Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: The Loneliness of the Night Drive: How 90s Trip-Hop Soundtracked Emotional Escape

by Israel Kolawole

The Loneliness of the Night Drive: How 90s Trip-Hop Soundtracked Emotional Escape

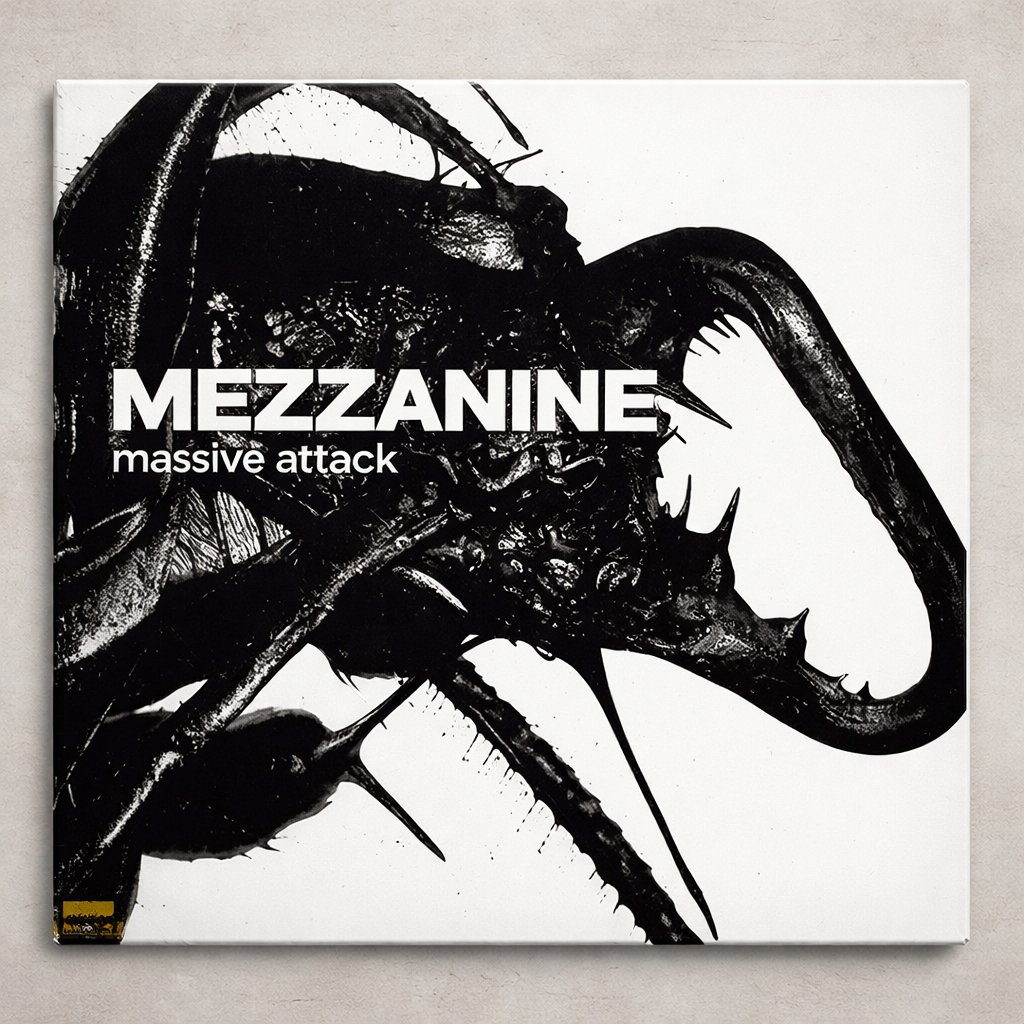

There’s a peculiar intimacy to driving alone at night. The streets are empty, the city lights blur into streaks against the windshield, and the hum of the engine becomes a private rhythm. For many of us growing up in the 1990s, that solitude was soundtracked by trip-hop: the shadowy beats, languid basslines, and ethereal voices of artists like Massive Attack, Portishead, and Tricky. These songs were not merely background; they transformed the act of being alone into a cinematic experience, rendering isolation as both comfort and introspection.

Trip-hop’s genius lay in its ability to make quiet moments feel loaded with emotional weight. Take Massive Attack’s Teardrop, whose syncopated percussion and Elizabeth Fraser’s haunting vocals create a suspended, almost otherworldly space. Listening to it on a night drive, the mundane becomes charged, streetlights take on a melancholy glow, and even the hum of tires on asphalt seems laden with narrative. The music’s slow, deliberate pacing mirrors the patience of being alone, turning a simple journey into a meditation on self and memory.

Portishead, in turn, leaned into cinematic melancholy. Songs like Roads and Sour Times inhabit that liminal space between comfort and unease, their textures evoking rain-slick streets and fogged-up windows. Beth Gibbons’ voice, fragile yet commanding, invites the listener into a space of vulnerability. The solo night drive, or the quiet room late at night, becomes a canvas onto which emotions are projected and explored. In these tracks, isolation is not emptiness but a palette of nuanced feeling.

Tricky’s work, meanwhile, introduced a darker, more anxious edge. On tracks like Hell Is Round the Corner, the dense, sample-heavy soundscapes suggest danger lurking just beyond the headlights’ reach. The music does not merely accompany solitude; it complicates it, layering in tension and unease. The act of moving through empty streets while this music plays is simultaneously soothing and alerting: a sonic reminder that the night holds both possibilities and shadows.

What makes trip-hop so enduring is its paradoxical approach to intimacy. The music is both protective and exposing. It creates a private bubble, headphones isolating the listener, while inviting confrontation with inner thoughts and feelings that are usually left unexamined. In a pre-digital era where being alone with one’s thoughts was more common, these tracks offered a mirror to private emotional landscapes. Today, in an era of constant notifications and digital noise, the reflective solitude they evoke feels even more potent.

The aesthetic of the night drive, the dim dashboard lights, the slow hum of tires, the occasional distant streetlamp, aligns perfectly with trip-hop’s sensibilities. The music transforms the ordinary act of commuting or wandering into something cinematic, where every turn, every pause at a stoplight, becomes a moment of introspection. This is a music that understands the poetry of ordinary movement, the emotional textures of time spent alone.

Trip-hop also revolutionized how emotional narratives could exist in popular music. There are no grand gestures or overt declarations; feelings are implied through tone, atmosphere, and subtle sonic shifts. This understated approach reflects the rhythms of nocturnal solitude itself: private, fragmented, and deeply felt. To listen to Maxinquaye or Blue Lines is to inhabit a state where external movement and internal reflection converge.

Ultimately, 90s trip-hop captured something universal yet intensely personal: the need to navigate isolation while retaining a sense of narrative and emotional depth. It made ordinary nights feel cinematic, turns down empty streets suspenseful yet comforting. And it continues to resonate today because, despite the evolution of music and urban life, those private night drives, moments of reflection, introspection, and quiet solitude, remain essential to understanding ourselves.

Trip-hop reminds us that being alone need not be lonely. It offers both a soundtrack and a framework for encountering ourselves in motion, in shadow, and in quiet contemplation. In the language of beats, samples, and whispering vocals, the night is never truly empty; it is full of possibility, memory, and the unspoken stories we carry with us on every drive.

Israel Temmie Kolawole is a culture and music writer whose work explores nostalgia, sound, and the emotional lives of listeners.

Previously by Israel: 80s Synth Pop