WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: On “Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter” and Loving the Bloat

by Baxter Smith

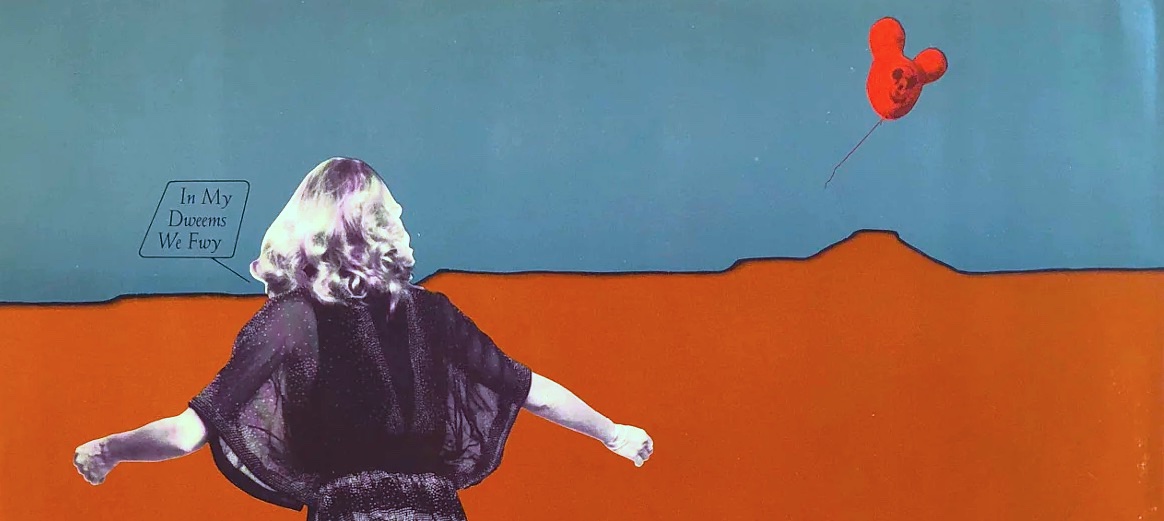

On “Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter” and Loving the Bloat

When I first heard Joni Mitchell’s polarizing and underdiscussed 1977 double LP, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, I didn’t much care for it. I appreciated its sprawling nature and orchestral flourishes, but the songs themselves felt distant and obscure. They were unlike anything I’d come to expect from the masterful author of “All I Want”, “Help Me” and “Amelia”. Since then, I’ve gained context for the album and my appreciation has grown significantly. I could never call it a favorite, particularly among a career that includes the vaunted peaks of Blue and Hejira, but I find myself drawn to its textures time and time again. I’ve purchased, sold, and traded several vinyl copies on the path to a “perfect” version, which wasn’t hard considering, if anecdotes are true, this is one of the most returned records in retail history. Reflecting on what changed after my initial dismissal, I’ve come to understand something about the relationship I have with indulgent or “difficult” albums.

Like Van Morrison’s A Period of Transition from the same year, DJRD succeeded a dense, personal, initially underappreciated LP that didn’t sell as well as its predecessors. For Joni, it didn’t seem to bother her that a portion of her faithful audience found 1976’s Hejira a confusing departure; her next outing proved even bolder. One has to admire the risks she took, utilizing numerous cutting-edge recording techniques and continuing her collaboration with notable jazz musicians Jaco Pastorius, John Guerin, and Larry Carlton, while also involving first-time collaborators Don Alias, Alex Acuña and Manolo Badrena, the latter three of whom contribute Latin percussion throughout the LP.

The album begins with “Overture / Cotton Avenue”, a suite that announces Joni’s intentions loud and clear. Fragmented guitar parts and disparate vocals arise timidly, swirling within the wide stereo spread. Such vocals are only possible through multitrack recording since Joni does every part herself. Though no stranger to such studio trickery (listen to the chorus in “Rainy Night House”), everything is pushed to the limit here. And regarding the discrete guitar tracks, a note from the official website indicates that “of the four guitars audible on the intro, three of them are normal 12-strings and the fourth sounds like it has only the upper octave strings for the third to sixth strings. In other words, it’s a six-string guitar (in CACFGC tuning) with the bottom four strings tuned an octave higher than usual.” That’s certainly a lot to throw at your audience within the first few seconds. After the initial parts coalesce into a robust harmonic spine, Jaco’s muscular bass asserts itself with a provocative solo. After, Joni launches into the song proper. That this and the rest of the tracks make heavy use of improvisation and studio manipulation show how particularly adventurous she was during this period.

Considering this album utilizes many musical styles and song structures, the manipulation can actually serve to unite incongruent ideas. Case in point, one of my favorite sounds on the LP is this bifurcated guitar effect that sounds like two instruments simultaneously playing the same part in either ear (headphones help). It appears first in “Cotton Avenue”, then again in “Talk to Me”. Similarly, Jaco’s bass technique, in conjunction with the way it’s mixed (read: hot), provides consistency from song to song.

A revealing example of Joni’s philosophy with this album arrives with the centerpiece, a 16- minute epic that monopolizes side two. “Paprika Plains” emerged from a series of extended piano improvisations that were later snipped and rearranged before orchestral parts were added, including an extended break in the middle where vocals drop out entirely. Way cool. The song itself offers many topics for a listener to plumb, including observations from a dingy dancehall bathroom, a detailed evocation of Joni’s childhood, observations on the hardships of Native Canadians, a picaresque travelogue through a post-apocalyptic wasteland, and a return to the dancehall for an arresting, head-bobbing finale. I’ve interpreted the song as the tipsy musings of a wandering mind during a bathroom break, but the possibilities are myriad.

Keeping with this song, the high note on the phrase “smashed on railway avenue” electrifies me, partly because Joni abjures her familiar falsetto for much of the rest of this album. By this point in her career, she’d reduced or abandoned many of the tropes with which she initially built her audience, deploying such elements restrictively to leave space for new ones. Indeed, “Paprika Plains” showcases a dizzying number of ideas, which, in my opinion, are additive rather than competing. By the time we reach the pumping jazz denouement, there is a palpable emotional release that speaks to the broader power of expansive, indulgent art. Sometimes it’s good to be overwhelmed, to feel surrounded, small, like one’s only choice is to give in and be carried away by the tide.

Favorite moments elsewhere in the LP include the icy, echoing bass notes on “Jericho” and “Off Night Backstreet”. I find that these anticipate the art rock sonics of Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, and John Martyn. I also dig the low tuned guitar on “Otis and Marlena”, whose texture resembles classical Spanish guitar and suits the international vacation motif. “The Tenth World” finds Joni at her most experimental, engaging in a churning, folksong-like interplay with several other musicians. Off-mic chatter and laughter add intimacy and looseness. The title track sees a return of the bifurcated acoustic guitar as well as a plunging bassline that required Jaco slide his fingers along his fretless bass until they bled. Worth it, in my opinion… The album concludes with the quiet “Silky Veils of Ardor,” a melancholy tune that harkens to Joni’s earlier acoustic style. It’s just voice and guitar. With all her ambitious excesses, Joni shows us in the final moments of DJRD that she can still nail a simple song.

The reactions then and now are polarizing, with one reviewer in 1977 finding the album “solitary and pessimistic”. I appreciate the smattering of recent reappraisals. One of my favorites appears in a ranking of Joni’s albums for Stereogum (DJRD comes in sixth), where the author posits its “lofty ambitions bear fruit […] Each piece is filigreed with a subtlety and nuance rarely found in rock music.” And the conclusion: “Like many sprawling double albums, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter revels in its untidiness. It’s the sound of Mitchell expressing herself with verve, poise, and, above all, joy.”

There’s so much I love about this album. I enjoy grappling with its obtuse lyrics, mixed messaging, and off-putting structures because it makes me a more active participant in the art. At her best, Joni’s songs seem to bloom from the initial idea into unexpected shapes and colors that feel effortlessly spontaneous. By virtue of its overreach, not in spite of it, this album allows a peek into the workshop of an artist already known for idiosyncratic songwriting. Here is someone at the height of her powers taking risks that extend beyond her capabilities and making full use of every available resource afforded by her industry stature. In that way, it is a doubly personal document. I, for one, am terribly grateful it exists.

Baxter Smith is a writer, filmmaker, and record collector based in Los Angeles. He began collecting in 7th grade despite protestations from loved ones and continues undaunted to this day. Follow him on Instagram: @thebaxtersmith and Letterboxd: fantasticmrbax.