On Peter Gabriel's "Melt" and Steve Biko

Published on Feb 21, 2026

Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: 23 North: A Travelogue of Record Shopping in Ohio

by Madison Jamar

In January of 2024, a month before I turned 30, I acquired a passport for the first time. The process was arduous because I lament interfacing with bureaucracy of any sort. I’m often inclined to wait until the last minute to file appropriate paperwork, in this case about a month before I was set to fly to France with my partner. Our plan came together in a frenzy, under the pretense that it was for his work.

The trip was our first together as a couple, a year into our dating and I had the notion that it was to be a test of our durability. How would we manage each other’s quirks when uncovered, under the stressors of international travel to a place where neither of us spoke the language? We fared well enough, leaning into saccharine romance under Gothic architecture and aloof, cool Parisian attitudes. Though we fought, seeding conflict that would take root for the next couple of months.

Like me, it was my boyfriend’s first time traveling outside the continental United States with the exception of visiting Montreal and Quebec as a child. I think back to my early days in college and remember the incredulous faces of new friends and classmates when I stated that I didn’t have a passport because I’d never been out of the country. Not even to Canada or Mexico? was a common retort I found perplexing. No, I’d say, not even to Canada or Mexico.

Besides, I am from central Ohio, home to the capital, Columbus, a ways from either border. Growing up, I knew little of flight that could carry one over the stretches of flat plains. I knew of vehicles, exhausting over miles of paved roads and tired feet treading along roadsides not meant for walking. I could point to the north—the cities Lewis Center and Delaware (a city and county in Ohio, not the home state of a former genocidal president) in a county entirely separate from Columbus—as the place where I grew up, suburbs, increasingly populated by the upper-middle class crest.

But to say I’m from Columbus feels the most encompassing. I was born in Riverside hospital and my extended family of too many people to accurately count, resided mostly on the east side of the city. During summers, my sister and I walked to Franklin Park with our cousins from our eldest aunt’s house where we picked rabbit’s ear. We moved from the house I don’t remember on Minnesota Road to apartments in Worthington, Westerville, and low income housing on the west side, near the Hilltops, before maintaining a near decade long stay of residency in an apartment complex in Lewis Center. I showcased my independence by braving ComFest (Community Festival) in the Short North with my friends. It’s like Woodstock, we told ourselves and each other.

By then, in late high school, I was self-aware enough to know that the actual Woodstock Festival of 1969 would likely not have appealed to me given the chance to attend: mud, grass (to which I’m severely allergic), a seeming lack of bathrooms let alone clean ones, camping, flailing hippies. But it was graced by musicians including Janis Joplin, Santana, and The Band, artists and the like who I discovered on the cusp of adolescence and who I held in reverence.

The trajectory of my dive into classic rock fandom is now hazy. While I know that it was a conscious decision to explore the genre, aided by my love of Jack Black’s pedantic metal head character in School of Rock and then newly found interest in bands like Fall Out Boy. The discoveries that were etched plainly in my memory, as I found a new musician or band to extoll have now devolved into a series of imprecise snippets of reminiscence.

What I do remember: my mother coming into the bedroom I shared with my older sister on my thirteenth birthday to reveal that I would not be going to school that day. She didn’t ask what I wanted to do but told me to get dressed after waking in the late morning. As we drove down the freeway along the route we typically took to visit my aunts, I could see we were headed downtown and then towards Ohio State University campus.

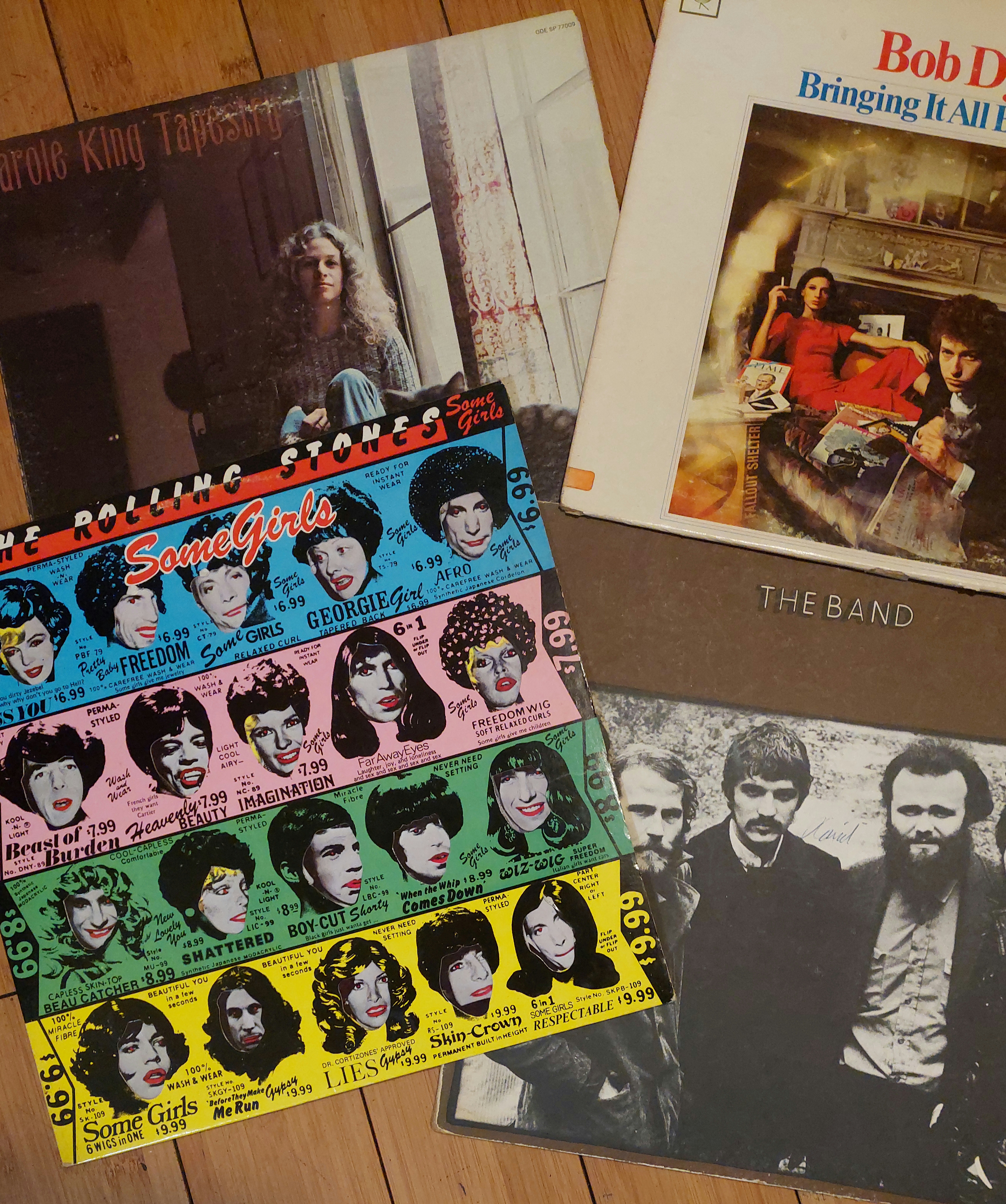

After selecting a book at the OSU bookstore, a Barnes and Noble, my mom walked us to a storefront I didn’t recognize on the corner of North High Street and Chitteden. Above the entryway into the store, signage announced, “SINGING DOG CD LPS BUY USED AND NEW.” Inside, I paced up the aisles flipping through the rowsof records. I took my time, wanting to see every object for sale: the large scale posters of the Pink Floyd back catalog painted on the backs of women*, Banquet for Beggars* on vinyl, a black white image of Bob Dylan looking up from an enclosed case of glass among other more expensive items.

I searched for an hour, unsure of what I wanted until I saw it, I picked up the CD, The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Smash Hits. The compilation album—which I didn’t yet understand to be a marketing ploy that repackages popular work to be resold rather than official studio projects—served as an adequate sampler of Hendrix. I was committed to liking the musician, after learning he was hailed as one of the greatest guitarists, which really may have been of little significance to me had he not also been Black.

I approached the check-out counter, staffed by a man who I assumed to be the owner, an older man with long gray-white hair and a thick beard. An archetype I would begin to know as, The Record Store Guy. I just love when young people buy this old stuff, he told my mother. I beamed under the affirmation before asking if he could order me a Fall Out Boy CD.

Smash Hits opened with the familiar riff of “Purple Haze” but it was when the album reached the sixth track that I became transfixed. “All Along the Watchtower,” originally released on The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s final record, Electriclady Land, carried over the speakers as the guitars weaved over from left to right, enveloping my mom and I as we drove back up north on 270.

Several years later, at 18, much of my classic rock proclivities would begin to be supplanted by indie, but I’d returned to Smash Hits, and “All Along the Watchtower.” Towards the end of the song the words become unclear under the overlay of guitar licks. Where Hendrix might be singing gotta beware, repeatedly, I heard, gotta get away, gotta get away, I will. In a car of my own, I would increase the volume high, screaming the words as I understood them, driving up and down Ohio’s many highways and backroads.

*

As the start of the year saw my first international and coupled vacation, the holidays brought about my first trip back to Ohio where I’d stay on my own. Often I skip December trips to Ohio, relishing instead in the hush that settles into New York City after the frenetic energythat takes hold towards the end of November dispels**.** But I couldn’t remember the last time I spent the holidays in Columbus. It was certainly before 2020 and likely before the fifth birthday of my twin niece and nephew who would be 10 in January.

I booked eight days in an apartment in Victorian Village and rented a car, neither of which saved much money but offered a space of retreat from family and a freedom to traverse across the city on my own schedule. But after a decade and change of traveling by subway or in the back of cars, my confidence in the driver’s seat had wavered.

Eleven years ago, I worked a job I loathed and was living in a place that operated somewhere between a women’s shelter and a boarding house. I was ashamed, angry, and uncertain if the future I was telling everyone about would ever occur. In short, I was nineteen. Everything, bad as it may have been, felt worse than it probably was.

My car at the time, a 2009 white Chevy Cobalt, was a harbor. In the car, I didn’t mind all that much being stuck in rush hour traffic and often took the long way back to Delaware after a double shift at work. It was the early 2010s and iPods and MP3 players had made albums more portable than ever, rendering physical copies less profitable. But I still bought and used CDs, toggling between the player in the stereo and the local independent radio station that sponsored concerts. The Chevy transported me to these shows and to the record stores I discovered including and beyond Singing Dog, that I had continued to find comfort in. Columbus, I learned in my teens, was home to an eclectic blend of music scenes, connecting ships, radio and live venues.

But Singing Dog closed sixteen years ago and after 33 years and several dial changes, the local indie rock station permanently left the waves early in 2024. I was unfamiliar with the radio presets on the blue Hyundai Electra I’d rented**,** and changing the station while driving came with difficulty. The soothing dark roads, unlit except by the headlights of cars now appeared dangerous and long stretches of freeway were endured. Since my first year of undergrad, I’d bemoaned Columbus’s changes—what the city championed as revitalization often shrouded its aggressive welcoming of gentrification. Yet, who I was to demand a place I fled, to remain in stasis for my infrequent returns?

My planning of this trip was again frantic, coming together in the third week of December. This time boggled down less by bureaucracy than I was by my own disorganization. The final quarter of the year, like its predecessor, had beat my ass. At 2023’s end, I was in shock, trying to reconcile the death of a friend who I loved but had not been close with in recent years. My pain felt without merit. Guilt would not let me mourn. Such intellectualizing safeguarded me from fully accepting that his death had transpired.

When I finally looked into the chasms of my grief, the grace period for sadness it seemed, had expired. Tensions at my primary job between my boss and me resulting from errors made by and falsely attributed to me, had reached an apex. My systems were off kilter. How could I explain? I hope this email finds you well! I’ve come to the obvious realization that death is permanent and that’s fucked. I lost my wallet and forgot to book a vision exam to renew my license. My secondary job, assisting an artist I long admired, dissolved in the wake of her sudden passing, dredging up the leaden sensation of mourning. I trudged toward the hope of a new year, though it felt like I was running in quicksand.

These frank realities collided with my recollections of the Columbus I’d once inhabited and the materiality of the city I now experience.

*

Record stores were not the primary places I went to collect music as a teen. I sought music media from any place with a CD section: Target, Walmart, Barnes and Noble, Meijer. These stores were plentiful across Central Ohio and most had locations within a few minutes of our apartment. Yet, save for thrift stores like GoodWill, they offered only new and/or popular music.

In their standardized uniformity, chain stores lacked the coolness I associated with record stores which I visited only on special occasions or when my mom felt like driving. Unlike a Walmart or Target, you could interface with the stewards of the independent shops, the employees and owners who were often eager to discuss your purchases not merely to sell you more but to understand your interests.

Though it may bring to mind a man, perhaps middle-aged, the Record Store Guys exists cross-generationally and across genders. The archetype exists canonically in the pontificating John Cusack in High Fidelity. But I found it also in Molly Ringwold’s Andie of Pretty in Pink, who works at the fictional Trax owned by the spunky Iona (Annie Potts) and even in Kate Hudson’s Penny Lane, advising that if you ever get lonely, go to the record store to visit your friends.

I had strived to be a Record Store Guy, who to some might seem relentlessly expository and dogmatic in their views of good and true music but who I understood to be wise in both their knowledge of music and how it relates to history.

Naturally, my first destination on my recent journey through frequented shops of my youth, was the one in which I’d gone seeking a job. Though it’s existed for over four decades and recently celebrated its 45th holiday season**,** I first came upon Pat’s Endangered Species—The Last Record Store on Earth, in 2012, when I was living in the women’s boarding house just a few blocks away.

The Friday before New Years I find myself sloshing through the sidewalks of Delaware on a gray, drizzly afternoon. I decided to walk the route I would’ve some ten years ago to get to Endangered Species and parked around the corner from the women’s boarding house. The three story home framed by inviting plants and trees now looked like a neutral if not entirely benevolent structure. Just as I was noting that despite my brevity in living the city, Delaware is the most memorable as it is the most unchanged, I happened upon Endangered Species sitting on a different street than I remembered.

The store was two, maybe three times the size of the space I used to frequent. Taking in the new setting, I caught sight of the top of owner Pat Bailey’s head above stacks of records where he was sifting through vinyls, and writing, fulfilling I assumed, some of his behind the scenes Record Store Guy duties such as pricing albums and recording inventory.

Despite the cold weather outside, I became warm, flushed with nervousness. I hadn’t seen or talked to him in many years. I circled the store, resolving to buy belated Christmas presents for my friends back in New York before summoning the courage to approach Pat. As I flipped through Dolly Parton and Kris Kristofferson records, I felt transported back to Endangered Species’ former location where I carefully combed through each piece of inventory, lest I miss something important. Had I ever left empty handed? Sonic Youth’s Kool Thing, Desire by Bob Dylan, that one Twenty One Pilots album (I was eighteen and in deep suffering). I searched around for over an hour, and remembered how on one of my first visits at the old location Pat had commended the time I spent looking compared to other customers.

I finally approached the counter where Pat stood, clutching a light load of CDs, 45s, DVDs and vinyl. Heat rushed to my cheeks again and instead of the thirty-year-old woman, visiting the store for a reported essay, I felt like the nineteen-year-old who had once nervously walked up to the counter doing a busy rush to ask for a job.

“Hi, you’re Pat right?”

“Yes,” he responded calmly. “I remember you.”

“You do?”

“Of course I remember you.”

I felt like the world’s biggest jerk. He had not changed, in his black framed glasses, shoulder-length gray hair and welcoming confidence. He rang me up for an astounding grand total of $13.75.

I had intended to appear relaxed, asking for a casual conversation but instead felt unprepared as I searched for the voice recorder app on my phone as I explained the concept of the piece I was writing.

My late coming to Endangered Species is not an uncommon experience as people are prone to assuming that local music and its stores exclusively exist in the confines of Columbus city limits. “And when they figure it out, they’re like amazed,” Pat said.

While we talk, I maneuver out of the way of customers, waiting to finalize their purchases or ask inquiries about inventory. As Pat explains to me how CDs are actually often a better buy than vinyls since they’re cheaper and more durable, a few teenagers approach the counter.

“Here’s what you should do,” Pat prompts, “Ask this young person why they’re buying a CD and not a record.”

The teen explains telling me, “I find CDs tend to be a better bang for your buck.”

I had experienced the inverse at their age. Finding that collecting second-hand records of sixties and seventies music saved me money but this was just before the resurgence of the vinyl industry which led to bigger artists following suit. It was surprising, seeing stars like Taylor Swift in the stacks of records. I noticed in general, there were brand-new vinyls than I previously recalled.

The tide shifts gradually, Pat explained that CDs might again make a bigger comeback as theyouth purchases point towards but there have always been and will always be collecting records. Things change but they also often remain in similar veins, he told me and I agreed noting how consistent Delaware is.

Pat agreed. “Sometimes you see someone every week and then they disappear out of nowhere.” And then one day you see them again.

*

After I departed Endangered Species, I drove to the complex where I spent most of my childhood. Rounding the corner to the apartment from which my mother and I were evicted, leading to our eventual boarding in the women’s home, I waited for some emotional resolution to hit me. There were no waves of nostalgia or grief, only slight annoyance that the complex was significantly nicer than it used to be. I wondered if they still accepted Section 8.

I stopped collecting records and CDs with frequency when I moved to New York City for college. After I had sex for the first time at twenty in the basement of a record store with a Record Store Guy thirteen years my senior and the ensuing not-quite-romance faltered, the hobby became less comforting. And worse, his store was one of the few I’d found with decent prices in the city. When my Crosley player died suddenly my sophomore year of college I accepted the sign from the universe that though buying vinyls had once brought me much joy that it was no longer sustainable. I tucked it away with other pastimes that I initially deemed as financially unfeasible in New York, like seeing concerts every week and going to the movies.

Record collecting was a bygone era of my life, but during my excursion at Endangered Species I was not simply struck by memories of my younger self. I was inundated with the realization that I still loved the act of reading the track list on an album, seeking a title I knew. Or picking up a record, previously unknown, by an artist I consider myself familiar with. Now, I had the added dimension of shopping for my friends, most of whom had never spent time in Ohio. What album covers would speak to me on their behalf?

*

The next day I stopped by a store that I haunted when I was eighteen and nineteen but didn’t particularly enjoy. Magnolia Thunderpussy has the advantage of being in the (allegedly trendy) Short North, on North High, a street that you can drive north as it turns into route 23. Growing up, I relished driving all the way down from Delaware county to the Short North, watching as my suburb with its shades of rural characteristics gave way to the modest metropolis.

Magnolia was regularly mentioned on now defunct WWCD Radio, the station I tuned in for indie and alternative music and concert announcements. Sitting right next to the popular bar and venue, Skully’s, and a seeming staple within local music sectors, the store appeared likely to become a favorite. When I finally went, Magnolia appeared more like a novelty shop with records. Which isn’t to say that it’s collection of music wasn’t plentiful but it was overpriced. Instead of older people behind the counter, eager to shepherd my developing music taste, I encountered men in their mid-twenties either flirting with my friends or ignoring us. Still, there were select items I knew with certainty I could find at Magnolia new, rather than hoping to stumble upon a cheaper used option. I went when I was willing to spend and confident that I would obtain what I sought after.

Visiting Magnolia as an adult I was less irked by its hokiness—a charge that was maybe always unfair. What record store did I know of that wasn’t selling tie-dye bags and Dark Side of the Moon tapestries? Perhaps what I was then recoiling from was the overselling of its primacy and eighteen was a ripe age for deeming places overrated. When I recently ventured into Magnolia I was greeted cheerfully by two women working. The large store was full of inventory items—CDs at the front alongside a wall of Tshirts, prints and other memorabilia and in the back were vinyls, forty-fives and more band shirts. An older man, who I assumed was the owner, busied about, adjusting records and saying hello to regulars. Yet try as I did, I couldn’t muster up a connection to Magnolia. The prices were still high especially compared to the previous day’s deals found at Endangered Species. Perhaps it was the EDM pulsating at 11 AM but it still felt off. After 10 minutes or so I thanked the girls at the counter and left.

My next and final destination was also on High Street, just a few minutes north into the neighborhood of Clintonville. Though my first purchased vinyl, red limited edition of Sticky Fingers record, was from a Hot Topic, Lost Weekend Records was the first record store where I acquired a vinyl. My mom had taken me there in my quest to find Carole King’s Tapestry. It wasn’t in stock at the time, except for a rare, expensive copy. The owner had taken the costly version down from a shelf, prompting me to hold the vinyl that weighed heavier than most records.

Instead, I’d purchased The Kinks Soap Opera, intrigued by the two disembodied hands on its cover against a cloud filled blue sky but not knowing anything about the record or band. The lyrics revealed a concept album about a famous musician who takes up the mundane life of a man who works a nine-to-five and lives an ordinary, bleak life. I found a recording of the teleplay, Starmaker, on YouTube and watched, fascinated by the seventies theatricals. It was at Lost Weekend that I first developed the habit of buying albums based on intriguing album art, a practice that only steered me wrong once when I bought Jefferson Starship’s Winds of Change.

Though Lost Weekend is a fraction of the size of Magnolia or Endangered Species, it’s packed with items, neatly arranged. During this trip, I noticed Hum’s You’d Prefer An Astronaut on a shelf, high on the wall indicating its loftier price ($80). After first hearing “Stars” on the radio in middle school, it had taken me hours of searching on Google and YouTube to find the band behind the song. It had felt like divine bequeathment when I happened upon a used CD of Astronaut at Lost Weekend, a few months later.

Sifting through the recently arrived and used section, I underwent a similar moment of magical thinkingwhen I saw the three-quarter profile of Gloria Swanson, poised in graceful defiance as Norma Desmond. The album was a recording of Sunset Boulevard film score, performed by the National Philharmonic and a perfect gift for my friend Seven who often cited the movie and Swanson’s legendary character as inspiration. Though I wasn’t specifically seeking a present for him, it sensed I had arrived at the store at the moment precisely to uncover the vinyl for him.

Checking out at the counter, the Record Store Guy accessed my purchases which now included a Springsteen forty-five for my east coast native friends and Guilty by Howard Roberts for my boyfriend, which sports a charming cover of a faux newspaper article about the jazz guitarist. Kind of all over the place, he said and nodded, approvingly mentioning what a good record Guilty is. Not yet immune to such praise, I smiled before admitting that I actually never heard of Howard Roberts,

*

Two days before the year turned over into 2025, and a day before I flew back to NYC I mailed the records, CDs, and DVDs I had accumulated during my Columbus record store expedition to the receptive recipients. There were many stores left unvisited—Used Kids, Spoonful, Elizabeth’s, Roots to name a few. Some had cropped up over the years since I moved away from Ohio, others like Used Kids, orbited in my periphery but for reasons, likely unimportant I had never cultivated a relationship to.

I wrote accompanying letters for each package, hoping to transport not just their gifts but one of the remaining pieces of Ohio and my Midwest sensibilities that I continued to recognize. I couldn’t remember which exit to take to visit my aunt’s house and I drove slower than I walked through grocery stores. Yet somehow, I could still intuit where to unearth the perfect record resonating for the moment.

Driving away from the post office back to my rental I realized that in all these visits, I hadn’t bought a single item for myself.

Madison Jamar is a writer living in New York City. Her essays have appeared in Angel Food, Black Lipstick, Catapult, and more. She knows that Palestine will be free within our lifetime.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal