enterprise and take the seats out, move all the equipment into the church, put the seats back, then go pick up the musicians. It was unbelievable.

And you made it happen, you made it happen.

It happened. There was a momentum, it took on a life of its own. And many people were very generous and kind and helped me technically, financially.

There was a dear friend of mine, a well-to-do Indian audiophile music clubber. He gave me a lot of money. He helped me. So a lot of people helped me in many ways, and if not for them, none of this would have happened. None of this.

It takes a lot of people to make something happen.

Yeah. The musicians….So anyways, that’s the long story short. You got what you want. I would recommend that you check out Southern Brothers.

I’ll do that.

That’s the one with James Newton and an Indian Carnatic musician who plays saxophone.

Okay. That sounds fun.

This guy’s a monster, man. I mean, he really should have played with Coltrane. Amazing guy. Amazing. These are saxophones made in India. And what is amazing is, there’s no key noise.

From clicking them or pushing them down?

Yeah, when you open and close, they make noise. It’s all held together with rubber bands and stuff. Unbelievable. And his tone. He was a very devoted man. He was deeply religious, very devoted, and he had internalized this to a degree that he had a childlike quality to him too. He wasn’t looking like, hm well, you know, what can I get out of this? What can I squeeze out of this? You know? None of that. He’s just like a kid. And I think that’s the way you have to be.

To make good music, I agree. You can’t be self-conscious about it.

A state of innocence, you know. And he was fabulous. He really was. Unfortunately, he passed away, man. I don’t know why, you know, we South Asians are prone to heart disease and diabetes. And so generally we don’t live very long. And also, if you’re a traveling musician that totally ruins your life.

Yeah, I’ve heard it’s hell.

Eating strange food at strange times and hours. But anyway, I’m really very pleased that I was able in a small way to pay homage to an incredible tradition. The Indian–the entire eastern body of music. Indian, Chinese, Persian, Arab, Turkish. To have had the blessing to record these great traditions. You know, I remember I was recording these Tibetan monks. These are real tibetans, right. They come out of the monster, they come with an abbot. An elderly man. He watches me, I’m having the monks move around. And he walks up to me–he must have been at least ten to fifteen years older than me at that time–he walked straight up and, you know what he did? He pulled my beard.

Really?

It was unbelievable, unbelievable. You know, very childlike. A nice joke.

Yeah. No, I mean, I agree. That’s how you gotta be. And it’s not just about music, it’s all the time. To enter that, not childish, but childlike state….

Yes, exactly. You made the correct distinction there. And that’s the state of mind, you know.

To make good music and make a good record.

He wasn’t performing, he just came as the abbot. He didn’t sing. There were nine young monks who sang. He figured, okay, this is the boss on the other side. So let me go over and say hello to him. And he did what he did.

Well, I guess some records need a producer and some need a priest.

A shaman, I think, a shaman. A conjuring shaman.

Someone to provide oversight at the very least.

Who’s blowing the tobacco mixed with some hallucinogen up your nose through a long bamboo tube.

Damn straight, damn straight. Now, Kavi, I’ve gone through all my scripted questions. Is there anything else that you feel like you wished I had asked about or that you wanna talk about?

Actually, no, except for the secrets of masala chai, and cooking in clay pots. I’m a big fan of cooking in clay pots and eating with my hands.

Sure, just like my dad.

Yeah, it’s the only way, man. You know, they have done some studies now, they found that eating off banana leaves has some special thing going on there.

I’ll have to look into it. I only eat with my hands if I’m eating biryani. But anyways, thank you for the time.

You know what, you need to do me a favor, and when you publish this,make sure you give out Ali Akhbar Khan’s school address. If somebody else listening to this wants to think of considering going to his college. So I want you to have that available on your post, right? Because you will be honoring the great Baba Allauddin Khan and his tradition, and the torch bearer today,, Alam. Wonderful, just an incredible kid.

Ali Akhbar Khan and I were very, very close, very close. And he really was like a father to me. Truly, truly exceptional, that was an unbelievable gift, my relationship with him. So okay, my friend, thank you very much, and I’m happy that you have been enjoying my little contribution to mankind.

I’ll go on doing it.

Thank you. And check out the one called “A Gathering of Elders.” You might find a used copy somewhere for two-three dollars, nobody wants it. That’s the one with the West African Creole and the gospel singers. And that’s really the first Water Lily cross-cultural recordings. Before that it was all straight ahead Carnatic or Hindustani or Western Classical music.

Does the online store on Water Lily Acoustics dot com still work?

No, there’s no online store. There’s a website, but I don’t like the internet. You would have to find it on Amazon or some used record store somewhere. And, you know, we only pressed a thousand copies. But they didn’t sell, so it was never reprinted. And out of the thousand, many of them went to the artists. Very little got sold. So finding a used copy is like looking for a needle in a haystack. because it’s so rare. Who knows? Maybe you might find a copy.

If I find it, I’ll let you know that I did. Sound like a plan?

Yes. Listen to it first, then let me know.

Yeah, no, I would do that, I would do that. I’ll tell you what I think of it, too.

Okay. Thank you very much, Kavi. Have a good night.

You, too. Take care. God bless.

Ankur Razdan is the leader of Washington, DC folk-rock group Different Answers. He can be followed for his musical micro-reviews on Twitter at @mukkuthani or for his band on Instagram at @differentanswersband, and corresponded with by email at ankurmrazdan@gmail.com.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal