WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Nate Patrin on Traffic's "The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys"

by Nate Patrin

One of the things I miss the most about my early years of crate digging was the thrilling feeling of displacement I felt every time I stumbled across an unfamiliar old secondhand LP with an unconventional sleeve. I’m not just talking about the artwork, but the very structure: the elaborate fold-out explosions of Isaac Hayes’ audaciously messianic Black Moses or Hawkwind’s psych-modernist Barney Bubbles concoction X In Search of Space; the die-cut oddities like the octagonal Rolling Stones comp *Through the Past, Darkly (Big Hits Vol. 2)*or Cheech & Chong’s secobarbital-shaped Sleeping Beauty; and in its most elaborate form, the futurist sci-fi puzzle box of Gil Mellé’s beautifully unnerving experimental synthesized score to The Andromeda Strain.

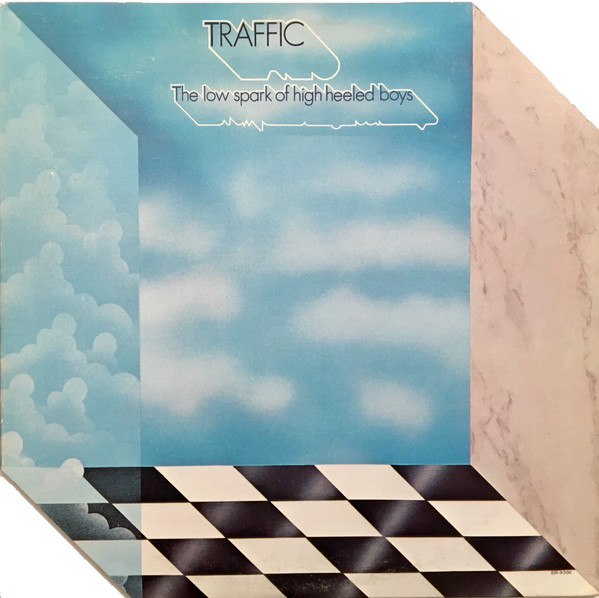

And yet it’s one of the simpler examples that’s stuck with me the most – a design now inseparable from my relationship to the music it houses. The sleeve for Traffic’s 1971 LP The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys is arresting in its design. It’s simple yet surreal, vivid yet enigmatic, a sort of pop-art trompe l’oeil that attempts to bend the two-dimensional flatness of a record cover into a curious 3D cubespace that flirts with MC Escher perspective tricks in a subtly disorienting way. Maybe the best gag in this design is that the artist/title script up top, rendered in a skinny echt-’70s mod font, is also outlined in a three-dimensional space that runs perpendicular to the cubic illusion yet seems to sit at an opposite angle to it, retreating into a background that appears askew from the orientation of the rest of the composition.

The period-popular stylization of Airbrush Surrealism is in full effect here, too; there’s a vivid contrast between the hazy, naturalistic cloud wisps in the background and the billowy, rounded, cartoonish formations on the left side that seem to reflect them as caricature. The other prominent aspect of the album’s design is a quasi-architectural detail – a marble wall adjoining a black-and-white checkered-tiled floor – that could evoke the lobby of an office building or a department store or a bank or a castle. It’s a contrast between built space and the omnipresence of the atmosphere outside and up above, cordoned inside a boundary that seems claustrophobic and spacious all at once. Maybe that’s a too-elaborate analysis of art meant to shroud a record featuring such titles as “Rock and Roll Stew” and “Light Up or Leave Me Alone,” but I figure it’s not too pretentious to venture into this kind of theorizing considering the thing’s in MoMA’s collection.

And the funniest thing about this cover? The die cut on the upper-right corner sabotages the industry tradition of snipping off that particular part of a traditionally square 12" sleeve when a remaindered, low-selling album is bound for the cutout bin. I bet discount retailers hated that.

This sleeve was the first major record cover design gig for Tony Wright, who would become one of Island Records’ premier in-house artists. Low Spark isn’t his sole MoMA entry; the flat-yet-vivid sleeve he designed for the B-52’s ‘79 self-titled is in the collection, too. And every reggae fan either owns or is negligent in not owning a host of legendary records Wright also designed and illustrated the sleeves for: Bob Marley & the Wailers’ Natty Dread, Max Romeo & the Upsetters’ War in a Babylon, Lee Perry’s Super Ape, Junior Murvin’s Police and Thieves, and Third World’s 96° In The Shade rank among the most notable. Throw in some choice odds and ends from other genres and scenes – the Meters’ classic-singles comp Cissy Strut, MPB great Jorge Ben’s joyous samba-disco Tropical, John Martyn’s artfully zooted dub fugue One World, Suicide’s synthrock panic attack Suicide: Alan Vega - Martin Rev – and you’ve got a combination of visual ingenuity and discographic excellence that stands up next to contemporaries like Hipgnosis, Shusei Nagaoka, and even John Berg.

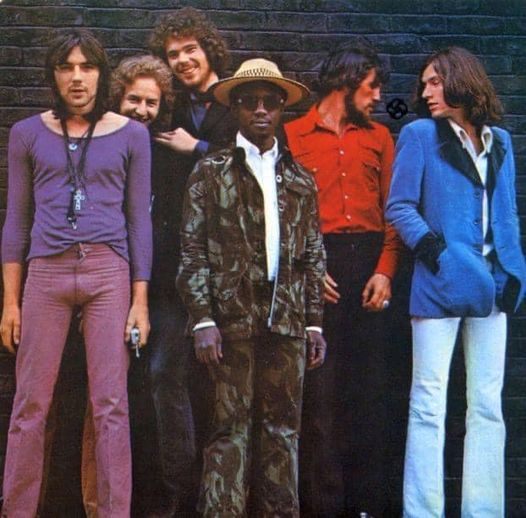

But the question remains: what does an album in a sleeve like this sound like, and what kind of band would concoct it? Flip the LP over and the photo on the back and you’ll see an incarnation of Traffic that was drastically shaken up from the one that made their name in the late ’60s psychedelic scene. From the original lineup, that’s sax/flute player Chris Wood on the left in the provocatively fitting pants, while the right side of the photo features drummer Jim Capaldi and frontman/keyboardist Steve Winwood engaging in what looks like a distracted conversation. Ghana-born percussionist Anthony “Rebop” Kwaku Baah is the guy with the two-decade headstart on Goodie Mob camo chic. And the cheerful-looking fellas behind him and Wood are bassist Ric Grech, who’d followed Winwood from the burned-out husk of stalled-out supergroup Blind Faith, and session drummer Jim Gordon, who was in the midst of appearing on about 50 different rock records worth owning between the mid-’60s and late-’70s before committing one of music’s most troubling “separate the artist from the art” tragedies.

Itinerant guitarist Dave Mason had been a sporadic enough member of the group that they could technically be considered a trio-plus-one for their ’60s come-up, but they sprawled out a bit after a decade-straddling cycle of disbanding and reforming. Winwood conceived of 1970’s John Barleycorn Must Die as a solo record that became a Traffic reunion once he realized Wood and Capaldi still made good collaborators. Then he brought on Grech, and recruited Gordon and Rebop to make up for Capaldi’s reduced role in the band as he dealt with the sudden death of his infant son to SIDS. This lineup cut a live album, 1971’s Welcome to the Canteen, that’s most notable for turning two of Winwood’s early radio hits – “Dear Mr. Fantasy” and Spencer Davis Group’s “Gimme Some Lovin’” – into roiling jam sessions conversant with post-psychedelia’s increasing enthusiasm for soul-jazz and Latin rock.

And it’s that mode that makes Low Spark so fascinating to me. Granted, I enjoy all that “why punk had to happen” music from the early ’70s – self-indulgent soloing and jazzbo experimentation and shameless attempts by rock’n’rollers to incorporate funk and R&B. (“Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” is still one of my five favorite Stones songs, for God’s sake.) But I heard this album for the first time as a teenager in the mid-’90s, when I was spending half my time listening to contemporary alt-rock, hip-hop, and dance music, and the other half indulging my record-geek classic rock fascinations, so my tastes were already getting kind of tangled and contradictory. I picked up my first copy of this album at the same St. Paul Cheapo Records location where Hüsker Dü’s Grant Hart had worked decades prior, and listened to it on a hand-me-down Zenith Allegro radio/turntable console while wearing a pair of massive, beige,’70s-era headphones for that period-accurate experience (at least in auditorily; I was not connected to a good source for schwag weed or reds).

So I’d spend some curious mind-wandering late nights sinking into an album that came out six years before I was born and finding things in it that I wasn’t hearing in too many other places. In retrospect it’s the kind of thing that made my eventual enthusiasm for Steely Dan seem like a foregone conclusion: Traffic’s jazz-rock plays here like a more idealistic (if often frustrated) shaggy British progenitor to Walt and Don’s more sardonic and meticulous engagement with the form. Wood’s flute playing lends a mellow pastoral cast to the folky groove of “Hidden Treasure,” the hippie-Stevie yearning of “Many A Mile to Freedom,” and the shapeshifting country/blues/psych/fusion of “Rainmaker,” and while I don’t click with those songs like I do with the rest of the album, I do like them enough to acknowledge that the effect is a lot closer to Yusef Lateef than Jethro Tull and thank goodness for that. There are also the two radio-ready cuts sung by Capaldi, which sound kind of like War fronted by someone working through a lot of personal exasperation. The Gordon/Grech-penned “Rock & Roll Stew” is one of those songs about how the touring life means having to figure out how to deal with being bored out of your mind on the road, while Capaldi’s own “Light Up or Leave Me Alone” is louche gripe about some social-setting energy vampire fully intent on wasting his time. (Its target is apparently a woman of vague provenance – “the skirt that you’re wearing is way past your knees” is the sole detail shared.) Pretty solid stuff, a couple of strong jams and nothing that’d make me reposition the needle.

Yet nothing hit me quite like the title cut did. In immersing myself in this odd corner of a vividly rendered yet long-dated aesthetic of an older and increasingly unfashionable generational touchstone, I gravitated toward the longest cut on the record, and got deeply and thoroughly lost inside it. Its title is an enigma, a phrase conjured up by actor Michael J. Pollard (C.W. Moss in Bonnie and Clyde), and alternately interpreted as referring either to proto-glam countercultural gender-nonconformists or organized-crime hitmen (or, according to some dart-throwing speculator on Genius, some sort of narcotic reference). But the song’s execution is driven by a strange duality. It’s almost the musical equivalent of the illusion on the cover: it fades in to a meditatively paced piano-driven riff that could be called a dirge if it wasn’t so light-footed, while Rebop’s conga, Gordon’s fills, and the first of Wood’s hazily awed sax solos pulling you along into a velvety, alluring sense of disoriented ennui. And yet when it gets to the hook, it’s damn near as simple as rock and roll gets – all hammered piano chords that you can trace back to Fats Domino and terse emphatic two-note sax exclamations snapping you out of your fugue until that wandering quietude returns to reclaim the atmosphere. The keyboard solos themselves are a study in contrasts, too – the piano is graceful and poised, but there’s also this sharp, piercing whine-buzz of a counterpoint via a Hammond B3 run through a fuzzbox that sounds like a huge and unwieldy yet luminescent insect. There’s this oddly intense yet calming push-pull between energetic nerviness and placid contemplation that gives a nearly 12-minute song the feeling of something much more dynamic and startling than your typical half-a-side-filling jam-sesh workout.

As for the lyrics, those words did plenty to wash away my earlier association between Steve Winwood’s voice and the beer commercial mersh I endured as a kid. While it’s probably noteworthy to point to “The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys” as an early contrast to a bummer sellout arc that would later betray its own message, the lyrics provide this other aspect to the song’s duality – a balance between cynicism and hope – that informs its odd blend of abstraction and to-the-point simplicity. And you just can’t escape from the sound is the threat, don’t worry too much, it’ll happen to you the serene acceptance. The chorus sets a “you” (or the singer himself) up for a fall – yet another victim of a capital-over-art business model that screws over musicians while “the man in the suit has just bought a new car / From the profit he’s made on your dreams” – only for some mysterious counterforce sweeping in to take that threat out. It might disturb you, might make you reevaluate your path and what your next move might be, but in the end you’ve got to ask yourself whether you’ll remember how that conflict plays out and whether you’ll ever wind up participating in it yourself. “If I gave you everything that I owned/And asked for nothing in return/Would you do the same for me as I would for you?” is as simple a moral a question there is, and yet Winwood sings it like it’s still a revelation. Maybe, for an audience that had likely been pulled through a gauntlet of disillusionment during the previous several years, it still had to be.

Sadly, it feels like the returns diminished, at least when I set out trying to find out where they went from here. Traffic cast off Grech and Gordon, had a stint where a few alumni of the Swampers bolstered their ranks, and released a few albums that reiterated the Low Spark sound to increasingly ambivalent effect. (Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory even kept the same die cut cube concept for their Wright-illustrated cover, but that just made it look like a water-treading sequel.) Winwood battled the life-threatening abdominal condition peritonitis, Wood fought with substance abuse and depression, and the group broke up after a frustrated, ulcer-wracked Winwood walked off mid-concert during an October ‘74 show in Chicago. For the most part, even though Low Spark was a pretty decent-sized hit in the States, they seem to have failed to make the influential cross-generational music-head leap that peers like Steely Dan, Fleetwood Mac, and Joni Mitchell earned. Still, you can still hear their traces if you search carefully enough. Sometimes you just have to let your perspective play tricks on you.

Nate Patrin is a native of St. Paul, Minnesota, who has been writing about music and its role in culture for over two decades. His work has previously appeared in sites and publications including Pitchfork, Stereogum, Bandcamp Daily, City Pages, Maggot Brain, The Shfl, and many more. His first book, Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop, was published by University of Minnesota Press in 2020. His second, The Needle and the Lens: Pop Goes to the Movies from Rock ’n’ Roll to Synthwave, was also published by University of Minnesota Press in 2023, and has been nominated for a 2024 Minnesota Book Award. He can be found on Bluesky at @natepatrin.bsky.social