Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: The Rise and Fall of the Triple Album

by Tim Foley (aka T.J. Wolfsbane)

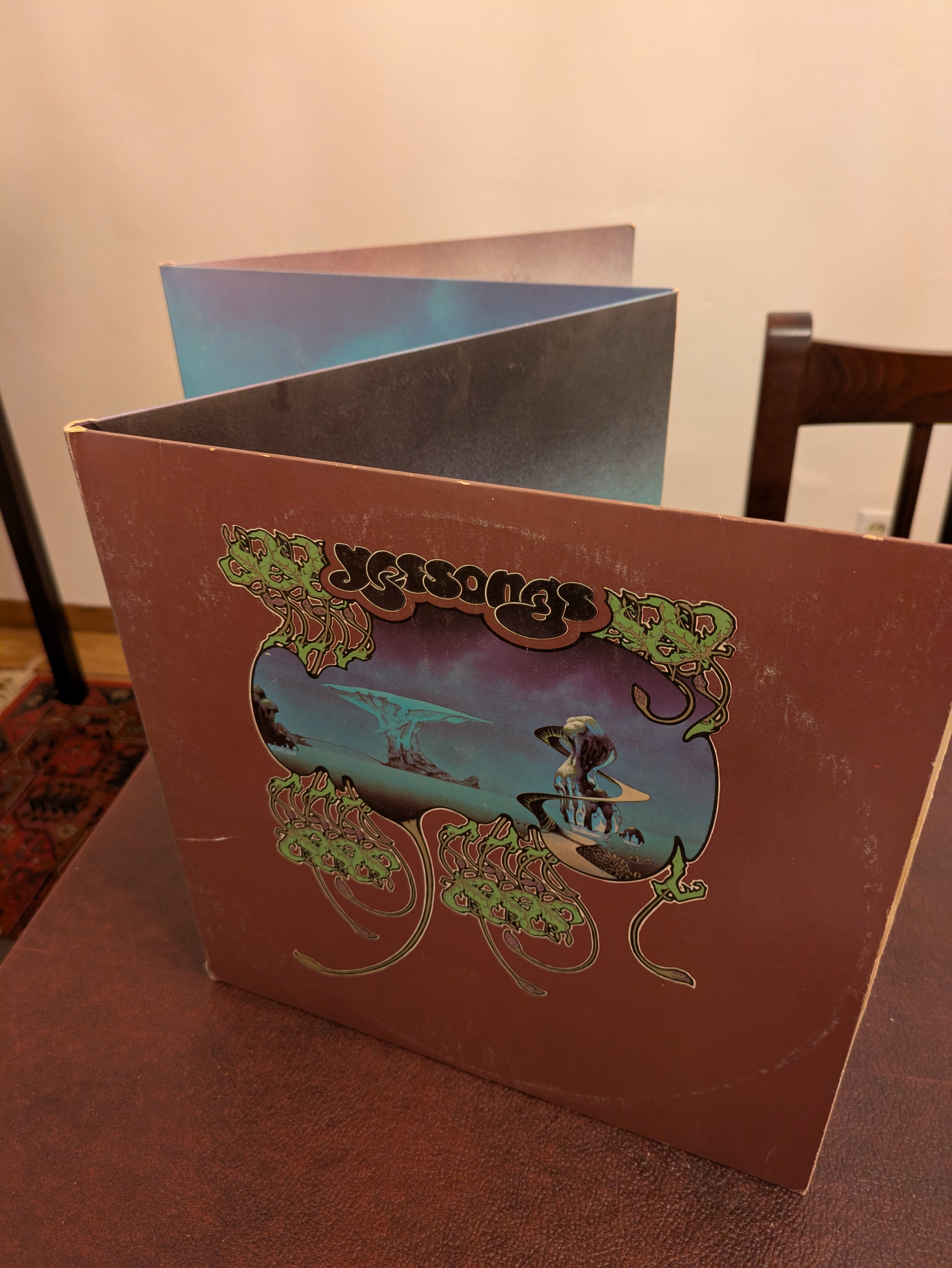

Recently, Jeff Tweedy released a triple album*, Twilight Override,* 30 tracks gathered in one place. The announcement made me think back to when I was a kid, in the record store, caressing the hefty Yessongs album with the legendary Roger Dean cover, lamenting the price, wondering if I would ever have the courage to spend that much money – it seemed a fortune – on a record. Ah, the triple album, vinyl’s indulgent dinosaur, two hours of either well-earned bliss or buyer’s remorse.

The development of microgrooves and slower turntable speeds in the late 1940s gave us the standard 12 inch vinyl disc maximum running time: roughly 20 minutes a side. In addition to the creation of a new art form (the album cover), the thin profile granted consumers easy storage. Album shelves and cabinets could hold a record collection with quick access and, the artist and title identified on the spine, easy selection.

Unsurprisingly, a need for capacity longer than 40 minutes, especially in the classical and jazz genres, quickly led to double albums. The design for packaging the double album was easy: simply create a fold along the spine and two sleeves. The basic shape and aesthetic remained the same, and the interior spread allowed for more images and information. In addition, the record companies soon learned that the increased cost of the double album could easily be recouped with an increased price. By the late sixties, double albums were reasonably common in popular music and took their place among the biggest sellers of the era: the Beatles’ White Album, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, Cream’s Wheels of Fire, The Who’s Tommy, Chicago’s first. The original Broadway two-disc cast album for Hair was a massive seller in the summer of 1969.

Inevitably, the roughly 70-80 minute timespan of the commercial vinyl double album became itself a bit restrictive, and maybe even a challenge. The first major release in the popular music context to go triple was the Woodstock soundtrack, issued in May of 1970, nine months after the festival, simultaneous with the release of the concert film. The need to capture a true sampling of that epic event necessitated the amount of music, and Atlantic/Cotillion Records’ faith in the project was rewarded. The packaging was a bit awkward, with an almost origami-like structure, but neither the oddity nor the higher cost deterred success. The album went to number one on the Billboard albums chart in July and stayed there for four weeks.

Leave it to George Harrison and the breakup of the Beatles, though, to push things into another realm. A triple live album is one thing, the foundational music all there, fed into the board. A triple studio album is a whole other creature. The compilation of dozens of tracks, properly produced, with multiple takes stretched over days, weeks, maybe months, would be an exhausting and expensive task. Harrison was, however, a Beatle, with his own (albeit badly mismanaged) record label and limitless studio time. And he was a Beatle with a grudge, correctly believing that his own musical compositions had been pushed aside by Paul McCartney and John Lennon during the last years of a musical juggernaut.

In 1970, Harrison had a bunch of great songs ready to go, and pulled together some killer players, including Eric Clapton, Bobby Whitlock, Jim Gordon, Carl Radle, Bobby Keys and Dave Mason. Phil Specter produced, and the collection was one of his triumphs. The sound was lush but not overbearing, and many tracks featured some superb slide guitar work from Mr. Harrison. The album served as a bold declaration of artistic independence by the underestimated, underappreciated Beatle.

All Things Must Pass was released in November of 1970. The three albums came in a cardboard box, with a rather uninspired poster and a hefty price. Buoyed by a number one single (“My Sweet Lord”) and the effusive praise of the surprised critics (many thought Harrison would simply fade away into irrelevance when separated from the other Beatles), the album was a smash hit. The industry was shocked when it outsold the solo albums of McCartney and Lennon, and topped the Billboard album chart for seven straight weeks at the beginning of 1971.

Yet, in retrospect, as great as it is, All Things Must Pass was, for those who purchased the original release, a bit of a rip-off. Bluntly: it should have been a double album. There are only, in truth, 17 songs (“Isn’t it a Pity” is presented in two different versions). The third, bonus “Apple Jam” album is an indulgent mediocrity, issued only because Harrison had the hutzpah to do so. I don’t know anyone who played that disc more than once. And the box was a pain: it was a problem to store with other albums and, inevitably, the corners would be crushed and split. When the CD format came along, sensibly, All Things Must Pass was issued as a double.

Still, by selling millions, All Things Must Pass proved that a triple vinyl album was commercially viable. The long grind of compiling a studio triple, however, remained a problem and a limitation. Rather, in light of the success of the Woodstock soundtrack, the seventies became the era of the triple live album. Such mega-albums were essentially greatest hits collections performed live and thus a format limited to bands that already possessed a large following. And, because the studio time was limited to overdubs, they were relatively inexpensive to produce despite the increased cost of packaging. Harrison himself issued The Concert For Bangladesh in late 1971, and then came live triple albums from Yes (Yessongs, 1973), Emerson Lake and Palmer (Welcome Back My Friends, 1974), Wings (Wings Over America, 1976) and The Band’s The Last Waltz (1978), all of them quite successful. The artwork and booklets contained in these releases added to their desirability and prestige.

Yet, the lure of the triple would quickly fade. The record companies noticed that the commercial appeal of a live double album was far more reliable. Frampton’s double, Frampton Comes Alive!, sold eight million copies in the USA alone in 1976. Kiss Alive!, also a double, sold nearly as well. The sweet spot for the live album thus appeared to be the double, not the triple. The triple seemed to require a huge, preexisting fan base, while a double had a higher upside and could launch a band into super-stardom, a la the Allman Brothers Band’s Fillmore album.

What ended the lure of the triple for good, perhaps, was the ambitious, pretentious, and politically provocative studio monster, Sandinista!, released by the Clash, the so-called Only Band That Matters, in 1980. The thirty-six tracks overwhelmed, and the sales (after their breakthrough London Calling) underwhelmed. While there was definitely a diversity of song styles, the English boys simply were not up to the task of creating a reason to listen to six sides and two hours of their music. Indeed, the band began to splinter during the effort. The critics were not impressed and only hard-core fans were happy. The next Clash album, Combat Rock, a single disc, succeeded where Sandinista! had failed both artistically and commercially. The labels learned the lesson.

For me, Yessongs remains a favorite album, packed as it is with songs that the group developed for years before incorporating into the live performances captured on the record. I prefer those versions to the more restrained, sterile studio tracks, and the length of the album is earned. But the indulgence of a two hour collection of songs, recorded in one long go, is something only granted to particular bands by certain devoted fans. As the Clash learned, the triple serves as a test that most bands would fail, and most bands, wisely, never take. All the best to Jeff Tweedy.

Tim Foley is a writer and playwright, living in Sacramento. His collection of ghost stories, Tales Nocturnal, was issued by PS Publishing in 2025. Long ago, he played guitar for a few Bay Area bands and, even longer ago, he was the music director of an FM radio station. His website: www.TimothyJFoley.com