Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

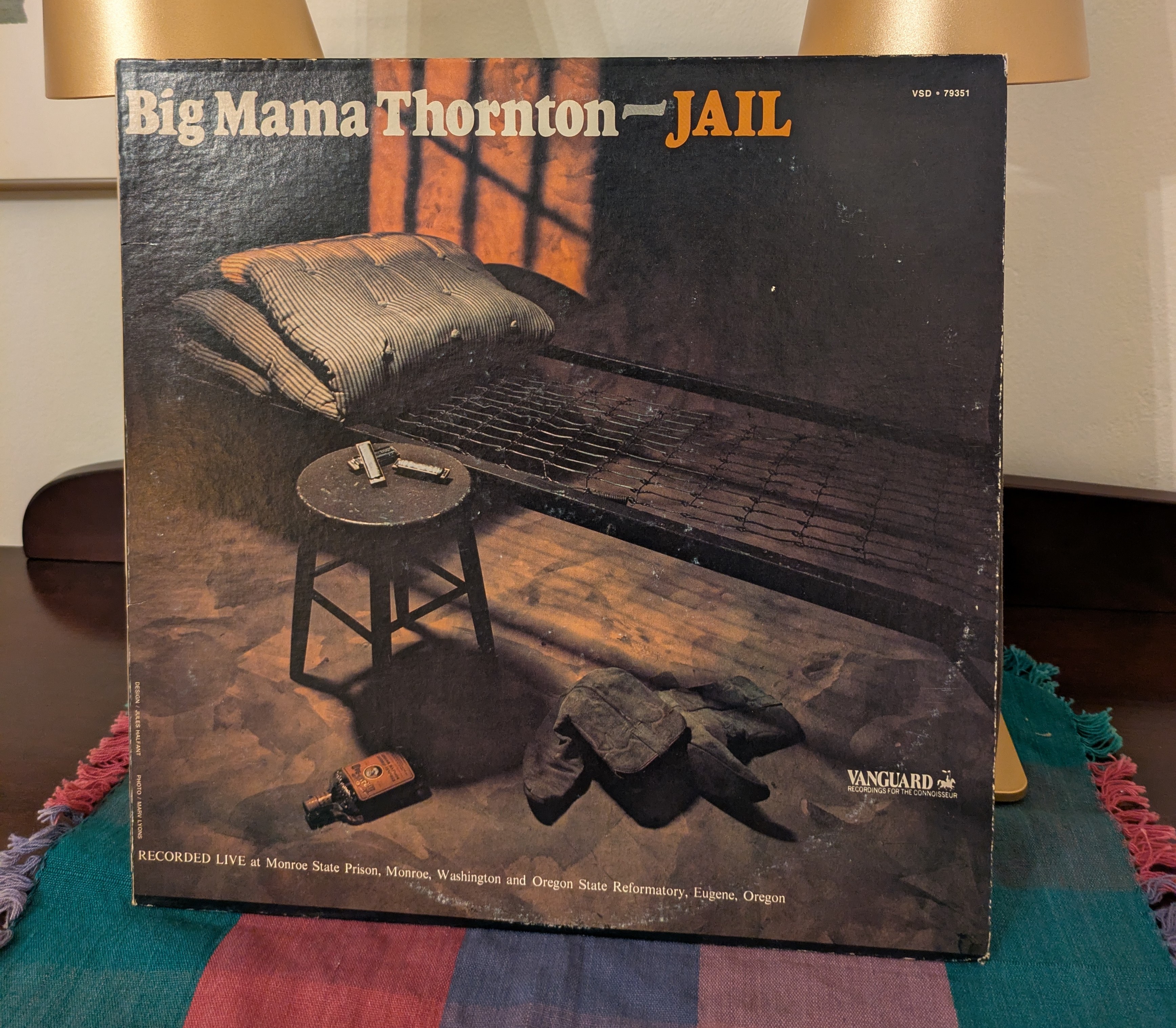

Featured Essay: Big Mama Thornton's "Jail"

by Tim Foley

A few months before Big Mama Thornton’s untimely death, I was speaking on the phone to an assistant public defender in Los Angeles. She met the blues legend at a fund raiser for an anti-poverty group, and was stunned by how frail and small Big Mama looked. Neither of us were knowledgeable regarding what the singer should look like – Big Mama, hardly a frequent presence on television, was no longer touring and YouTube didn’t exist – but we assumed, of course, that the woman would be, well, big. “She’s a peanut,” my friend said, and we laughed.

We didn’t know that Big Mama had shed hundreds of pounds, that her health was terrible, that years of life on the road and drinking to excess had decimated her liver and kidneys, that her lack of financial resources limited the scope of medical care, that she would soon die, virtually penniless, in Los Angeles during the summer of 1984. She was only in her 50’s, but looked decades older. One could be forgiven for not knowing about her difficulties because she hardly ever complained. In interviews, she would stress how fortunate she was, how wonderful the opportunities that enabled her to sing, how talented and generous were the musicians she performed with. Willie Mae Thornton left home at 14 to sing in a band and spent the next forty years doing exactly what she loved, living a life rich in experience, if not monetary compensation.

Looking back, one might think that the music business did not treat her well, and that she made some bad choices. Despite an obvious vocal talent, an original, compelling voice, and a charismatic stage presence, she never had the breakthrough that many thought she deserved. The royalties, both from her records and her songwriting, were channeled elsewhere. She never organized and led her own band, instead playing with great musicians who worked mainly for somebody else. She signed with little-known, distribution-handicapped labels. She seems to have been mismanaged by those around her, and money was always tight. But here’s the thing: until the end, she performed relentlessly, singing in every kind of venue across two continents. She sang with Johnny Ace and Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King. She shared stages with all the great blues legends. She toured Europe multiple times, introducing audiences to a distinctly American artform. She made a living singing, and, because she did, she felt blessed.

Big Mama was far more comfortable on stage than in a recording studio. The records were few during her prime, singles recorded sporadically, mostly issued on obscure labels. Her biggest hit was “Hound Dog” (1952), a Leiber-Stoller composition written especially for her evocative, powerful style, and the legendary songwriting duo’s first major hit, a number 1 on the R&B charts. A few years later, her version was eclipsed by Elvis. Her most famous composition was “Ball and Chain” (1961), AKA “Ball ‘N’ Chain”, her own version also eclipsed (and imitated) by Janis Joplin, who decided to record it after watching Big Mama tear through the number in a San Francisco nightclub. Late in her career, Mercury put out a full album, “Stronger than Dirt” (1969), a collection of classic blues, updating many of the songs she had first performed years before. Then came a favorite disk, the album “Saved” (1971), on the little known Pentagram label, a gathering of traditional gospel standards that she made her own.

In 1975, Big Mama was in decline, the voice holding less power, and her medical issues growing, but jazz label Vanguard picked her up and released a collection, some of her last studio recordings, entitled “Sassy Mama.” A few months later, she put on two shows for prisoners in the northwest, the first at Monroe State Prison in Washington and the second at the Oregon State Reformatory. In the spirit of Johnny Cash and his own recorded prison shows, Vanguard released “Jail,” a sampling of the two concerts. The album is a small, beautiful, timeless gem.

The production of the album is a bit tinny and lacks a deep low-end, but the sound is clean and the solos crisp. The band is a group of pros: George Smith on harmonica, Bill Potter on sax, James Nichols on piano, Edward Huston and Steve Wachsman on guitars, with Bruce Sieverson on bass and Todd Nelson on drums. The band swings, with an improvisational edge, and Big Mama carries the vocals with her characteristic poise and sass.

The show starts with a spirited introduction, and the band launches into “Little Red Rooster,” a rolling song different from the Howlin’ Wolf classic, writing credit on this one to Big Mama. Other tracks include her signature songs, “Hound Dog” and “Ball and Chain,” a groove-driven version of “Rock Me Baby,” and the folky “Sheriff O.E. & Me.” The title track “Jail” is a classic slow blues, anchored by this solid group of bluesmen, with Big Mama’s voice embodying both the frustration and the fortitude of the lonely inmate. The last track is a jam of the gospel number “Oh Happy Day,” reminding us that Big Mama’s father was a preacher, her affection for the traditional church numbers shining through, though the song fades out far too soon, something that can be said about Big Mama herself.

Tim Foley is a writer and playwright, currently living in Sacramento. His collection of ghost stories, Tales Nocturnal, was issued by PS Publishing in 2025. Long ago, he played guitar for a few Bay Area bands and, even longer ago, he was the music director of an FM radio station. His website: **www.TimothyJFoley.com

Previously by Tim Foley:

[Nova Mob - Last Days of Pompeii] (https://ihavethatonvinyl.com/essays/nova-mob-the-last-days-of-pompeii-rough-trade-1991/)