Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Scarred for Life

by Garth Jones

It’s, what, 1994? 1995?

You’re sixteen, anyway, on your regular post-school record store mission.

More accurately, it’s a RECORDS AND TAPES situation, though the CD is the ascendant form of recorded media. The shop’s owner, G.B., hasn’t had the coin to update the signage since he opened up in the mid ‘80s, though, and said records and tapes lurk, sullen and unloved, in the second hand racks and remainders bins.

You live in a tiny mining town in the surreally remote deserts of far western New South Wales, Australia. You haven’t seen it yet, but later in life you’ll refer to it as “you know, where Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 Australian New Wave classic Wake in Fright was shot” as shorthand when locating your point of origin in conversation.

Which is shorthand in itself for a place of tough blokes caked in lead and zinc, a pub for every hundred people, a place so perplexingly regional, outside of time, that it’s often referred to as The Walled City.

The youth radio of the east coast, an unfathomable third of a continent away, has failed to breach containment, and the Internet is something you read about in the American magazines that arrive in the newsagent a full six months after their cover date.

You, yourself, are anachronous to the prevailing vibe of the musical times.

Out here, that vibe means country and western, blokes called Kevin Bloody Wilson or Rodney Rude, and the incremental arrival of the Seattle sound and its impractical subcultural armor, flannel. (It’s regularly forty plus degrees plus out there, man. Celsius.)

Your vibe is more that of a hair metal connoisseur, a devotee of the Aquanet set, a genre that’s subject to even more ridicule than the Heavy Metal Parking Lot wannabes who smoke rollies and give out stick and poke tats at the fringe of the ragged school lawns.

You throw up a greeting to G.B. (or Gary, if you get to know him). Gary is very, very out, an incomprehensibly subversive act in that era, in those climes.

None of us kids register it, couldn’t care less. He’s G.B. He’ll order anything in for you, off of the computer.

You’re more of a compact disc kid these days, a tape graduate after your hazard-red boom box was retired for a multi-CD changer – a real cosmic array of LEDs and chunky subwoofers – at your last birthday.

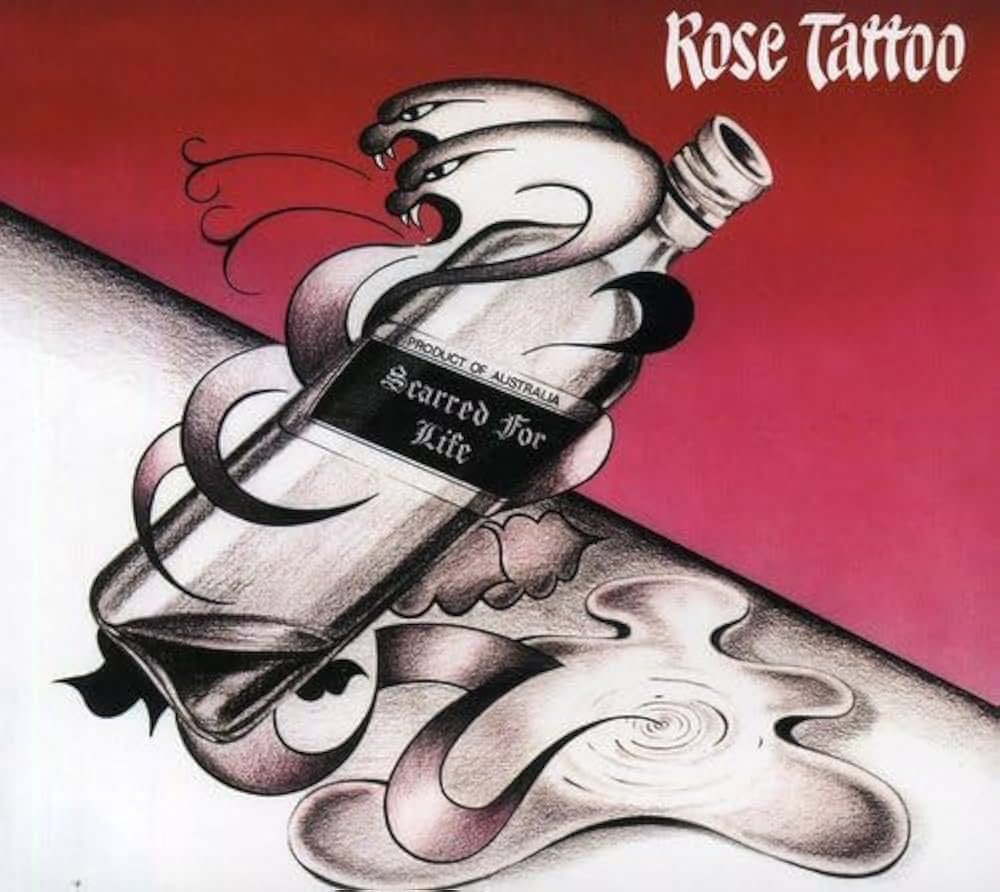

Even so, today it’s a twelve-by-twelve inch slab of gritty monochrome tattoo flash against a merlot sunset that arrests your eye – squatting at pole position on the five buck vinyl rack is Rose Tattoo’s Scarred for Life (1982), its cover a primitive beacon, defiantly declaring it’s a PRODUCT OF AUSTRALIA.

Reverently unseating the album, you take in the rough-hewn majesty of the sleeve.

You’re about eighteen months away from your first ink, but the primitive, shaded cover art – twin vipers insinuating themselves around an almost empty bottle of whiskey? – reeks of the blurred indigo artwork adorning the biceps and forearms of your old man’s workmates.

Top right, in an unfussy, vaguely oriental brush type, is the band’s name. It’s transgressive, almost savage, the antithesis of the chromed logos and airbrushed glamour shots of your usual go-to preening pop metal fare, imported from half a world away.

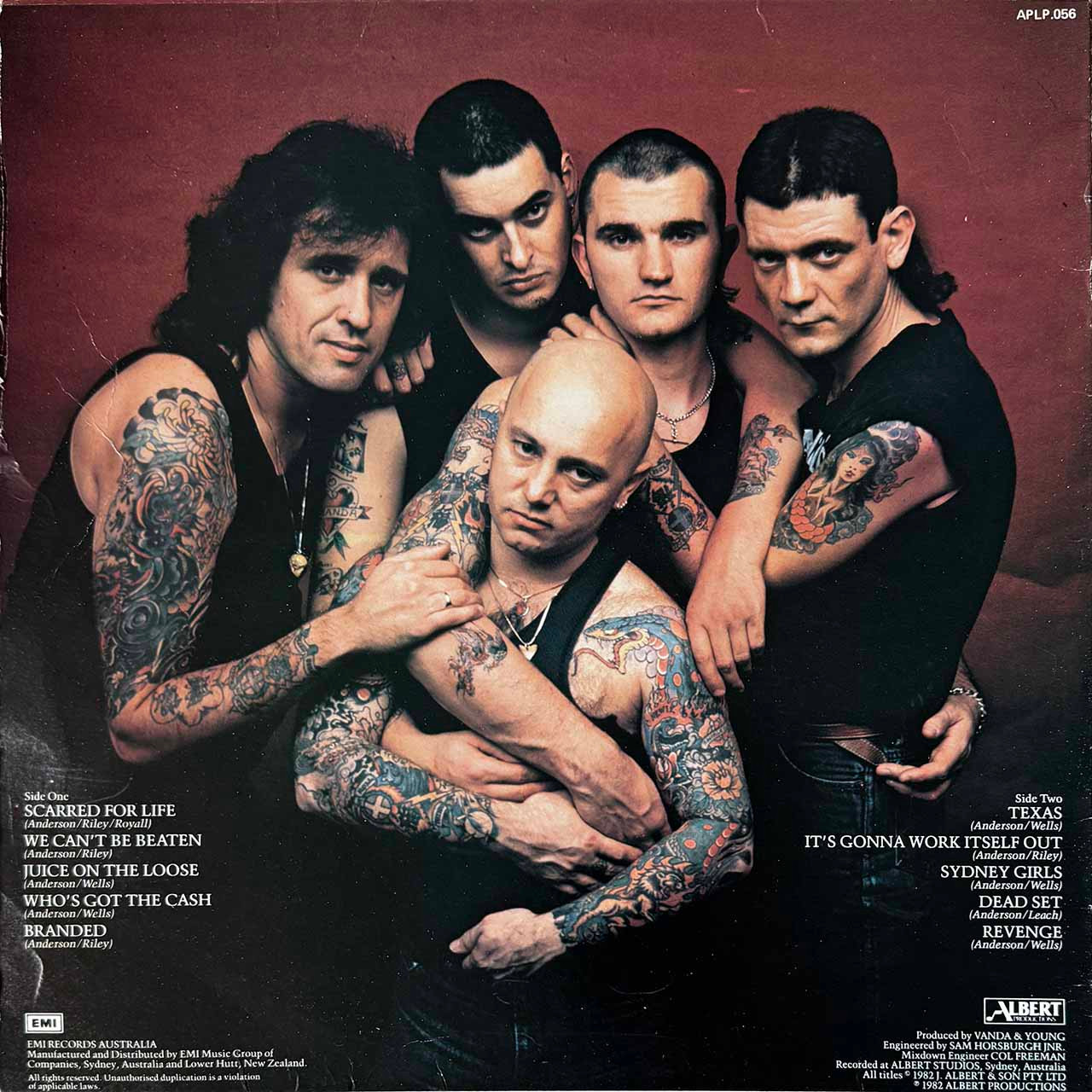

You flip the sleeve and are rocked by a tangible sense of physical danger. Five of the roughest blokes you’ve ever clocked, a seething huddle of prison tats, number one bladed mullets and vice-deadened eyes, leer up from a well of blackness, an aesthetic mugging in progress.

This is a contradictory masculinity, simultaneously magnetic and repellent.

This is no deviant pose, no gaggle of elegant wastoids, pale, razor sharp hip bones clad in calf-skin Varvatos and pre-ripped New York Dolls tees, designer sunglasses propped on expensively powdered septums, make up just-so, private jet fuelled and prepped for another prefab no-show.

This, this is Australian rock and roll authenticity, bloody knuckled, born and bred in the hard scrabble, working class suburbs of western Sydney, where brawls and booze and vice are the lingua franca of the post World War 2 melting pot. This is the music that the great-great-great grandsons of convicts, the scum of the British Empire, make.

Your ancestors.

Your story, imbued in PVC.

The brigands are bracketed by ten track names, five each per side, every one a hissed, veiled threat in roman serif: Scarred for Life / We Can’t Be Beaten / Juice on the Loose / Who’s Got The Cash / Branded and on and on, leaving zero doubt in your mind that these switchblade raps are bona fide.

Then, the decision’s made, like that.

This is your first vinyl purchase.

There’s no need to spin it, you just know. It’s primal.

The artifact has to be yours, never mind the fact you’re not really allowed to touch Dad’s record player. That’s for Gilbert and Sullivan and Rodgers and Hammerstein, really, an oasis of bourgeois taste out here in the feral wastes, a story for another time.

Maybe, just maybe he’ll make an exception for Rose Tattoo, you kid yourself, snatching up the contraband.

You deposit a handful of change – dollar coins, a jumble of fifty cent pieces, a few twenties, a lot of fives, definitely five bucks in total – onto Gary’s counter, offer up some perfunctory small talk and make a break for your BMX, loot stowed under your arm, those whorls etched in vinyl a cosmic gateway to transcending your present psychogeographic reality.

You are scarred for life.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal