WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: This is Big Audio Dynamite

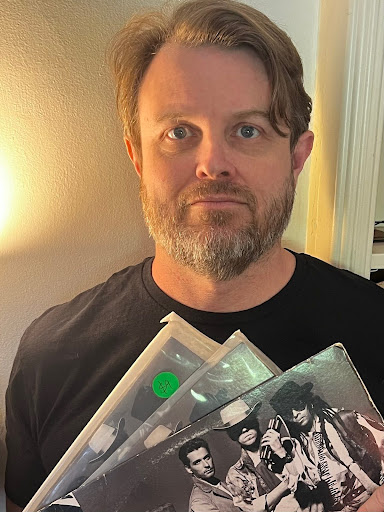

by Zak Berrie

I cannot stand to leave a copy of Big Audio Dynamite’s groundbreaking yet sadly underappreciated debut This Is Big Audio Dynamite (1985) in a bin of used records. It would feel like leaving a baby kitten unattended. My heart screams, “Where’s your momma, little guy? Why are you all alone?!”

I have five copies now.

In the summer of 1986, my teenaged older brother brought home the LP of This Is Big Audio Dynamite. He was a fan of The Clash and someone at a record store had recommended it. I was eight years old at the time. In hindsight, that is a helluva record for a kid that age in the mid-‘80s to listen to on repeat.

From its extensive use of samples, to the hip-hop beats and the rap-influenced vocals throughout, This… is a record that was happy breaking away from the pop music formulae that were popular at the time. No one is going to listen to the Side-One-Track-One Medicine Show and think that was made for MTV.

In hindsight, the themes of this record are wild. Medicine Show uses a sampled machine gun to blast alternative medicine grifters over twenty years before the founding of Goop. Sony mixes crass orientalism with a lament over American and British deindustrialization. E=MC2 is a love song to trashy Hollywood thrillers presented as a fever dream. Bottom Line has always read to me as a tongue-in-cheek sendup of the pop song formula from the same lineage as The Cure’s Friday I’m in Love from seven years later, but with a brilliantly programmed 808 rather than guitars.

And that takes us to part two, part two where we find A Party, a track that shows BAD’s clear lineage with The Clash. To the modern ear, the anticolonial social commentary is offset by tone deaf use of cultural stereotypes that Londoners of the 80s might have held about the developing world. It smacks of mockery in some places, but given how centrally the track features a sample of an institutional toilet flushing, a toilet that presumably was sampled in London itself, you wonder if they had meant to mock cultural stereotypes rather than perpetuate them.

If in 1986 I had been an elementary school kid with a wider knowledge of pop music, I would not have been surprised by this mix of social commentary and pop tunes, but in hindsight the connection to The Clash is clear. I didn’t get into themuntil embarrassingly late in my musical education. The first time I listened to London Calling (1979) all the way through, I remember thinking that it sounded as though BAD had a ska phase. Sure, kid, the same way that Nirvana sounds like a Foo Fighters side project with more distortion and less-coherent lyrics. It can be weird when you listen to music out of the chronology of its release.

Stone Thames, is a very early discussion of the AIDS epidemic that happens years before The Boss won an Oscar for The Streets of Philadelphia (1993), or Sir Elton John crooned The Last Song (1992), and a full decade before TLC warned global R&B listeners about bodies of water with unknown HIV status in Waterfalls (1995). Even George Michael, the undisputed king of selling gay themes to straight audiences, didn’t obliquely write about the HIV/AIDS crisis until You Have Been Loved in 1993. I suspect that the writers on the album, Mick Jones and Don Letts, were not concerned about being associated with homosexuality in the same way that Elton John or George Michael might have been in the mid-80s.

Filling out the flip side is Sudden Impact!, a fun groove which reads to me as an attempt to convey the vibe of the proto-raves that we know were happening in London at this time. The lyrics discuss confused teens and burnout cases sampling the latest candy deep in the woods. It’s all there. Sudden Impact! also includes Satanic Panic imagery that fits in with a theme of dissolute youth. I suspect someone in the band had a difficult trip at one of those parties.

The record closes with BAD, to form a perfect turducken of the use of that word. For me, this one has gone back and forth over the years from being a skip track to a favorite. It seems almost like the leftovers from the writer’s notebook splayed out to fill the last bit of time on the LP. Nowadays I feel like it’s the fun silly jam at the end of the session. Don’t ask too many questions, let’s just go to Florida and just have fun.

It’s difficult to trace the influence of This is Big Audio Dynamite, but it’s impossible to argue against the idea that it was one of the most important albums of the 1980s. It sold only around 700,000 copies globally, but clearly many of the artists who released music from the late 1990s onward listened to it.

To account for this delay, we need only look at the availability of audio sampling technology. BAD has never spoken in detail publicly about the studio technology that they used to make the record, so it may have been done using the widely available multi-track studio boards of the time. An audio engineer could create physical tape loops to record drum loops and long samples could be added simply by recording them to tape and hitting play at the right time.

These techniques had been around for some time. Studio savants Brian Eno and David Byrne released the sample and loop heavy My Life in the Bush of Ghosts in 1981. New Order is also known to have used mic stands and other random studio equipment to hold drum loops in the early 1980s. If that sounds difficult and error-prone, it was.

The music technology industry was working hard to build products to support the creative use of samples. Synclavier and Fairlight Instruments had samplers on the market in the 1970s but their tech was difficult to maintain and the cost of the units went from the tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars. E-mu Systems and Akai spent the 1990s perfecting the affordable sampler, playing a pivotal role in the creation of both hip-hop and electronica. By the late 1990s, affordable PCs and Macs could run software such as Steinberg’s Cubase VST or Emagic’s Logic Pro to use samples to compose tracks with the ease of an accountant filling out a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel.

Is it any surprise, then, that we didn’t first see sample-heavy creations topping the pop charts until the early 2000s? In some cases, though, the lineage is clear. I’ll give you an undeniable example: Give me the name of the innovative London-based pop band that seamlessly integrates elements of hip hop and dance… and that also features Mick Jones? Do I mean Big Audio Dynamite or Gorillaz? Yes.

As we approach the 40th anniversary of its release, have a look through the used bin at your favorite record store. You may rescue the beautiful musical kitten that is an LP of This is Big Audio Dynamite.Unless, of course, I adopted it first.

Zak Berrie is a rizz worker in tech from Southern California. He has long collected music and has DJed since before the sync button was invented. He posts his mixes at https://soundcloud.com/zak-berrie-949921416.