Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Jazz as a Working Metaphor for Life

by Charlee Remitz

Like most endings, my grandfather’s death ushered in a new dawn—the era of jazz. It was April of 2020 when his Alzheimer’s became too unmanageable for my small grandmother and their Florida house to contain. He forgot how to catch himself when he fell, and his body became black and blue. I’ve decided, in all my amateur field work, Alzheimer’s is many things, but the very worst of them is the complete departure of one’s motor function. It was not the instability—we can all withstand a fall—it was knowing to throw your arms out before the whole hulking mass of you hit the floor. To tuck your head and do it with a shred of grace.

The family, like a small tribe on a wintry planet bracing itself for a time without sun, descended into chaos when our patriarch forgot how to golf—the most observed of his hobbies. We picked over his diet, sharing Internet search inquiries and intuition, like some of us had more insight into the dilemma simply because we felt something to be true. There was so much sensation. So much open grief. We wished it could be so simple as to take away sugars, to serve him meals slightly resemblant of bird food. But there was no keeping him alive, no anchoring him to the present. There was no willing his disease away. It was a realization humans would suffer again and again: that life ends, and at no point does it become as putative as one’s need to sleep.

We couldn’t keep involving ourselves in a fight that wasn’t ours. And no matter what can be said about the final stages of Alzheimer’s, I still feel there’s a certain spiritual presence lording over the host, and perhaps that’s who we bowed to in the end. He was done—we were no longer in denial of that fact—and so were we.

We moved him into a memory care unit in Montana, outfitting his small apartment there with furniture that came as a part of a set. It was strange, not unlike a parent furnishing their child’s dorm. We shifted uncomfortably in our new roles around this alien dependent, and when we left, he didn’t leave with us, which was the strangest sensation of all.

When we visited, we had confused, and often distressing, conversations with him through a screened window. At times, he grew so upset that the visits were cut short, the nurses assuring him he knew the masked strangers peering in at him like he was a bird at the zoo. In fact, they were family! The whole enterprise felt like a hell specific to him. He, who had the faces of his grandchildren printed on his skis so he could point to them with his poles when talking about us to random skiers on the chairlift. He, who lived to the tell the tale of the ten thousand misadventures he dragged us on. He was no match for a life of anonymity, for a world without his legacy. And in two months’ time, he took one final, epic and injurious plunge.

In hospice, like a little boat in the eye of the hurricane, he sipped chocolate milkshakes through a straw while my grandmother wet his lips with a sponge at the end of a stick. He had meaningful, soundless conversations with a bright spot in the corner of his room, at times pointing at it with the last of his conviction, his mouth agape or tipped slightly in the direction of a smile. We couldn’t be certain, but in our different estimations of What Comes Next, the family became convinced he could see it. Whatever it was. Wherever it would take him.

He left behind all the usual things: photobooks with the original negatives, clothing, a staggering wealth of Scotty Cameron putters. And for me, a large box of vinyl in different stages of wear and tear. There was no Sinatra or Tony Bennett. No Dean Martin or Bobby Darin. As I fingered through those albums, I felt uniquely rich. Loss was as significant as it was final, and there I was on the floor meeting my grandfather through this corpus of jazz again.

His was no collection to imply a purely selfish interest. There were vocalists—sure—the occasional live album—Etta James in Montreux, numerous recordings from the Blue Note—Bing Crosby’s extensive Christmas catalogue, and compilations done by Playboy. But mostly, there were instrumentalists. Art Blakey, Bill Evans, Miles Davis, Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, Art Tatum, J.J. Johnson. Records meant to be supplementary, when the lights were low, and bottles of Ruinart were free-flowing, every conceivable surface covered in cheeses and food, candles lit on the built-ins as if for a midnight vigil. Here was the legacy of a life spent in service of bringing people together in all the plain and blockbuster ways. Here was my grandfather, as vivid as ever.

