Garfield, Odie, and the Dead Vinyl Years

Published on Nov 4, 2025

How Doo Wop Saved Me

Published on Nov 2, 2025

The 45s of My Youth: You Don't Have to Say You Love Me

Published on Oct 21, 2025

When Bad Albums Happen to Good People

Published on Oct 11, 2025

More Liner Notes…

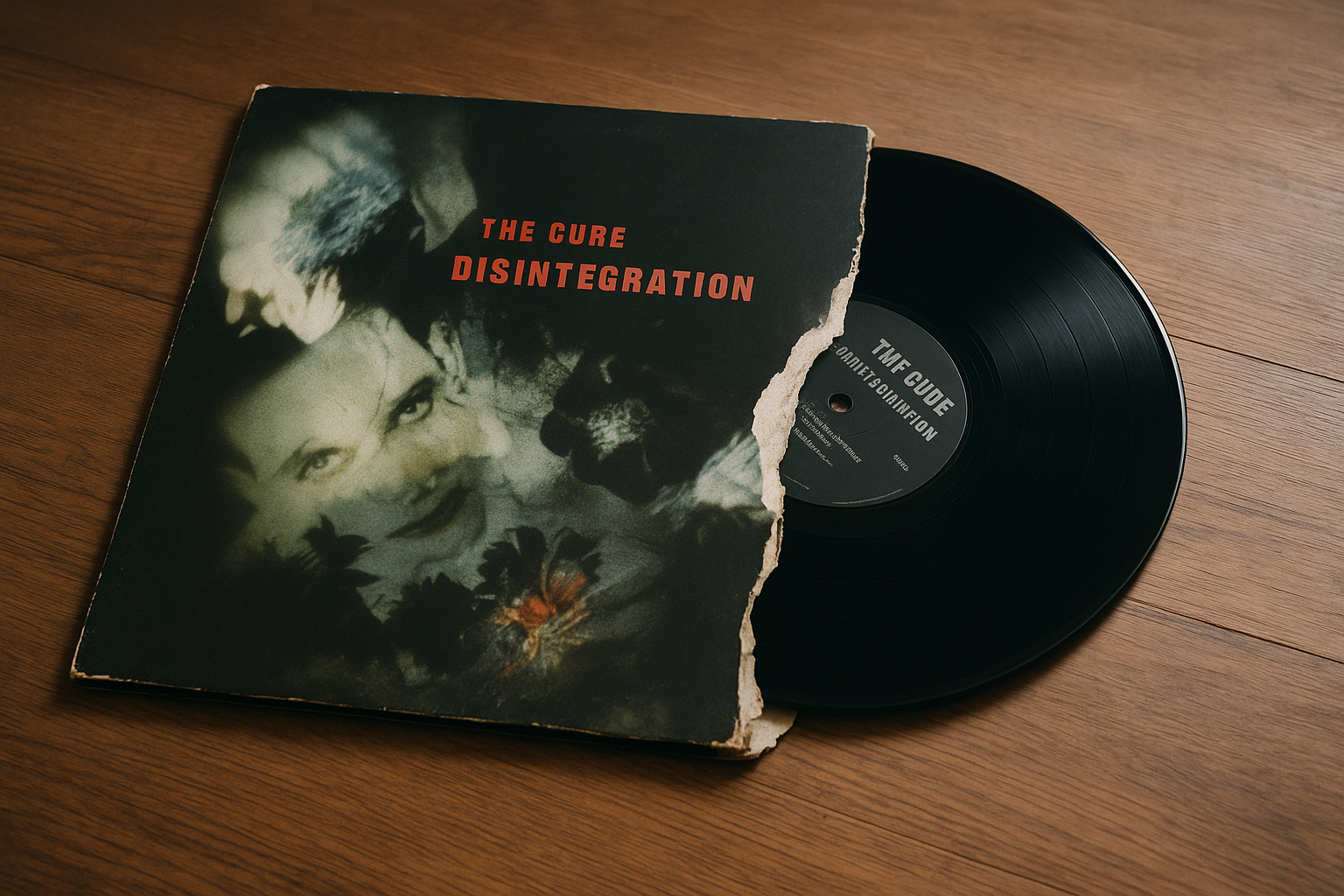

Featured Essay: The Record That Survived Three Breakups

by Mary Francies

The matte-black sleeve of Disintegration by The Cure shows signs of wear, like a scar I openly displayed, and I have carried it throughout my twenties. It initially came out when I left my first apartment: I put the record in a battered tote bag, and the edge got stuck on the metal lock of the strap, creating a tatty hole. Since then, the casualties have been adding up: cracks, holes, frayed edges, a footnote, a place I left, a version of myself I outgrew.

I can still recall the first time I turned the record in a new apartment. The needle fell down the groove, and that initial glorious rush of sound appeared to fill the room. There was nothing then; there were no heartaches, no indecisiveness; there was the voice of Robert Smith in the walls like a curse, later learnt that this album would be more than just another release; it would always be at the center of the changes around me.

I started to pack up my belongings again when the second affair ended in one of those silent break-ups that you experience, where both partners know it is inevitable but never fully accept it. I owned the record, but its cover had vanished, seemingly replaced by something else. I played it immediately when I removed it from the new flat, as a survival ritual. The Cure were singing of loss and of longing, and to some degree I imagined that they were singing to me.

The third separation was when I was more mature. I would put the record on the dark nights when I could not sleep, and I could feel the loneliness in my chest and the city seen outside through my window looked very far away. The apartment felt smaller because it had less furniture, although it still contained the vinyl record. I rubbed my fingers over the tearing cover, the scratched spine, the torn corner, and the plump edges that had been smoothed from being frequently touched when I found it behind the other records. The record was in excellent condition, although delicate. And somehow that was all.

Each time I was going to drop the needle, I heard not only songs. I heard radio hums in the middle of the night, quarrels over the nothingness, laughter from someone who had been in a kitchen, and the leaving echo. The torn garment was a testament to the fact that something survived all the endings.

