Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

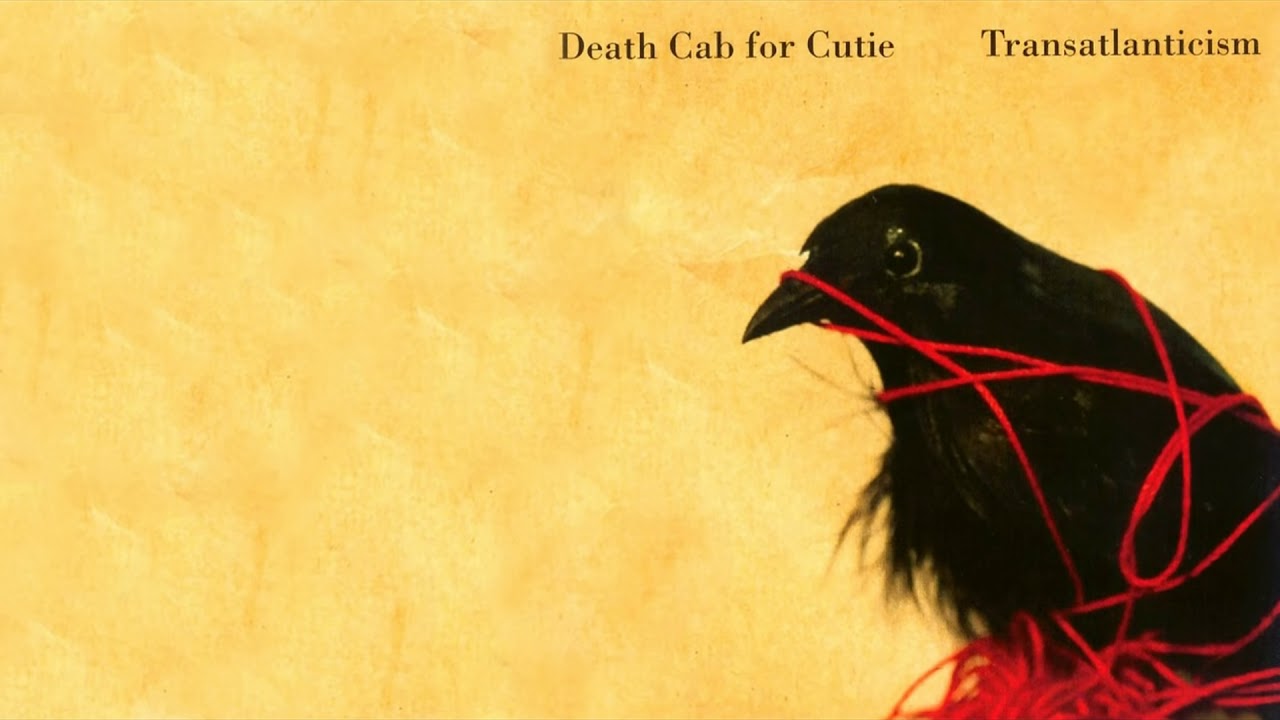

Featured Essay: There Are Break-up Albums and Then There’s Transatlanticism

by Steve McPherson

There’s a bit from comedian Stephen Wright where someone asks him how he’s doing, and he replies, “You know when you’re sitting on a chair and you lean back so you’re just on two legs and you lean too far so you almost fall over but at the last second you CATCH yourself? I feel like that all the time.”

By the end of December of 2003, I knew what he meant.

I was 27 years old and adrift, three-plus months out of a five-plus year relationship. Had you asked me a year before if I thought I’d be in it for the rest of my life, I would have said yes. The same went for the band I’d been in since high school, which was splintering into nothing after changing our name, firing our bassist, and losing our drummer.

I lived in Connecticut (first mistake) and I would move to Minneapolis on January 6. I had not yet exited the life I’d been living since college graduation, and I had not yet gotten into the life I would eventually settle into. There was no map, no guide for how to navigate this dead space. And it stretched aimless in front of me.

In the last three months I had shaved my head, then dyed my hair blond. I had gone on a few weak dates. I had seen my ex a handful of times as we tried to figure out if we were still friends. I had smashed things of hers I still had. I had taken a design class at Parsons and would be starting at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design soon.

I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing.

I played a New Year’s Eve gig with a different band at a high school auditorium in Montclair, New Jersey, and then headed back into the city to rehearse on the Lower East Side for another show on January 2. Before heading back to Connecticut (again, ick), I stopped at the Virgin Megastore in Union Square, near where my ex and I had lived a few years back. I bought a few CDs and when I got back in the car, slipped Transatlanticism by Death Cab for Cutie into the player.

I headed west on 15th Street and got on the West Side Highway with the late afternoon winter sun creeping down towards the Palisades. Over a gust of humming white noise, the album’s opening track exploded into crashing guitars for a solid 45 seconds before parting for Ben Gibbard’s opening lament: “So this is the new year / and I don’t feel any different.”

If you look back on your life as a listener, you can likely pinpoint the moments when music felt calibrated to your internal geography in an almost over-lucid way. The first time a song made you feel that flush of pinpricks on your neck or cheeks for a reason you couldn’t quite define. When the music was so loud and all-consuming and sweet at a concert or a club that it was less inside you than you were inside it. The moment when a song’s fury and anger made you see sparks and convinced you you could punch through a brick wall, just for a moment.

For the next 45 minutes, I was inside that feeling. I couldn’t understand it at the time, but now I see that it was not only working its way through my internal geography but remapping it. The album was beginning to make sense of this desolate stretch of my life by reflecting it back to me.

As I taped boxes back in my apartment in Connecticut (just, why), the album played on repeat through a shitty CD boombox, the bluntest lines leaving the tenderest bruises. “But there’s no blame for how our love did slowly fade / And now that it’s gone, it’s like it wasn’t there at all.” “Sometimes it seems that I don’t have the skills to recollect / The twists and turns of plot that turned us from lovers to friends.”

It was almost dreamlike, the sense in which every verse or chorus I turned down ended at a worn photo from my life. For three months, I’d been looking for a way out. Once things had started to fall apart, I’d tried changing everything. I tried to do it quickly. A new year, a new start. I wanted the power to forget it all.

What Transatlanticism gave me was a reason to sit inside it. To just fucking take it. Listening to the title track gradually unfold its allegory of a relationship undone by an ocean was excruciating and I couldn’t stop.

The rhythm of my footsteps crossing flatlands to your door

Have been silenced forevermore

The distance is quite simply much too far for me to row

It seems farther than ever before, oh no

The soft, forlorn panic of the way Gibbard sang the “oh no” before the endless futile spiral of “I need you so much closer” kicked in was gently overwhelming. As I played and replayed the album, the final snare hit of “Tiny Vessels” would cause my stomach to drop, anticipating the opening piano chords of “Transatlanticism.”

Slowly, as the packing continued and the snow fell and I readied myself for a straight-shot drive from Connecticut (good riddance) to Chicago alone, I came to understand that the real gift of the album was that it offered no exit or absolution. The closest it came was on closing track “A Lack of Color” when Gibbard sang, “This is fact not fiction / for the first time in years.”

What it offered, ultimately, was that thing we so rarely afford ourselves a sufficient quantity of: grace. When I wanted to run, it gave me distance. When I wanted speed, it gave me time. No date on the calendar was going to mark a clean break or a final chorus. But eventually it would fade, and Transatlanticism would be there until it did.

Decades later, I don’t know whether Transatlanticism is a classic album. I don’t even necessarily know if it’s a great album. What I know is that it was there for me when I needed it, and that might be rarer than greatness.

Steve McPherson is a musician and writer living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His writing about music and basketball has appeared in Rolling Stone, the New York Times, the New Yorker, Grantland and other publications. Follow him on BlueSky.