Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

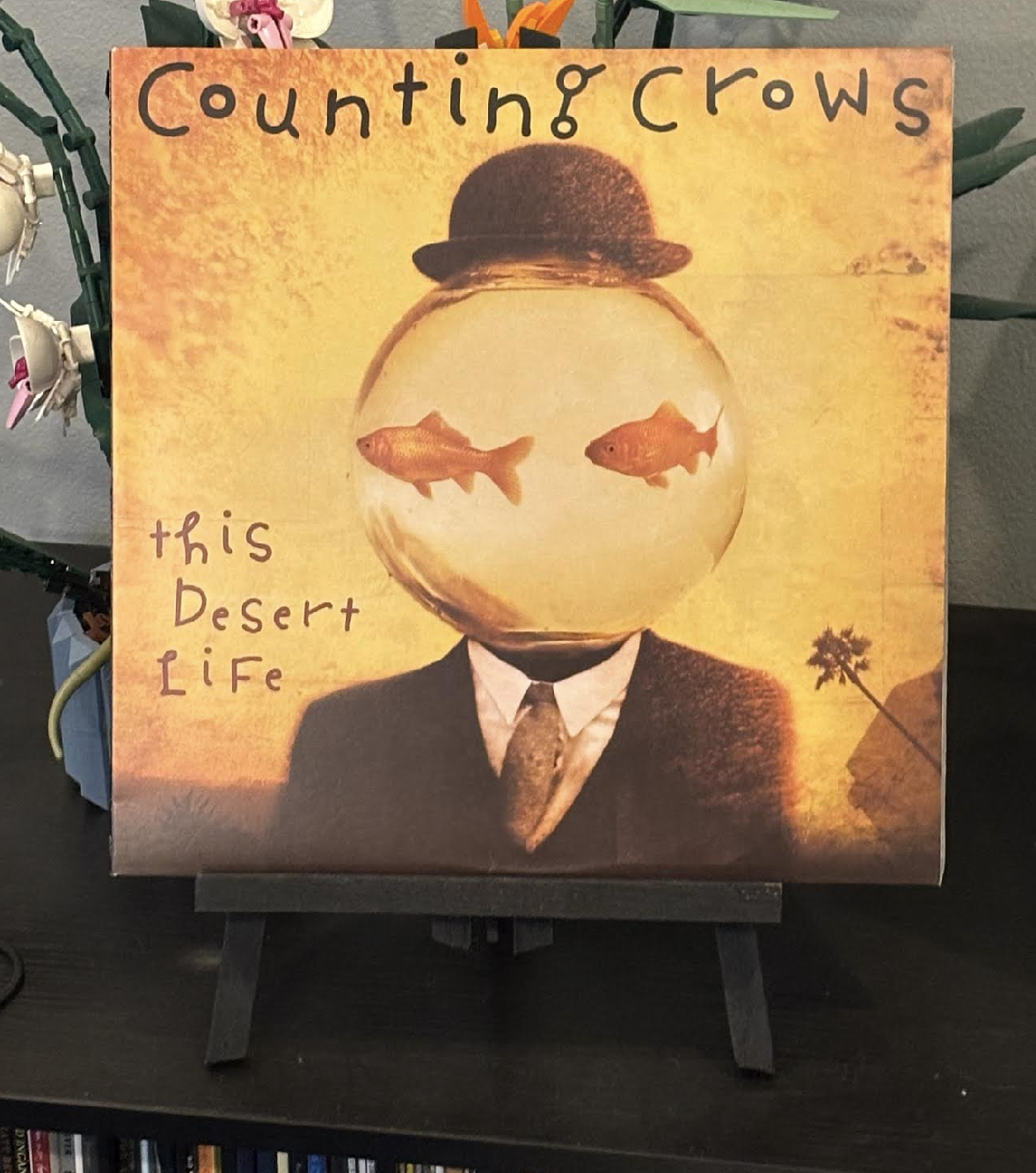

Featured Essay: Four Days: Searching For This Desert Life

by Travis Cook

May 2011

I am sitting in the living room of my childhood home. Outside, I can hear the cows gently mooing away in the night. My father is asleep in his room next to the living room – he snores so loudly that no amount of noise will wake him. Upstairs, my mom lies in her bed, slowly dying from breast cancer.

I can’t sleep. I’m working two jobs, trying to save up enough money to move out of small-town Ohio, move somewhere that I can try and make something of myself. But I’m paralyzed. My mother is dying, my father isn’t speaking to me, and I’m stranded in the middle of Ohio.

I kill time as any introverted depressive should by frequenting the local library. I pour through book after book and catch up on esoteric foreign films. On a whim, I grab a DVD of the best SNL music performances from 1991 through 1995, thinking I’ll enjoy the performances by Nirvana, Paul McCartney, and R.E.M. I do, but something else happens.

Midway through the video, one of the former cast members introduces the Counting Crows. I’m only vaguely familiar with them as the band that wrote that Shrek song, as well as the writers of “Mr. Jones”. I figure this is a chance to catch up on my reading while I wait for the next act I know.

And then I hear the lyrics:

Step out the front door like a ghost into the fog Where no one notices the contrast of white on white And in between the moon and you The angels get a better view Of the crumbling difference between wrong and right.

Well, I walk in the air between the rain Through myself and back again Where? I don’t know. Maria says she’s dying Through the door, I hear her crying Why? I don’t know.

‘Round here, we always stand up straight ‘Round here, something radiates.

I’d spent most of my life to that point wondering if any band will ever really speak to me. I’ve heard rumors before of music changing people’s lives, of finding commiserate truths and profundities in song lyrics, but I always figured that was hyperbole at its finest. But in the dark hours in my living room, lost and alone, I see a shy, introspective man giving voice to the sad longings within my heart, lost, broken, confused, and alone. And yet, round here, we always stand up straight.

Something radiates, and I fall in love.

October 2011

I am driving across America, and I have begun an obsessive pursuit of all of the recorded works of Counting Crows. My mother is still dying slowly in Ohio, my father is still estranged from me, none of us knowing exactly what to say to one another as our world crumbles. I have saved $2000 in cash, more than enough for a security deposit and a month’s rent of a studio apartment in Chicago. The only issue is that I need to be in Chicago to try and rent an apartment in Chicago. Thus, I drive back and forth between Ohio and Chicago, continually seeking out a new home.

As I drive, I pump CD after CD into the car, pursuing my scholarship of the works of Adam Duritz. I’ve memorized the lyrics to everything on August and Everything After, and have a deep appreciation for the deeper cuts of Recovering the Satellites. I even come to love “Accidentally in Love”, that Shrek song, on its own merits, unironically. My favorite, though, is This Desert Life, which gets the most mileage in my Midwestern crossings.

As I drive through the cold Indiana nights, passing a long windmill farm on I-65 as I head south, “Four Days” and “Mrs. Potter’s Lullaby” echo through my car and across the plains. The windmills blink red safety lights in the darkness in time to “Amy Hit The Atmosphere”. The most personal and lovely song is “Speedway”, a song about needing to break out of a rut, break out of a stale, toxic life, out into nothing. For every dark mile of Indiana, the barrier between me and a new life in the city, “Speedway” is probably heard at least once, a ghostly transponder from a radio without buttons or dials.

I don’t know what I’m doing with my life, but I need to do something. I don’t know what I need, but the music helps. The music helps so much. The music saves my life. Anytime I think that there’s no point in continuing, that it might be easier to just veer off the side of the road and descend into oblivion in a ditch, the next track comes on. I think about getting out, just trying to get myself some gravity. So I drive onward, a silver glimmer in the night, thinking about breaking myself.

June 2013

My mother has been dead now for almost a year and a half. I don’t know how to grieve – nobody does the first time you lose the most important person in your life. You just learn in the moment the best you can, go from there, and wait for the pain to fade.

I’ve come back to the farm for the summer, working on contract for a small theatre company in Dayton. It pays next to nothing, so I’m working for my father on the farm. We’re speaking more than we used to, but we clash anytime there’s a difference of opinion in how to run things on the farm. Nevertheless, the pay and the hours are good, and it takes my mind off of more unpleasant things.

Until it doesn’t. One morning, he finds me at work in the chicken house and tells me that we need to load up some junk to take into town. Without a word, I follow him back to the farmhouse, where he begins unloading my mother’s items into the back of the truck.

“You’re getting rid of her things,” I say, too stunned to push back.

He turns to me, his face screwed up in anger. “This is how it’s gotta be!” he yells, understanding immediately my hesitation but lacking any way to empathize or relate. When my grandmother – his mother – died, all of her things wound up in a storage locker. When my mother died, the memory was too painful for him – he systematically began removing every trace of her from the house. Her collection of fridge magnets. A cluster of stuffed animals. Clothes and prized possessions from her room. Soon, there is almost no record of my mother’s existence on the farm. Only her records, which I’ve stashed away in my room, hidden from prying eyes. Mostly beat-up and weathered classic rock, but it’s something.

I go along with this. The one time I pushed back, I was met with a gruff “this is my house”, the sort of thing you’d expect from a Midwestern farmer.

In the evening, I burst out of the farm post-dinner, heading to Dayton. On a whim, I stop in the small record shop in the bohemian district, figuring to while away my time there. I aimlessly drift among the shelves, looking for nothing in particular. I always make a point to search the ‘C’ racks, in case an unlikely Counting Crows vinyl is there. There usually aren’t.

Until there is. I can scarcely believe my luck – August and Everything After, reprint, double vinyl edition. I don’t even own a record player, but I snatch this up and fork over my day’s earnings. At last – my first Counting Crows vinyl. Not a piece of my mother, for that is gone, leaving a gaping hole. Rather, a new piece of myself that begins to fill that space.

May 2024

I get the call from my brother. We’re selling the farm.

Not the whole farm, just a small lot. The land has value, and our cousin needs space to build a new home for his family.

“Chad’s looking for five acres. We have room in the northwest field,” said my brother.

“That’s fine,” I say. “Let me know if I can help.”

“Sure. Oh, dad says you and I can split the money fifty-fifty.” My father has retired and moved south to Florida. We speak once a week, just to check in, shoot the shit, talk about the Reds. He’s content down there in the warm sunshine, and the farm is ours to deal with as we see fit.

“Sounds good. Keep me posted.”

I don’t think anything about this for several months until May of 2024, when my share comes in the mail.

Or, as I find out, the first half of my share. For tax reasons, my brother is sending my portions in chunks, to maximize what we both can claim.

Still, a check for half of $25,000 is still a hefty chunk of change. My remaining wedding debts are cleared out. I now have money in my savings to set aside for a new home, retirement, a rainy day, whatever I want.

On the other hand, this is a large amount of spare cash that is absolutely eating a hole in my pocket, screaming at full volume things like “Spend me!”, “Extravagant Purchase!”, “Buy Something SILLY!”

I mention this to my wife. “I say go for it,” she says. “We’re in a good place, we’ve got plenty saved up, we’re not looking to buy a house again for a few years. Buy something Silly!”

I think on it for a bit before it comes to me all at once: This Desert Life on vinyl.

By this point, I’ve collected most every Counting Crows record I can find. Recovering the Satellites has joined August and Everything After, as well as most of their later records. Some, like Hard Candy and Saturday Nights and Sunday Mornings aren’t available on vinyl that I can find. Others are relatively easy to pin down, like their latest EP. However, This Desert Life is the rare gem – released in limited quantities, unable to be remastered after the Universal archives fire in 2008. This record can be found, but only for a Silly amount of money.

Which I now happen to have.

I peruse the Internet, scouring for a copy in quality condition for a “reasonable” price, though reason has taken leave of its senses here. I find it on eBay for just over $1200. As with anything of this nature, my finger hesitates as I hover over the “complete purchase” button.

Is this really what I should do?

I think back to that night on the farm, discovering the true nature of my favorite band. To those long, lonely nights driving back and forth from my old home to my new. To discovering a true record of their music when I needed it most. This isn’t a silly purchase. This is taking a piece of my old home and claiming something new, something that is a part of me, that was forged out of my broken old life, remade and built up stronger than ever. This is a testament to survival, to the record that saved my life.

I click the button. The record arrives four days later.

Travis Cook is a writer, as well as a former/erstwhile musician, actor, director, and general jack of all trades/master of none. He enjoys watching baseball (go Reds), movies, movie trivia at the Music Box Theatre, and spending time with his dog, Mr. Robot. He is a graduate of BGSU and is currently workings towards a Masters in Writing at DePaul University. He and his wife live in Chicago.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal. Tips go toward paying writers, an editor and for site maintenance, You can also join the Patreon.