I’ve realised that the recording is not exclusively musical. It is a form of remembrance and embodies all I have taken in through heartbreak and reinvention. Its flaws are my own, as they are the power, not the devastation. I never substituted it, and I could have easily bought another copy. Doing so would have erased its history, as well as my own.

It was a simple act of trust. Every time I listened to the same needle, record, and songs, they changed, as the music grew with me. That rhythmic groove serves as a place to revisit and discover beauty amidst the chaos.

Occasionally when I look at the sleeve now, I can no longer see it as broken but as an old journal or an overfolded photograph. It bears the responsibility of everything that happened and everything that never happened.

I am in another apartment. I have a window, which faces the street, and I can hear the rain falling on Sunday mornings. I listen to Disintegration and leave the sound to play in the rooms during such mornings. It doesn’t feel sad anymore. It is a homecoming song, as though you are listening to a close friend play a song that you have heard many times, but you like it anyway.

I have set the record as my silent friend. It has suffered and repented, it has been lonely, and it has been revived. I can no longer be proud of its torn sleeve: it serves me well. Objects have been used over time, yet they still serve their purpose remarkably well.

I would refer to it as a mirror of some sort. All the gouges, all the scratches, all the jump cuts I have heard about. It is not a very excellent sound, but that is mine. It is the sound of imperfection that makes me go there again and tells me that I do not need perfection to have a significant life.

It is something that you have to hold on to serve as a reminder of who you were and what you are becoming.

Ripping the jacket, the music is not leaving. Maybe, it has been attempting to remind me that love does not last long, cities change, and people die; but a song can live much longer than all these.

Mary Francies’ work explores the boundaries between music, memory and emotion and discovers poetry in the commonplace and meaning in music. She views all vinyl as two narratives, the narrative of the artist and the narrative of the listener, and her essays usually exist somewhere in the middle between the two. In her spare time when she is not writing, she is employed in a small independent bookshop, and on weekends she digs in crates of lost albums. Mary takes solace in the flaws of music and the manner in which a battered record can play.