How Doo Wop Saved Me

Published on Nov 2, 2025

The 45s of My Youth: You Don't Have to Say You Love Me

Published on Oct 21, 2025

When Bad Albums Happen to Good People

Published on Oct 11, 2025

Fall Into Winter: songs for seasonal transition

Published on Oct 5, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: The Day My Record Player Picked the Wrong Speed

by Atieno Raphael

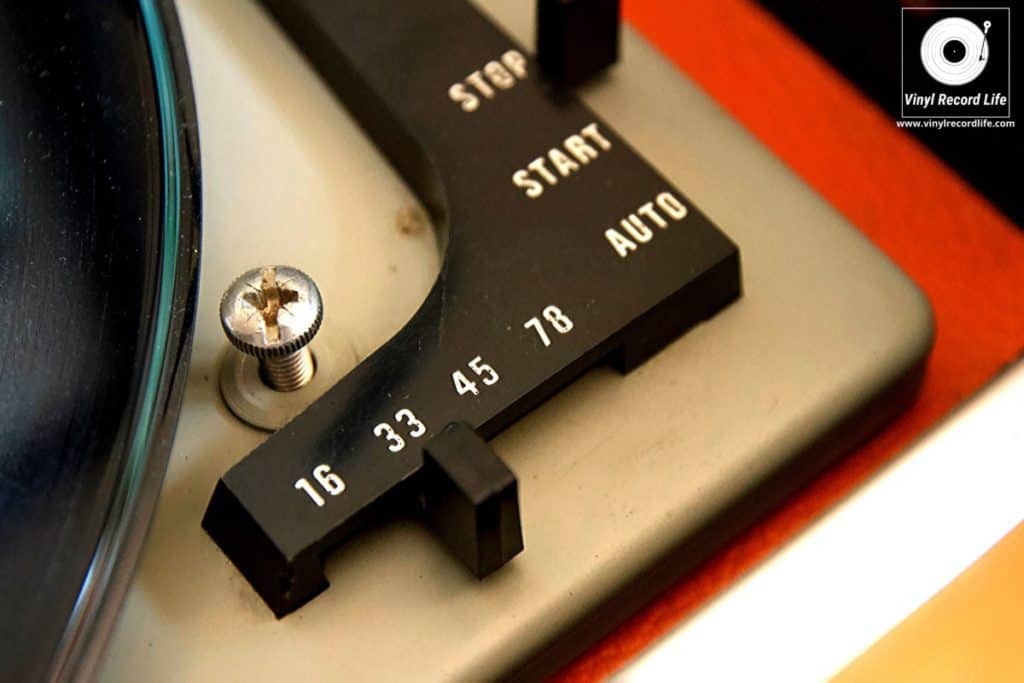

It was a mere, idiotic tragedy. One morning the turntable which I had bought in a second-hand shop that smelled of mothballs and regrets informed me that it could not continue playing 33 RPM. It would only play at 45. Nothing to compromise, nothing to change anything; it was pure defiance.

London Calling by The Clash was the first casualty of this problem, and it was my favorite punk record. As I inserted the record, I anticipated hearing the familiar, fast-paced track, “Clampdown”. Instead, the speakers had invented a dirge, slow, dense and mournful. The sneer of Joe Strummer was an apparition. The guitars, which were typically sharp and strained, now sounded like long sighs echoing.

This was my automatic reply because I flicked the switch, which now was not at the 33 setting. Snapped off, vanished. I sighed, and thought I would go digital; however, there was something there: curiosity, maybe, or that strange beauty of listening to an anthem slow down to slow motion. I no longer felt irritated at the conclusion of “Spanish Bombs”. I was mesmerized.

The next day I did the same with Ramones Mania. What appeared was comic and spooky: Joey Ramone talking like he had been sedated, as he tried to dance. This observation was not only incorrect, but it was also right. Songs that I would have seriously thought were hymns of insurrection when I was an adolescent sound so soft and wearisome. The cymbals were not crashed but moaned. “Blitzkrieg Bop” was made into a lullaby.

At this point, I realised that the revolving door in my life had become my accomplice.

The world of physical things is a world of analogue, with errors. You can touch them, hear them, and even love them. The pops and hisses are not the undesirable aspects of the vinyl; rather, it is the record being subjected to suction. And during the failure of my turntable, the music gave me the impression that music is a living being, that it is energetic, willful, and ecstatically unthankful.

I began experimenting intentionally. I dragged albums that had influenced my life: Bowie’s Low; Patti Smith’s Horses; and Miles, Kind of Blue. They were played at the wrong speed, and they transformed. Bowie was like a monk who has gone into meditation; the voice of Patti Smith was a wave that crashed in slow motion; Miles Davis became a movie, like a soundtrack in a dream.

Friends thought I’d lost it. ‘You hear swamp,’ another one replied. Maybe. I wasn’t seeking novelty; I was seeking something strange, the familiar becoming strange, an old sound revealing something new.

The lesson of listening at the wrong speed opened my eyes to the fact that we are in a world where people are so obsessed with being right. Digital perfection leaves no chance of errors, whereas vinyl does not demand accuracy. It buzzes, it jumps, and, as it happened to you, it shocked you.

All the scratches on a record are tales: the hole which plays a hi-hat in an endless loop and the slight crack which seems to be a breath between the notes. Those weaknesses are artistically accidental. That faded away when digital music replaced it. Everything became too clean.

When my turntable got out of order, it did not seem to me like a failure anymore; it seemed like an invitation.

I started to refer to it as the Wrong Speed Sundays. I would select a record each week, adjust its playback speed, either slowing it down or accelerating it, and compose a brief reflection on what I heard. Nina Simone at the slow pace may cause you tears in varied ways. Metallica’s “Master of Puppets” evoked a sense of a world that was ending slowly. The consequences were hideous sometimes, but occasionally something beautiful had happened by chance.

One afternoon, my daughter entered the house while I was listening to Abbey Road at 45 RPM. She frowned, then smiled.

What is it with them? They sound like ghosts. she questioned.

I explained that they are playing through time.

And she reflected upon it and began humming along; though slightly off-pitch and nearly out of sync, it was nonetheless perfectly suited.

And that’s when I realised it was no longer about music. It was about giving up control and acknowledging the unexpected. Vinyl hints at the fact that beauty is outside of perfection and concealed in gaps, cracks, and unreasonable paces.

Since then, I have caused the turntable to go round, but I miss the insurrection. After all, when I flip the switch on, I am transported back to that slow, dreamy world. It reminds me of the day when a technical malfunction had been transformed into an invention, the day when a punk track was made into a prayer.

There has been a digital era that is obsessed with perfection, and my peace has been in my inability to accomplish it. My books don’t rotate; instead, they fall, speak, and breathe. I sometimes assume that the light cast over the vinyl is positioned perfectly so I can hear Joe Strummer’s voice stretching through the grooves, and I realize I never intended for the music to sound at one speed or any speed at all.

I’m Atieno Raphael. I grew up surrounded by music, with my father playing jazz tape records to me and my mother playing gospel 45 records, and I have been captivated by the analogue cosines ever since. Between Nairobi and London, I learnt to appreciate the unique scratches, skips, and warps that made each record unique. I also use my time to write about vinyl, go digging in crates sold outside markets, refurbish turntables, or tell my children about the value of side B. I think the flaws of music are similar to the flaws that make us feel like humans, and that is the reason why I will continue to play records.