WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Test the Meddle: a mother-daughter interview and short story

by Scarey Mulligan

During a visit home, my parents let me rummage through their crate of records. Since there were a great deal of duplicates, a side effect of moving in together and never taking inventory since, I was allowed to take whatever caught my eye. Among Janis Joplin, Black Sabbath, early Rod Stewart, and a surf album my uncle stole from a date and stashed with my mom, there was a smudge of blue: my mom’s copy of Pink Floyd’s Meddle. I held it aloft and she lit up: “I used to listen to that all the time in my first apartment!” For this piece, I called her up to talk about the album and about the time she stabbed a guy.

Scarey: Hi, Mom.

M: Hi, [redacted].

S: So I’ve got notes on Meddle, I know you have yours too, and I want to compare them. But first, tell me the tale of stabbing your pervert neighbor!

M: (laughs) Okay. My bedroom was really small, so consequently, there was a window, and my bed squeezed against a wall, just enough room to walk from the door into the room. The wall against my bed was shared (with the apartment) next door.

M. was in her final stretch of university, dividing her time between attending classes and teaching at the local high school. Her childhood dream was to be a teacher, and for the most part, it hadn’t yet tarnished, even when her supervisor would vanish into the teacher’s lounge as M. taught. The kids weren’t unruly, they were mostly receptive to M., but it was starting to feel like she’d been fed to the lions.

S: How’d you come across Meddle?

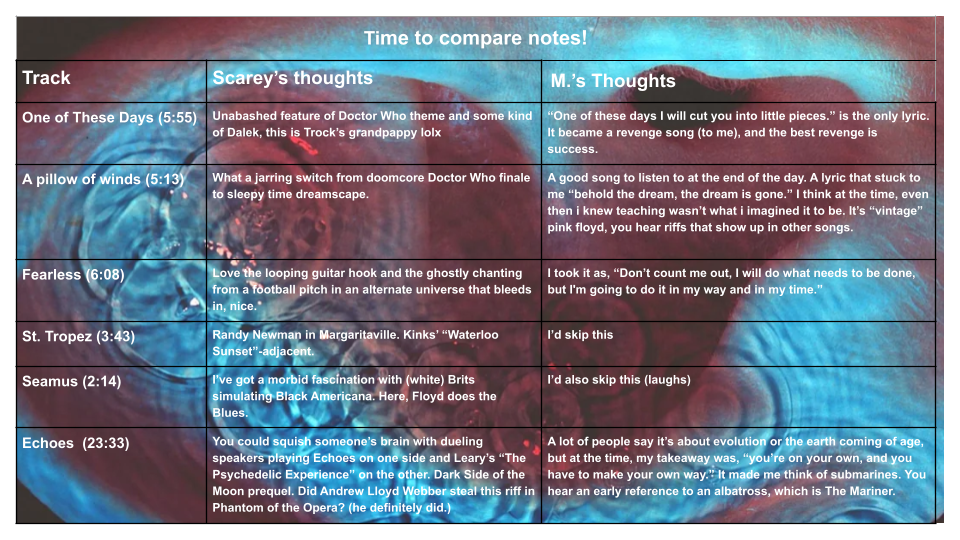

M: I probably just found it in a record store and went “oh i missed this” and just picked it up. Which is a risk (…) I don’t think they had totally figured out where they were going as Pink Floyd, so there’s a little bit of growing pains. Something like Echoes isn’t really going to get you in the top 40. But you can hear [Dark Side of the Moon] in that.

S: Tell me about using it to get ready.

M: I wouldn’t necessarily play it every day (…) but it was a mood thing, “What do I need to hear today?” Fearless got a lot of play, because I have to stand in front of these kids, act like I know what I’m doing, like I’m not afraid, and hope I’m doing good. I took it as, “Don’t count me out.” I will do what needs to be done, but I’m going to do it in my way and in my time. Listening to it in the morning as a psych up thing, I did that for years. I would do that in high school. When I was a teacher and studying Russian, I would study to music.

M. lived in a two bedroom apartment on the main street of S—. She worked in her room. It was cramped, her bed shoved against a wall and despite the desk crammed in the narrow space remaining, M. would opt for lounging on her bed as she put together lesson plans. Since childhood, M. would play records as she worked; the extra stimuli tripped a wire in her brain that triggered her tunnel vision. Thirty-ish years from this moment, she’ll explain to her elementary-aged daughter: “The ceiling could fall around me and I’d never know,”

S:I can’t really focus when I’ve got music playing.

M: Really?

S: Yeah, I just start listening to the song instead of whatever I’m doing.

M: It came and went as I entered adulthood, especially when I started driving myself to work and had complete control of tunes. Just songs that would put me in a focused, “I’m going to do it, I’m going to step up” frame of mind. I think this type of music, whether Pink Floyd or Moody Blues, it’s not about listening for every note or what the bass guitar was doing or even the lyrics necessarily, it was (…) just be with the music.

M. sat on her bed, annotating her work as she played her record. Faint scratching hid under the chords tumbling from the player. A lull between songs allowed the tiny krrtch… krrtch… krrtch… to breathe. One palm pressed to her notebook’s pages, M.’s free hand hovered mid-air, interrupted in its reach for a sharpened pencil. She watched the point of a hand-held drill burst through the plaster, a trickle of dust scattering on her bedspread. Perhaps M. ought to recoil, but panic mixed with a dreamlike sense of unreality kept her still. The drill withdrew from sight. On the other side of the wall, a man’s palm brushed away dust. Blank within and without, M. let her hand drop and take hold of the pencil. Moving like a creature that’s dodged so many fanged and famished beasts in its quivering life, she leaned toward the hole. She aimed the point of the pencil into the narrow opening and swung her free palm against the eraser, forcing it through to the other side. The motion was a blink, a violent stab then withdrawal.

M: We had a neighbor, his name was John. And I remember your father saying, like, “Oh yeah, John the Baptist!” Like, they all knew him as this bible thumper, but I knew him as a creep. He was an evangelist (…) he did not like me or my roommate. Never spoke to us, but had his eye on us. We were two women on our own, we had jobs, and we’d, you know, have our boyfriends overnight.

On the other side of the wall, a man grunted in pained alarm. M.’s hands were steady and her palms dry. The panic had evaporated. Her spine hardened. Her wide-eyed hare fear was now a blind rage flaring in thorny tendrils across her body. M. threw her things aside and stormed into the common area, startling her roommate.

M: So I slapped a band-aid over the hole and just ran right next door.

M. pounded on John’s door. Out of stupidity, arrogance, or a combination of both, he answered. To M.’s fury, he bore only the faintest mark on his face. His attempts to mollify her, to convince her he’d not done what she claimed only enraged her further.

M: The only other time I ever felt that initial deer in the headlights panic (…) was as a 12 year old, playing outside with one of my friends. (…) We saw this man and we just froze. “Why is this grown man out here, this is where kids play?” We were both frozen. Eventually something finally clicks and we both run, and afterwards we’re both saying “Why were we frozen? Why did we freeze like that?” and then “We’re never gonna freeze again.” It was just part of every day that somebody was going to say some smart ass thing. I had to explain to D. (your father), and it was really the first time he ever had it explained to him, how women have to be aware that they are prey and men are predators. It had always been part of the package. It still is.

M. shoved John aside and entered the apartment. Whether he protested at this, she couldn’t say, whatever noise he might produce at her was the worthless spittle of a coward. She sized up the space, imagining the layout of her own apartment, stepping along the walls until she reached the spot parallel to her bedroom. There, she found a hastily taped up poster. She lifted it, and there was the hole.

S: And then what?

M: He tried to say he didn’t do it, that it was always there, that’s why he covered it. He played dumb and tried to weasel out. I let him have it. I can’t remember what I said, but it wasn’t anything good. And I remember my roommate in the doorway like, “Yeah!” (laughs) He never bothered us again.

S: Do you recall what record you were playing during all this?

M: Oh, probably Crosby, Stills & Nash.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Scarey Mulligan is a performer, overthinker, and the Criterion Closet’s worst case scenario. Based in Los Angeles, they write about pop culture’s unbreakable bond with capitalist decay in a free newsletter, The Parasocial Hour. You can also find them on Bluesky.