Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: A Christmas Song for People Who Don't Do Happy Endings

by Amy Carlson Gustafson

I am not a Hallmark-type of Christmas person. Happy endings? Forget ‘em. Give my heart something to ache for. Make my soul melt and harden – just don’t make it swell. Growing up, my mom played lots of Andy Williams while she made an ungodly number of cookies, decorated the tree, and wrapped presents so pretty you felt bad ripping them open. She glowed during the season, especially when surrounded by family and friends. I always enjoyed these get-togethers and her Christmas cheer (I’m not a complete monster). But the seasonal songs I was drawn to had nothing to do with silent nights, kissing Santa Claus, or Rudolph.

The happiest Christmas song I truly love is “Merry Christmas from the Family,” Robert Earl Keen’s tune about a dysfunctional family, which Keen has called the “Rocky Horror Picture Show of Christmas songs.” They drink a lot, smoke cigarettes, deal with Christmas light electrical issues, and make a store run for tampons. If the song had movie kin, it would be a lower-class version of the Griswolds.

I can’t resist the Pogues’ “Fairytale of New York.” Now, that’s just tragedy song porn. From the opening piano chords, I can literally feel my chest sink. Then rise when it turns into an Irish jig and Kirsty MacColl jumps in to liven things up. When Shane MacGowan wistfully sings, “I could have been someone,” with MacColl replying, “Well, so could anyone,” I’m committed to at least five more consecutive listens.

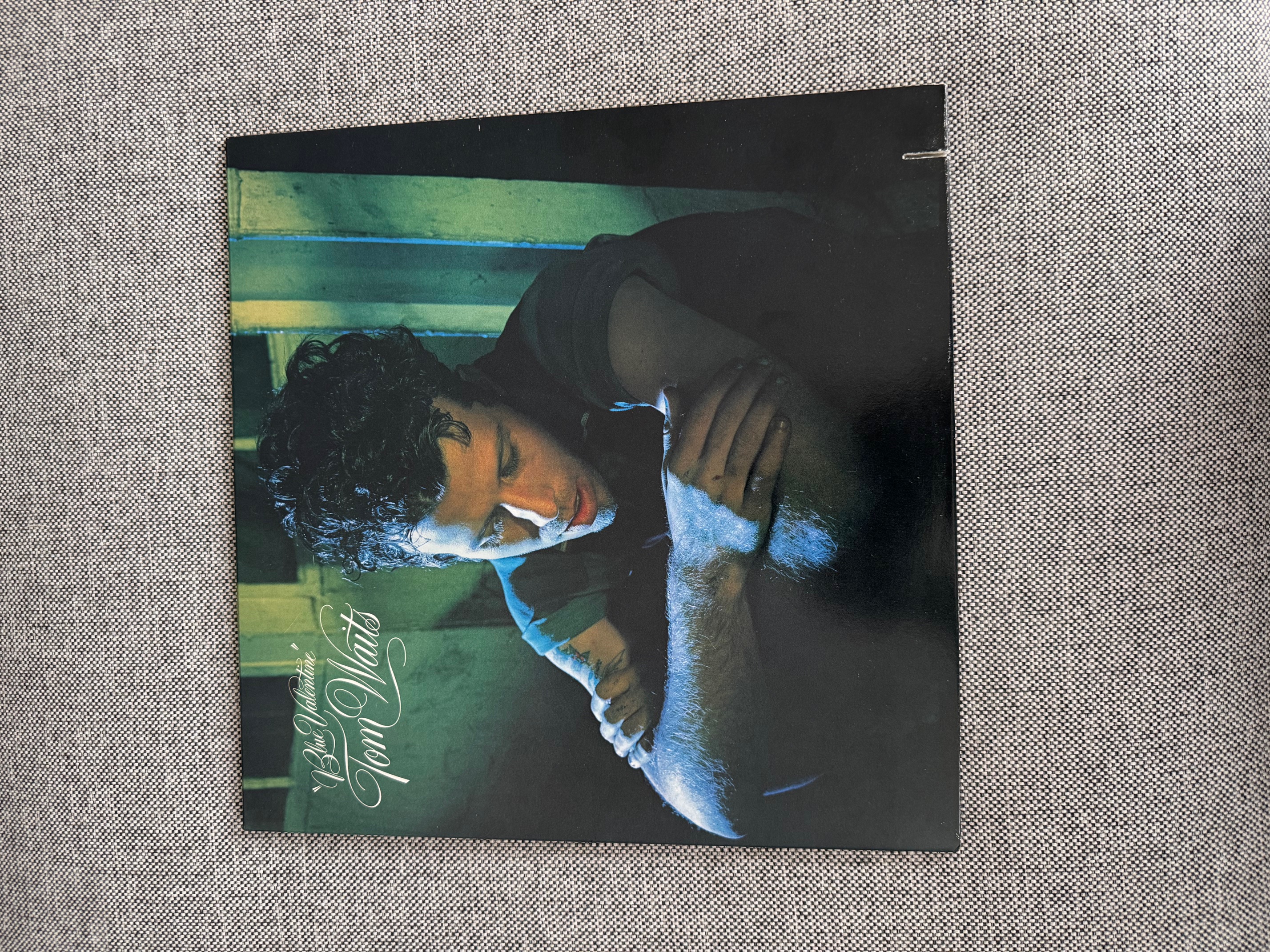

But my all-time favorite song for the season cuts even deeper. Tom Waits’ “Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis” off the 1978 album “Blue Valentine.” Tom Waits is a master at crafting complex characters. He certainly loves his twists and turns, and this one is no different. Whatever he’s saying, It’s best to take it all with a box of salt.

He gives a bit of the mystery away in the title, letting us know the narrator is a woman, a hooker, living in Minneapolis. But he automatically elevates her, giving her a dose of humanity by having her send a Christmas card. She’s not totally alone, right? She has someone she thinks enough about to buy a stamp and a card and take it to the mailbox. That’s not nothing. Also, we know Minneapolis is cold in December, so we all really hope she’s wearing a warm coat.

Set to a jazzy piano melody that oozes dim barroom vibes, we learn the card is for her buddy Charlie, somebody who wears so much grease in his hair that passing a filling station makes her think of him. She’s living on top of a dirty bookstore and has stopped doing dope and alcohol.

Ok – so we have a recovering addict living in an unsavory part of town. But hey! Good news, she’s got a new husband who’s in a band (cool) and has a job (excellent). He’s given her his mother’s ring (aww), will raise her baby even though it’s not biologically his (stand-up fellow), and they go dancing on the weekend (fun!).

I mean, this sounds extremely promising, right? Like, she’s getting back on her feet, feeling better about life.

But if everything’s so good, why does she feel the need to write to Charlie? Reminisce about a shared love of a Little Anthony and the Imperials’ record? Oh, and now she’s admitting that someone stole her record player. That’s a bummer.

She starts to fill Charlie in on the rough stuff she’s gone through. After Mario, who I assume Charlie is familiar with, gets “busted,” she moves back to Omaha to live with her “folks.” Uff da. Her acquaintances in Nebraska are all “either dead or in prison,” that’s why she returned to Minneapolis. It’s grim, people. We are really starting to get into the shit.

She achingly tells Charlie she’s finally “happy for the first time since my accident.” If she had all the money they spent on drugs back, she’d buy a used car lot so that she could “drive a different car every day of the week.” A poignant dream. She’s not talking about unlimited amounts of money or a mansion. She wants the freedom to choose.

We never find out what the casually dropped “accident” was, or how she knows Mario, or why he got busted. We’re left wondering what the relationship is between Charlie and her. Is he a former lover? A brother? A friend? A former drug dealer? A pimp?

Waits delivers the gut punch in the final four lines. She spills the grim truth. There’s no husband who plays trombone, she needs money for a lawyer, she’s in jail, “eligible for parole come Valentine’s Day.” She’s desperate.

Waits leaves us with a little sliver of hope. She’ll be up for parole soon, she has dreams of the life she’d like to have, and she still has Charlie to reach out to. And maybe thanks to the Christmas spirit, Charlie will pay for a lawyer if he’s able. Is she worth betting on? I guess that’s for Charlie to decide. I hope he does.

Maybe I do like happy endings after all, or at least the possibility of them.

Amy Carlson Gustafson is an award-winning journalist who writes about anything that tickles her fancy. She started her career as a music critic before becoming a pop culture and arts reporter. After a long detour, she’s dipping her toes back into music writing, and the water’s warm.