How Doo Wop Saved Me

Published on Nov 2, 2025

The 45s of My Youth: You Don't Have to Say You Love Me

Published on Oct 21, 2025

When Bad Albums Happen to Good People

Published on Oct 11, 2025

Fall Into Winter: songs for seasonal transition

Published on Oct 5, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: The 45 That Survived the House Fire

by Maggie Peter

When I was eight years old, our house where we lived caught fire, leaving it as ashes. The fire started in the kitchen, and within a short time, it spread to the small rooms and destroyed curtains, furniture, and photographs. And before daylight, there was a black object, which was fattening where our house had been, and traced against the white sky. The smell I will never overcome is the smell of smoke and wet ash, the smell of the terminations.

During the days that followed we searched the ruins in search of items to salvage. It was a thoroughly hopeless state of affairs. There was no longer the old soul and the Motown singles that my father used to love as a child. They were crated into a box of wood beside the record player and vaporized into a piece of unknown metal.

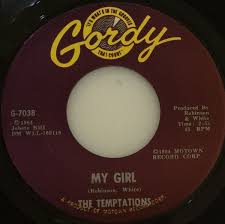

I was able to discover something substantial and round, despite the situation, when I was looking through the soot. It was a 45. The label was scalded on the edges, perverted, and even burned, yet I had the chance to read the dissolving print: The Temptations, My Girl.

However, that little record was the only thing that was left behind.

I remember that I gave it to my father, whose face was beetroot-red and whose eyes were shut with exhaustion and tears. He touched it like a holy thing the way he did with his fingers. “Would you see what this is?” he said to himself. “Still here.” He smiled, and he had not been smiling since the fire.

It happened to be bigger than a 45 vinyl record. It turned out to be the memory that all that is beautiful does not vanish once the world becomes mean. My father put it in a plastic bag and stored it in a drawer of his new apartment. He never tried to play it. The grooves had been deformed forever. However, there were times when he would remove it, place it against the light, and hum the melody to himself.

This record he left to me on his death. I have placed it in an equally miserable plastic envelope. Shelf against the later records, the fresh ones that sound good when I get them on my shelf, but none of them has the same meaning as that melted disc. I remember that occasion and what we lost and had when I view it.

It is peculiar that something so shredded is worth more than something so spotless. The 45 record did not play, and the music still lingers in my mind. I am able to hear the crackle, the sweet bass of the openings, and the emotional, out-of-tune singing of my dad. Not even the collectors in perfect condition, talking about the fire burning almost everything, could get rid of that sound. However, this record is not in line with any expectations. It burns, fuses, and ceases functioning. But in a sense it is the best thing that I possess. It has recorded our family history on it, both on memory and on vinyl. It reminds us of the fact that music does not only constitute a sound but also a warehouse of emotions. Songs that we are drunk on belong to us: our will and our joy, our sadness.

I am an adult collector of vinyl, and this has been one of the greatest aspects of my adult life, and I will never see myself as a serious collector. Rare items do not excite me. And when I steal a record off a market or a dingy store, I am seeking something living. There are others that are first pressings or even color versions; I am after echoes. I believe I can play it now because I was interested in the first Smick record I listened to, the one that did not wear out.

The waves are perversely made into lines, and the label is burned to the extent of abstract painting. I can also imagine the image of the leaping and skipping needle, the rotating and straining turntable, and the buzzing and static speakers. But maybe that’s the point. The song is sung; it has already gotten its job done. There is no longer any need to sound just right.

According to my father, the music is time. When any record was turned on, it was time to have a rest before they became extinct. I recall how my father had flinched his head on hearing the initial songs of My Girl and how his eyes would close as though this song was capable of taking him away. Or perhaps it was the record doing that; it brought us back to gloominess and told us that even ashes could sing.

A damaged 45 record would be incongruent in a world where DJs save their music on the cloud and the software is algorithmic. But somehow it is good to be holding onto that which is not dead. It is thick, it has a certain texture, and it bears scars. It doesn’t ask to be perfect. It is only purring with the thought of its immortality.

I put the record out of its sleeve and do it late at night in my palm. Big enough not to be forgotten, too big to lose. The outlines are jagged where they are needed, the lines are irregular, and it absorbs and reflects light to make it almost divine. It acts as a reminder that we are defined by what we possess and develop, although this may no longer be in use; documents that survived the house fire have shown their eternal worth. The cracks will not matter; the documents will be there. It is an act of retention, a rite of retention of something that has lost its fullness.

When they want to know my dearest record, I indicate something apart from the rarest issue or the most valuable discovery. I am referring to a small black disc that has a scorched label and an irregular edge; it never plays, yet it amplifies the music more than all the other discs in the house. Some of the songs never actually come to an end. They simply do not cease to discover new ways to be heard.

Maggie Peter is a Kenyan author who addresses the themes of remembrance, music, and self. Her works tend to be the results of her life experiences, as she tries to find out how sound and narration can make the memories that time has tried to forget come back to her. She reflects on the emotionalism of things, the strength of persistence in defeat, and the strength of nostalgia, which cannot be explained. She uses her time between the writing; she is rooting in crates, finding old vinyl that is still playing as it scratches between the recordings.