WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: On Grief, Neil Young's Harvest, and Folk Music

by Roger Feeley-Lussier

Every year it hits me a little later it seems. This year, it was while I was walking the aisles of our local supermarket. It’s April 21st again. The anniversary of my mom’s death.

Frances Kulpa Lussier passed away on April 21st, 2004 due to complications from a routine gallbladder surgery. She left behind our dad, three twenty-something kids, and a lot of unanswered questions.

I’ve written about my mother’s death before in the context of social media, but in the eight years since writing that essay, a lot has happened. I’ve gotten married, bought a house, and had two daughters – one of whom bears a nearly alarming resemblance to my mom.

Grief can take many shapes. Thanks to therapy and pharmacological intervention, I’m finally figuring out the geometry of mine. I find myself wanting, more than anything, to discuss the things she left me – like her record collection, specifically her copy of Neil Young’s Harvest.

Growing up, my mother’s small-but-specific record collection was a source of constant joy for me. It was heavy on early Beatles and Elvis, with a few Columbia House 1¢ specials from the early 80s peppered in. I loved to unfold the massive booklets of albums like the Jesus Christ Superstar cast recording to memorize lyrics and credits.

My first exposure to Harvest came when Neil Young performed “Needle and the Damage Done” on the 1996 MTV VMAs in tribute to musicians lost to heroin. My mom came downstairs and exclaimed, “Oh! I have that record,” and she ran back upstairs to grab it. I’d seen it in her collection but never gave it a second thought.

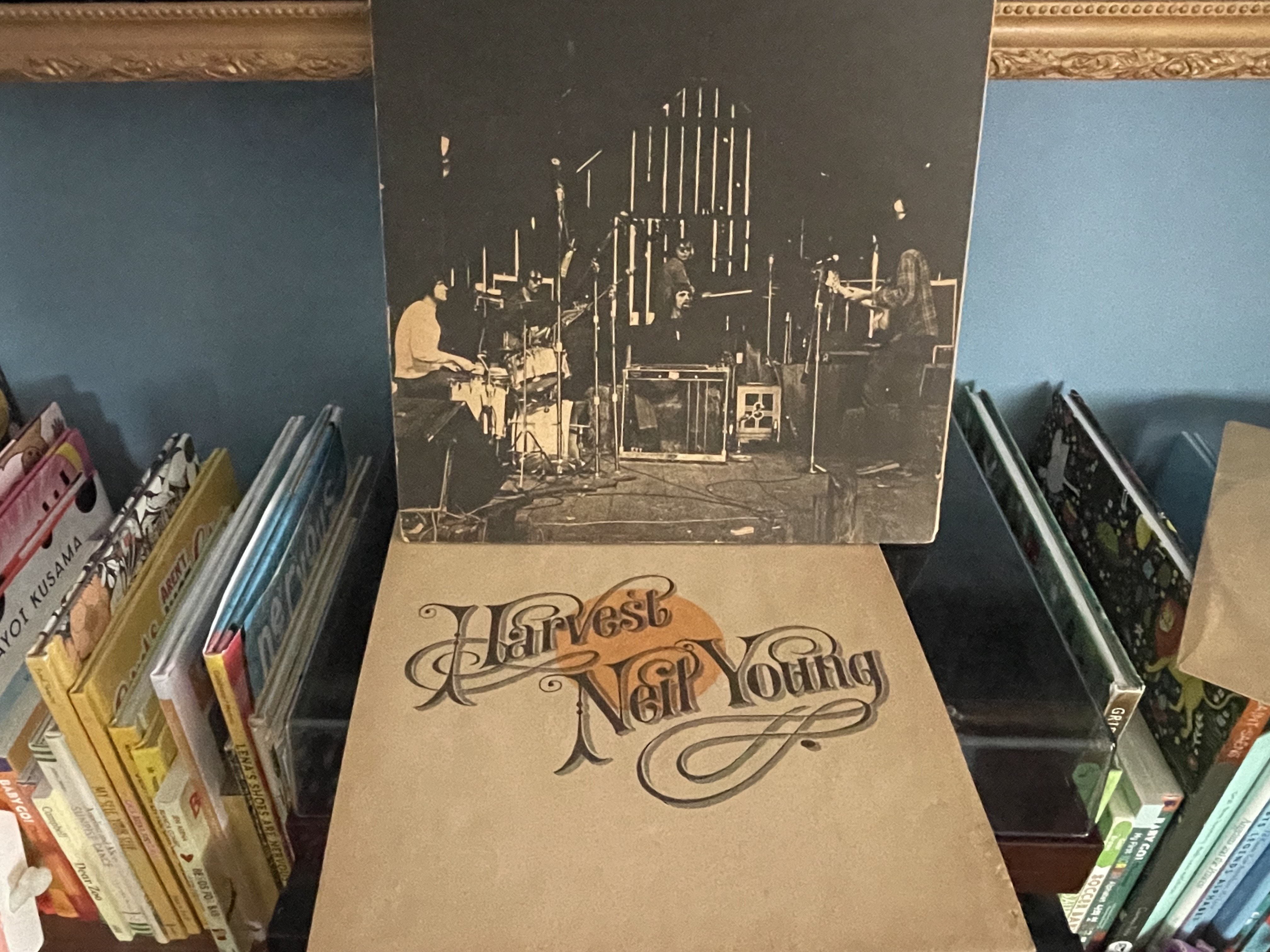

The back cover of Harvest, which I examined thoroughly that day in 1996, might be one of my all-time favorite pieces of rock and roll photography. It shows Neil and his band, set up in an old barn, light cracking through the seams between boards. This was a direct affront to the locked-down studio sounds favored by the 60s and 70s folk movement (Bob Dylan et. al).

That year, I bought her Harvest on CD for Christmas. She told me I could have her copy of the record – she wouldn’t need it anymore. We listened to her CD together, and I remember, for the first time, realizing how much it meant to her. How much music could mean to her. She told me it was one of her favorite albums. It became one of mine that day, too.

I didn’t realize it until recently, but this was something of a secret I carried. Last year, I texted my dad and sisters to see if they had any memories of mom and Neil Young. I was preparing for an episode of my friend’s podcast, This is the Greatest Song I’ve Ever Heard in My Entire Life, where I’d planned to talk about “Heart of Gold.” My dad said that he remembered her loving the album but not much more. My sisters both said they had no association at all with Harvest.

Legend has it, Graham Nash of CSNY got a preview of the unmixed album and watched as Young demanded “More Barn” (aka more chaos) in the final mix. Now, of course, we have no way of knowing if that really happened – it’s just mythology. Like I have no way of knowing how my mom felt about the individual songs on Harvest.

I’ll never get the chance to ask her how she felt about Neil Young’s harmonica playing. But what I will have are my memories of singing along to “Out on the Weekend” with my bandmates on our way to a basement show in Bloomington, Indiana.

I’ll never know how my mom felt about the way the London Symphony Orchestra breaks the silence following “Old Man.” But I’ll always remember the feeling of dancing around a diner patio with my eldest daughter as “Heart of Gold” plays. We get to assign our own mythology to the music we love.

Every night for the past three plus years, I’ve sung “Heart of Gold” to my girls as they went to bed. I’m so lucky that I get to introduce them to Harvest and teach them what I know about my mom, as well as my own personal experiences with the songs. There’s something potent about being able to create your own folk mythology in real time.

That’s what’s wonderful about folk music: it belongs to the folks (that’s us). Jack White says that when a song like “Seven Nation Army” becomes a sports chant, it no longer belongs to him. The meaning we put on top of music we love, that’s the modern version of folk music; storytelling and melodies passed from person to person.

And the best part? You can do it with any song. You have the power to put any meaning you want onto a melody and lyrics if you want. That’s your right as the listener. No one can take that away from you.

I’m so thankful that vinyl gives me this opportunity. It’s downright unbelievable that I can have a record from 50, 60, even 80 years ago and still play it in its original fidelity on modern gear. There aren’t many kinds of physical media like that.

Harvest came out in 1972, when my mother was 24 years old. I turned 42 this month, which means I’ve now lived half my life without my mom. The last she knew, I was still a film student getting ready to move out to LA. Everyone who knew her tells me how proud she would be of me. I hope that’s true. I’m trying to be the best version of myself.

There are a lot of things I’ll never get to know about my mom, but I know she loved Harvest, I know she loved music, and I know she loved my family.

All I can do is keep carrying her songs and the things she loved, to create positive mythologies using the artifacts she left behind. Folklore can be a powerful way to fill the space between unanswered questions.

For Frances Kulpa Lussier (2/28/1948-4/21/04)

Roger Feeley-Lussier is a writer and musician based in central Massachusetts. He has played in bands like The Appreciation Post and Pretty & Nice but mostly now just makes music with his solo project Perpetual Stu. He is addicted to the internet but trying really hard to kick the habit.