My mother and I spent many weeks in Montana standing watch over my grandmother as she received various cakes and flowers and covered platters of foods and visits from her neighbors. We drank wine and played cards on the patio, and I followed the trails through the neighborhood, listening to essays from the New York Times about Val Kilmer and “The Woman Who Might Find Us Another Earth”. And then, when my grandfather’s remains were emptied into a sable urn and we’d flipped through a catalogue, picking out jewelry and crystal balls we could have made with his ashes, my mother and I packed up our car, with our geriatric dog, Aspen, and the box of vinyl in tow, and we drove back to our second-floor Hollywood condo, where we continued to wait out the pandemic.

Only this time, we had jazz.

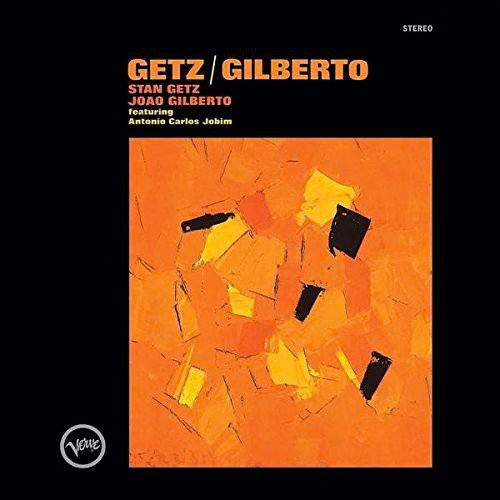

We had Getz/Gilberto with “The Girl from Ipanema”, and when we played it, life felt like a movie. It teemed with possibility. We became mixologists. We learned how to make cilantro margaritas from a Facebook video uploaded by our old country club, watching as they smashed gobs of cilantro into the fresh juices of limes and oranges. We celebrated the tiny yields from my quarantine garden with farm-to-table bruschetta and lined the staircase leading up to our front door with blue bottles and fairy lights. For the first time in a long while, I picked up the guitar, and, with it, I wrote an entire album.

There was absolutely no reason losing the most significant man in my life should set off a time of deeply felt romance, but this was an era of whimsy. Of fresh air pouring into the house at all hours of the day. We were forced to slow down by the pandemic, to find ostensible meaning in doing less, and the jazz only helped to ease the compulsion to speed back up and go as fast as we can.

Losing him felt impossible, but jazz made it possible. Jazz made my grief sparkle, gleam. I may not have sat in his office with him while he pulled out the tumbler of scotch and taught me to savor its sweetness, but I was touched by his elegance. I would always endeavor to be as elegant as he was, and I realized part of this elegance was just an extraordinary and uncanny ability to be spiritually present in the world. He was always there when I spoke to him. And I wanted to be here too.

When Vinicíus de Moraes spoke about the girl from Ipanema, a real Carioca living on Montenegro Street in Rio de Janeiro in the 60s, he called her “golden.” He said she was “full of light and grace, the sight of whom is also sad, in that she carries with her, on her route to the sea, the feeling of youth that fades, of the beauty that is not ours alone—it is a gift of life in its beautiful and melancholic constant ebb and flow.”

And that was just it.

I’ve recognized jazz as a working metaphor for life itself. There is an ebb and flow to the musicians on stage. A certain rhythm that takes some time to settle into. Part of me thinks jazz finds you when you’re ready, that it’s meant for the meditative, for those who’ve found the courage to let their hearts do the leading. It doesn’t seem possible to play something so intuitive otherwise, to compose with your mind busy managing.

By leaving me to sit in thoughtful contemplation with a bunch of dusty records in a box, my grandfather managed, in death, to teach me how to surrender, to let things happen, rather than forcing things to be. It was Thelonious Monk who said, “Where’s jazz going? I don’t know. Maybe it’s going to hell. You can’t make anything go anywhere. It just happens.”

Charlee Remitz is an award-winning singer-songwriter, producer and mixing engineer currently on a mission to see every lighthouse in the U.S.. She delights in sharing her life with the world, keeping her social media up to date with all the whimsy she’s shot on film, and regaling her audience with the misadventures she’s found along the way. Her most recent project, Blue Monkey, is slated to release their debut album, AGELESS, June 6th.

To follow Charlee’s lighthouse journey or hear Blue Monkey’s music, find them on Instagram - @charleeremitz and @bluemonkeypresents