Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Kansas City Jazz and Searching for Records

by Scott O'Kelley

I grew up with records. My earliest memories were the sounds of Kansas City jazz, the warm smell of tubes, and the sight of my dad’s reverent interactions with his albums and hi-fi.

One of the first things he taught me was how to hold a record. And among my first possessions were my own little record player and my own little stack of records: mostly the usual kiddie favorites of the day–The Chipmunks, Captain Kangaroo, assorted Hanna-Barbera albums—along with some of his castoffs. (Wonder if any other kids in my kindergarten class had a 78 of Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog”?)

So loving music, playing records, treasuring the albums—this was always something we shared, despite our musical differences: I was a Beatlemania boomer who’s lived through records, cassettes, 8-tracks, open-reel tapes, CDs, Blu-rays, HDCDs, and endless streaming options. He grew up with depression-era radio and changed formats exactly twice: going from 78s to 33s to CDs.

But we always appreciated each other’s appreciation. And we definitely agreed on owning the music you love. In the old days, that wasn’t always easy: You could only own a record if you (A) bought it new, (B) ran across it used, (C) discovered a reissue (usually expensive and from Europe or Japan), or (D) tracked down a copy through the print-based network of sellers and fellow enthusiasts.

Current radio hits aside, you could only enjoy the music if you had it in your hands. Collecting was, like the format itself, hands-on and all analog. So finding a coveted rarity took legwork, sleuthing, and patience. And my dad loved nothing more than being a vinyl Sherlock.

So I’ll add a fifth possibility: (E), receiving it as a gift.

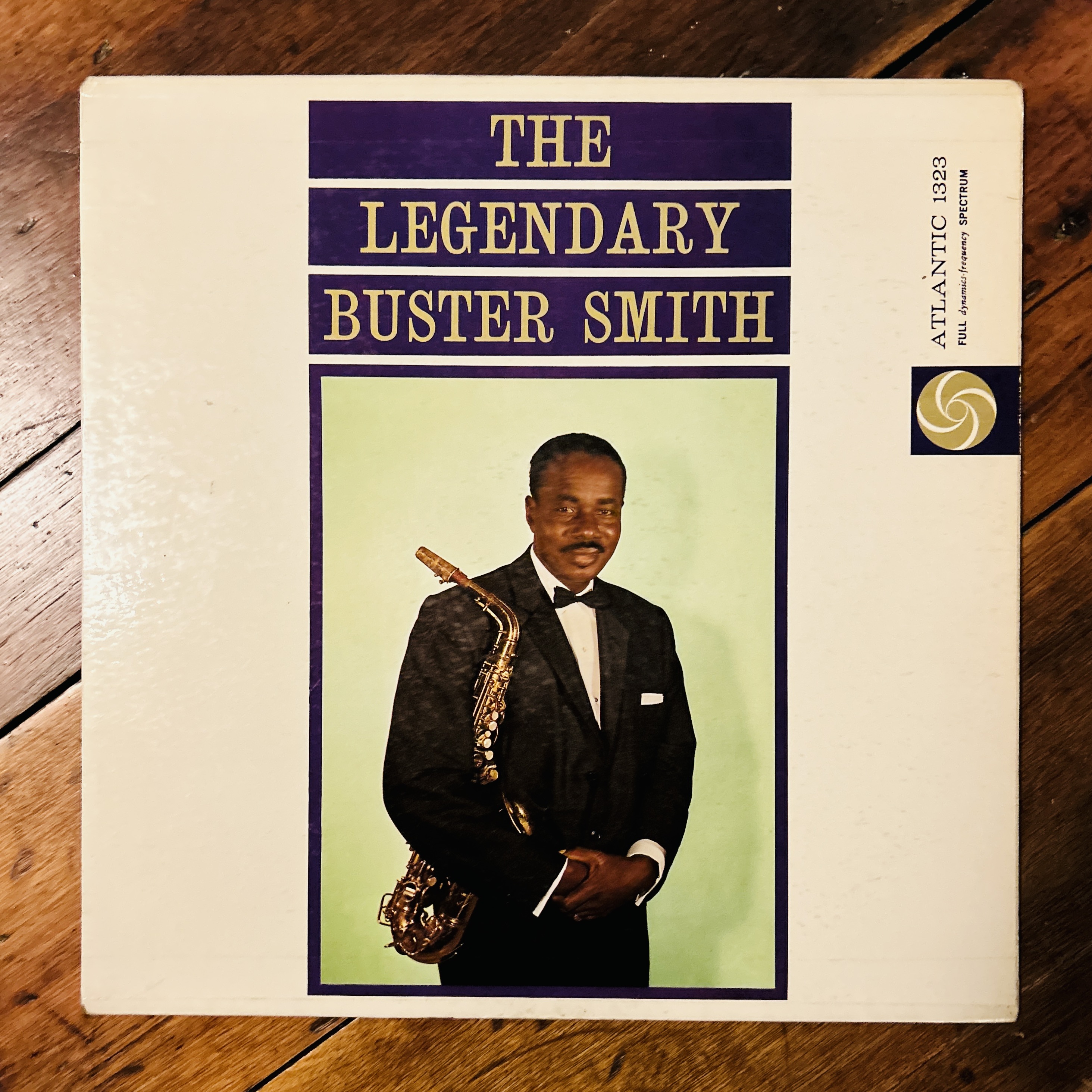

As I mentioned, I grew up with Kaycee jazz, romanticizing the city and its music early on, which fueled a mild fanaticism for Charlie Parker. That—in turn—led to a fevered search for The Legendary Buster Smith (Atlantic 1323).

Known as “Professor,” Henry “Buster” Smith was a Kansas City legend and a throughline in the evolution of jazz, playing medicine shows as a kid, touring with popular swing bands in the ‘20s and ‘30s, and mentoring a young Charles Parker, Jr., on the cusp of bebop.

But despite four decades as a musician, recordings of Smith are scarce. So when Atlantic Records coaxed him into a Fort Worth studio in 1959 to record just his second session as a leader and his first (and only) LP, they were expanding jazz history.

Released in 1960 in both black-label mono and green-label (true) stereo, the album was a genuine missing-link of a disc and long out of print when I heard about it in the ‘80s and started searching.

How did it sound? Back then you usually didn’t know until you put needle to vinyl. According to the October 1960 HiFi/Stereo Review, “The results, while valuable, are not as consistent as they might have been.” Musically middling in other words, despite its cultural significance. But we often collect based on what the performance means as much as how it sounds.

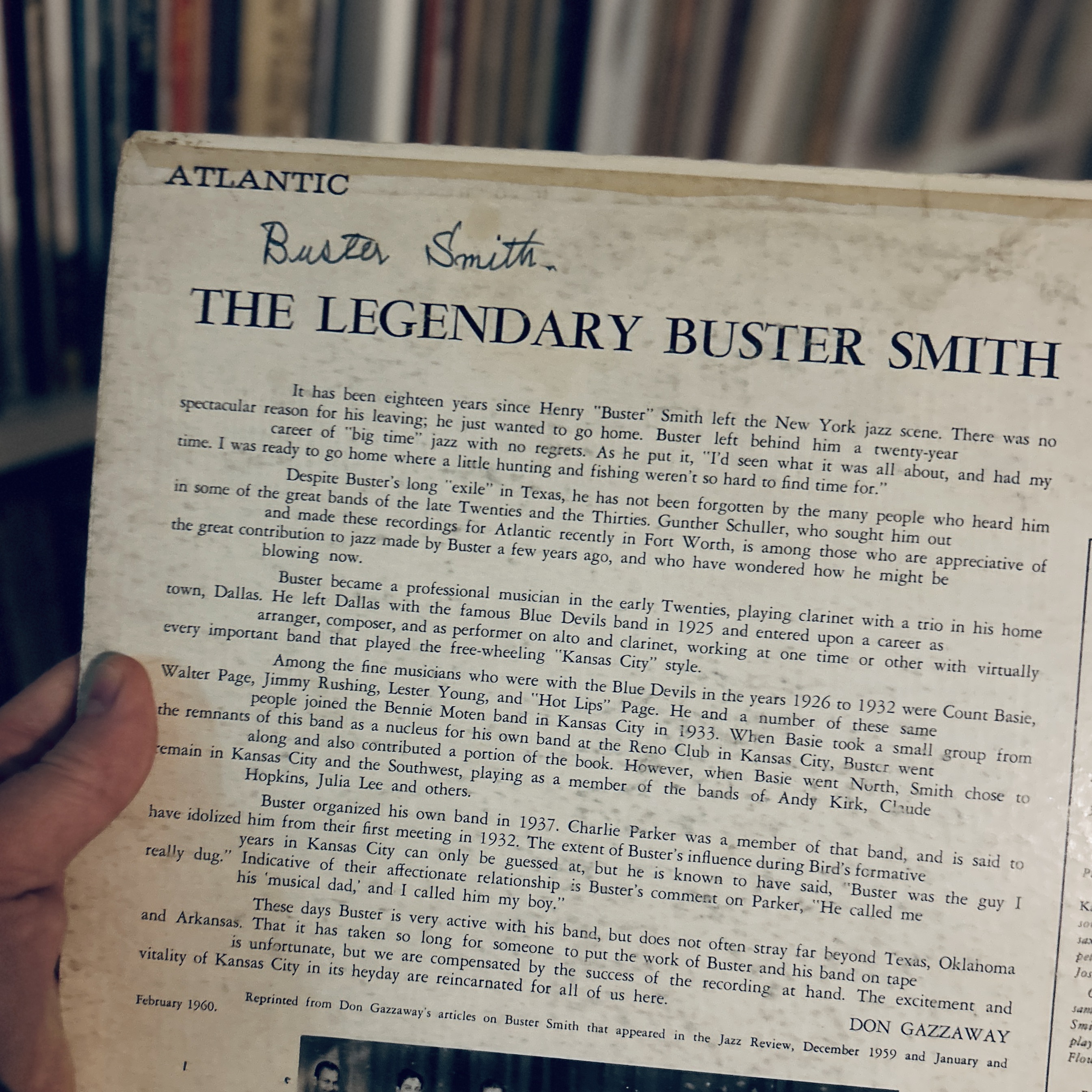

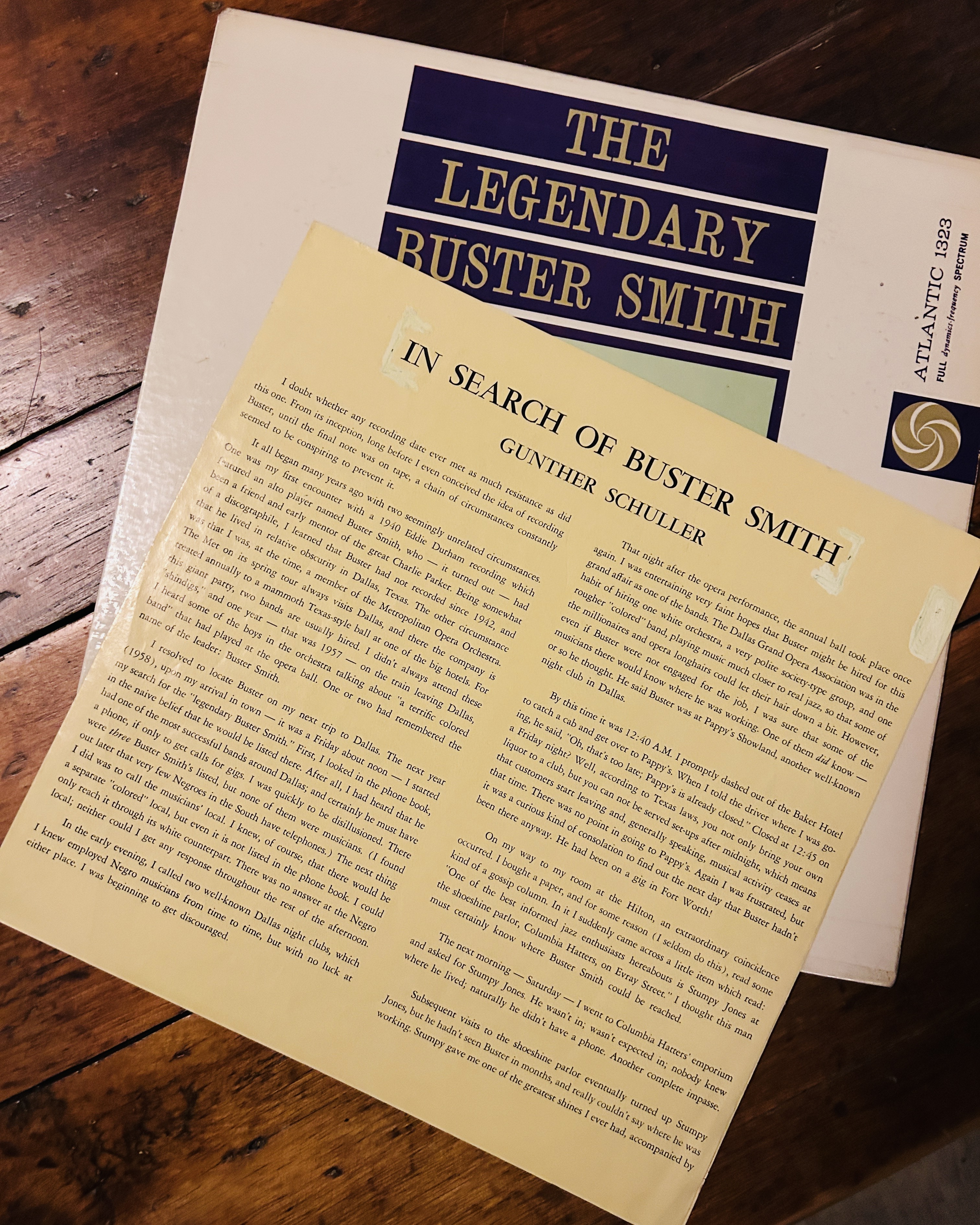

And this record means a lot. Supervised by classical composer and musicologist Gunther Schuller, the recording finds Smith leading a group of local musicians through typical Kaycee jump blues and standards, filtered through late-‘50s R&B sensibilities. “In Search of Buster Smith,” Schuller’s four-page insert that came with the original release, describes the significance of Smith, this session, and the Parker connection in typically bookish liner-note prose. According to that same 1960 review, Schuller “details (with suspense worthy of a detective story) all the frustrations involved in finding Buster and in finally getting his band into a Dallas [sic] recording studio.”

But again, I’d never seen a copy, hadn’t read Schuller’s text, and didn’t even know the song lineup. But I knew The Professor had tutored one of my favorite artists, put his fingerprints on modern jazz, and largely disappeared, so it was a must.

The record when I was searching, but not exactly what most collectors were after in the MTV era. But that also made it the perfect quest for my dad and his pencil-and-paper search algorithms.

Since he came of age with World War II-era swing and jump blues, bebop was “modern jazz” to him and a definite dividing line in his musical tastes. But he knew I loved Charlie Parker and he loved the thrill of the hunt, so I could practically hear the gears churning when I told him about the Buster Smith record I was looking for. I don’t even think I had the catalog number: It was on Atlantic, ‘50s or ‘60s, and that’s about all I knew.

But he found one. Actually two or three; another copy for my friend Ted who’d told me about it in the first place and maybe one for himself. Then there was another: A stereo copy to go with the mono he’d given me originally (or vice versa). And then a few more he picked up here and there.

Since this record was important to me it became important to him.

The man loved music. And he loved collecting (some might say hoarding) the LPs and 78s—and the movie posters and glossies and ads and videos and magazines and assorted ephemera related to the music he loved. An ardent record hunter and gatherer, he got the idea to open a music shop as a retirement gig. That naturally required (or became an excuse for) more hunting and gathering for the store, which—to no one’s surprise—was never more than an idea.

And I don’t think he ever really wanted it to: He was doing something more important than mere collecting: he was saving.

He’d quarried a lode of Glenn Miller 78s and Gene Autry onesheets and Metronome magazines and Ink Spots sheet music and all the other cultural flotsam and jetsam that most folks outside his generation didn’t really care about. And this wasn’t a private archive, but almost a treasure trove for myself and for my friends. The most generous person I ever knew, he loved going on the hunt for my buddies’ holy grails, too.

The next thing he’d always ask—after getting the record info—was Who else would want a copy?

He passed away a few years ago and I hated/loved going through all this stuff—all the things he’d saved—helping my mom get things in order.

I kept a few things—not many. Most was sold to other collectors and the local record store. Some is still in the basement. But even if no one else wanted it, I loved that he did. And I loved going through all the boxes and crates and stacks—like the final scene from Citizen Kane—being part of his stuff. Being with him in a way.

Best of all was the stash of about 50 copies of The Legendary Buster Smith. I literally laughed out loud. A previously unknown and unremarkable record had become a serious decades-long quest. I’ve sold or traded a few, but kept most of them and still love giving them to friends.

He would have loved that, too.

Scotto is a preacher’s kid from Arkansas who moved to Kansas City, went to art school, worked in record stores, was a journalist, then went to grad school, became a therapist, and have been mental health director for Missouri’s prisons for the last dozen years. He’s been buying records at every stop along the way.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal