How Doo Wop Saved Me

Published on Nov 2, 2025

The 45s of My Youth: You Don't Have to Say You Love Me

Published on Oct 21, 2025

When Bad Albums Happen to Good People

Published on Oct 11, 2025

Fall Into Winter: songs for seasonal transition

Published on Oct 5, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: The Record I Bought for a Ghost

by Bright Douglas

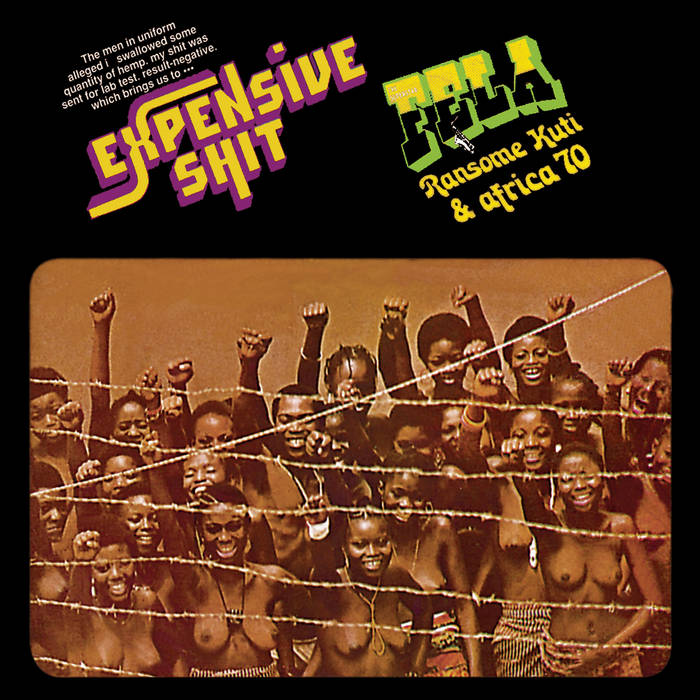

When my uncle passed away, his last hiss was heard on his turntable, and the dry rattle of the night in Nairobi left no memories behind him. The battered box under his floorboards contained his vinyl records, which he played at parties in the 70s, where it was like communion with the sweating palms and rotating plates of vinyl. One of them was a sleeve: bare and empty. The name was embossed in the dwindling gold typing, which read, ‘Expensive One by Fela Kuti’. No record. The very suggestion of the lines, which they lacked.

The picture of that bare arm had been tormenting me for many years. I would sometimes take my fingers and stroke the coarse paper and then turn it inside out, trying to find some trace, a creased angle or a slight smell of dusty paper. I had fancied enquiring what record there had been in the past, there was someone close to him; I felt connected to unspoken words and unsung songs.

Years later, on a golden Sunday morning, I walked through the busy flea market in Nairobi, where the sun poured over dusty record stalls as I sought memories that I did not yet realize I possessed. My shoes were naughty; my head was up in the clouds. On the heaps of books, broken radios, smart radios, shed radios, and teacups, I discovered a book the cover of which I did not recognize. teacups, recognize. recognize. The artist had color, recognizable color, ugly color, and free-flowing ugly lines. I flipped it, following it, and I had pictures of horns, sweaty musicians, and dancers dressed in striped tops. This was AfricaDelic, the sounds of Lagos. Something in me stirred. I purchased it without even giving it a second thought, intending to sell it as if compelled by superstition. The takeover would finally resolve the sense of incompleteness.

When I reached home, I laid the new record next to the blank sleeve of Expensive One. One of the registered homes was lost, and the other was available. Then I dropped the needle. The crackle was first heard, followed by the music, the horns, and the deep, rich rhythm. I listened to it, and I was mounted with feeling. Felt sad, but deep down I was relieved. Continuation. I strongly felt that music can communicate across time and convey messages even without words.

Then I learnt that deafness could be a form of heredity. It will earn the hereditaries. I’ll be able to cross the generations and retrace it to its birth. This strange group of Lagos and the music of Fela were somehow bound together on the same thread, as in the case of my uncle. Records do not truly outlast us; they carry our legacies. They carry the imprint of our legacy. They put our stories away and get them out after we are dead. I have absolutely no idea as to why I purchased that record. I must have felt the need to accept that what was unresolved could be resolved eventually and that the missing aspects could have a tone, must have wished to keep the man who taught me my earliest lesson in rhythm without changing a single word he said. Or perhaps I just had to be reminded about the usefulness of analogue items, such as the hiss, crackle, and touch of a record. They are a reminder that memories are also physical and that unhappiness is literally something that we can feel.

At the time of listening, I was thinking of what we inherit. We receive not only tangible things that we inherit, like a house, a ring, and a name, but we also inherit sound. It is the beat of our homes, the music that sleeps under our tails, which appeals to me. What I inherited that Sunday includes my hand, the impression of my uncle’s hands, the sleeve he had washed off, and the sleeves that may have been there before.

I can take out the Expensive One sleeve at an hour in the night and press the flea-market record on it. I presume my uncle was retrieving a needle while people moved about, and the air was stuffy and filled with laughter. The lost returns in one case. The silence between us is a sound-filled silence.

The sadness in music exists, but it represents a continuation. The gap can be bridged even decades later with the help of records. My uncle had started something, which I did not finish. I was going into a new thing, a new beginning, something delicate, something divine. I bought a record for a ghost. By so doing, I got to know that love does not fade when music is played. The needle always slides down into the groove.

Bright Douglas is an author living in Nairobi, and attempts to comprehend the emotions of memory, loss, and the ever-present sound of being. Her music shows how music may be used to reach across generations, turning grief into a beat. As a young girl, raised on the spindles of her uncle, she learnt in early adolescence that a record was not a sound but a heartbeat and molded it into a piece of vinyl. Bright collects African jazz and funk records and finds some ancient players just to recover the hidden stories in every groove. She praises the warmth of the analogue life and how music, like memory, never disappears; it just needs a human to take the needle back.