Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

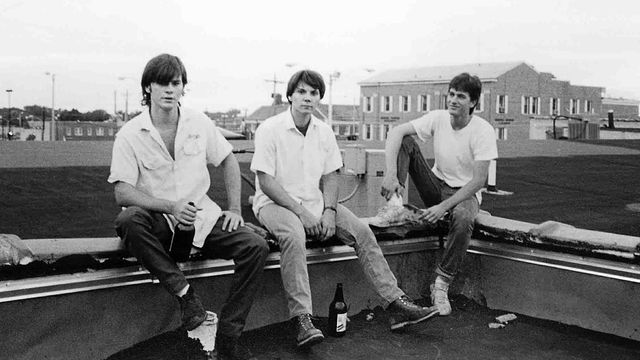

Featured Essay: There Was a Time - on Uncle Tupelo

by David Fenigsohn

A popular topic among any gathering of rock fans is the question: “Which act do you wish you could have seen in their prime?” Many of the usual answers—Jimi Hendrix, Queen, Nirvana—are informed by tragedy. These artists are chosen because they died before their devotees had the opportunity to see them. Not because as fans they weren’t clued-in enough at the time.

I had the opportunity to see my now-favorite band, Uncle Tupelo, in their heyday. They recorded their seminal debut No Depression in Boston, just a couple of miles from my dorm room in 1990, during which time I was the music editor of my college newspaper. The following year, they played Charlie’s Tap in Cambridge, a venue where I had seen several acts now faded from memory. By the time of their final tour in support of Anodyne, an alt-country masterpiece, in 1993, I was living in San Francisco and occasionally freelancing for a local music magazine. Their profile had risen—they had signed to a major label—but they still played Slim’s rather than the city’s more esteemed venues, such as the Warfield or the Fillmore. I didn’t go.

In 1994, the band imploded in a swirl of acrimony, resentment, and miscommunication between two of the era’s great songwriters, Jay Farrar and Jeff Tweedy. Both men quickly rebounded. Farrar formed Son Volt, and later that year, its debut album Trace yielded the biggest hits of his career. Tweedy formed Wilco, whose debut A.M. adhered closely to the alt-country sound, though they would later stretch their sonic palette and become one of the most critically acclaimed bands of the past twenty years.

It was the dueling yet intertwined albums that belatedly brought Farrar and Tweedy to my attention. In fairness, I was not alone. Uncle Tupelo’s best-selling album reportedly barely topped 150,000 copies. They were far too raw for country radio, but college radio didn’t play bands with banjos. They slipped between the cracks for many of us, even those who were paying attention.

I fell hard for Trace and finally saw Farrar live on Son Volt’s first tour. His voice was tuneful if not remarkable, but a perfect vehicle for his evocative lyrics and melodic, roots-driven rock. In concert, he barely acknowledged the crowd but brought a scruffy liveliness to the more polished sound of Son Volt’s album.

If Farrar was an enigma, Tweedy was the everyman. As part of Uncle Tupelo, his songwriting had perhaps been stifled. A.M. was just a preview of his talents. As a frontman, he branched out, eventually eclipsing his former bandmate in sales, fame, and critical acclaim.

But for me, both men’s best work was already behind them. The early nineties was a terrific time for new music, with nearly every week bringing fresh, exciting sounds—from the sweet oblivion of Screaming Trees to the low-end theories of A Tribe Called Quest. I already appreciated alt-country and had written about The Jayhawks around the time of Hollywood Town Hall. But in the influx of new records each week, I missed Uncle Tupelo until I retraced the origins of Son Volt and Wilco.

What I discovered, just a couple of years too late, was revelatory. Uncle Tupelo perfectly fused the urgency of punk with barroom poetry. Their best songs, spread across four albums in just a few years, gave voice to a uniquely Midwestern blend of hope, desperation, determination, and alcoholism.

Neither Son Volt nor Wilco perform many Uncle Tupelo songs. While in some ways regrettable, it is also understandable. Tweedy’s backing vocals infused Farrar’s compositions with an added element—a yearning and humanity otherwise absent even from his finest work with Son Volt. The most powerful example is “Looking for a Way Out,” their final original song from their last concert in St. Louis in 1994.

From their sophomore album Still Feel Gone, “Looking for a Way Out” is credited to all three band members (Mike Heidorn played drums), but it is unmistakably Farrar’s song. He belts out a vicious takedown of a dead-end life: “What has a life of 50 years in this town done for you / except to earn your name and place on a barstool?” On the chorus, Tweedy, looking impossibly young, nearly steals it away with his harmonies, his voice somehow perfectly meshing with Farrar’s despite the feedback, bar noise, and general mayhem of the band’s farewell concert.

All that was more than 30 years ago. I no longer regularly write about music. This site is dedicated to vinyl. Truthfully, while I still listen to Uncle Tupelo regularly, I confess I do so via streaming, despite owning one of their records, all their CDs, and, buried somewhere in a closet, a few cassettes. Now, without putting in anywhere near as much effort, I can be as up-to-date on new music as I care to be. If there were ever to be a new band I loved as much as Uncle Tupelo—which seems increasingly impossible, not only because of my age but because a new great rock band would be about as culturally relevant as a new jazz trio—the algorithm knows me well enough to bring them to my attention.

And in some ways, I can rejoice about that. Missing out on Uncle Tupelo when I had multiple opportunities to experience them at their best is my biggest regret as a music fan. But it somehow feels like cold comfort at best. Perhaps the answer lies in the lyrics to the chorus of that last song Farrar and Tweedy sang together so urgently:

There was a time You could put it out of your mind Leave it all behind There was a time That time is gone.

David Fenigsohn is a long-time music and culture writer. His work has appeared on RollingStone.com, PopMatters, and E! Online. He missed seeing Uncle Tupelo live but is always happy to share that one story about the time he interviewed Greg Allman.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal