WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Two Gifts And A Life

by Warren Senders

My high school classmates were listening to the J.Geils Band, Led Zeppelin, the Stones. At fifteen, younger than everyone else in sophomore year, I was way out on a musical limb, filling my ears with Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, and a Cripple Clarence Lofton record I’d found on sale for a nickel(!) at my local library, which opened with “I Don’t Know,” a ten-bar blues that programmed me for the truncated form like a Greylag goose fixating on a naturalist. While my choices may have begun as a response to my peer group’s tastes, the pleasures of the unfamiliar became central to my identity.

During Junior year, I befriended the late-night jazz DJ on the local public radio station. Steve started his show at 11 o’clock and continued into the wee hours. A lonely night owl, I began calling with requests and comments, and we started a conversation that has continued to this day. During a school vacation week he said, “why don’t you come into Boston, meet me at my office, and join me for lunch?”

His day job was at the Schwann Record Catalog, a music retailer’s publication that listed new LPs released in the United States every month. Record companies sent copies of the new products to Schwann for cataloging, which meant that when I arrived at Steve’s office, he shook my hand, beckoned to a long wall of shelves full of LPs, and said, “Help yourself.” Since he (understandably) took all the jazz, and I wasn’t interested in the pop or the classical, what remained for my investigation and predation was music from America’s weirdest fringes (steam calliopes, abstract spoken-word collages, and the like), or ethnographic field recordings from pretty much everywhere, released by Nonesuch Explorer, Folkways, and Lyrichord.

I loaded up about 50 records and took ’em home after lunch. My musical xenophilia accelerated after I graduated in 1976 and took a Somerville apartment with friends. Coltrane and Sun Ra shared my turntable with Turkish village dances. I met Steve regularly, and occasionally he’d save a disc for me, like Paul Berliner’s recordings of Zimbabwean Mbira music, or “Ravi Shankar’s Music Festival From India,” which included some singing that set me searching for an Indian vocal teacher (I succeeded, beginning lessons with Kalpana Mazumdar in early 1977).

One day he called and said, “I was on vacation in Europe, and I got you something.” He came over for dinner, bearing the original Italian EMI release of Don Cherry’s “Brown Rice.”

Midway through the ecstatic trumpet/bass/drums trio of “Malkauns” he turned to me and said, sighing, “I could listen to this forever.” Me too. I listened to that record a lot.

And then Lester Bangs hurt my feelings. Seriously. The great gonzo rock critic had embarked on a strange digression in the pages of the Boston Phoenix, hurling undeserved insults at “Brown Rice,” an album way out of his wheelhouse. I wrote a letter to the editor, decrying Bangs’ ignorance of Cherry’s oeuvre, and they printed it.

Shortly thereafter the phone rang. The voice at the other end said, “I read your letter. I’m Tommy K___. Can we meet?” A few days later Tommy — a skinny guy with short hair a few years older than me — came to visit, and after we’d spent the afternoon listening to records in my untidy apartment, he said, “I have something for you. I’ll bring it tomorrow." The next day he handed me three LP records in a brown paper bag. “You’ll enjoy these,” he said, and left. I never saw him again.

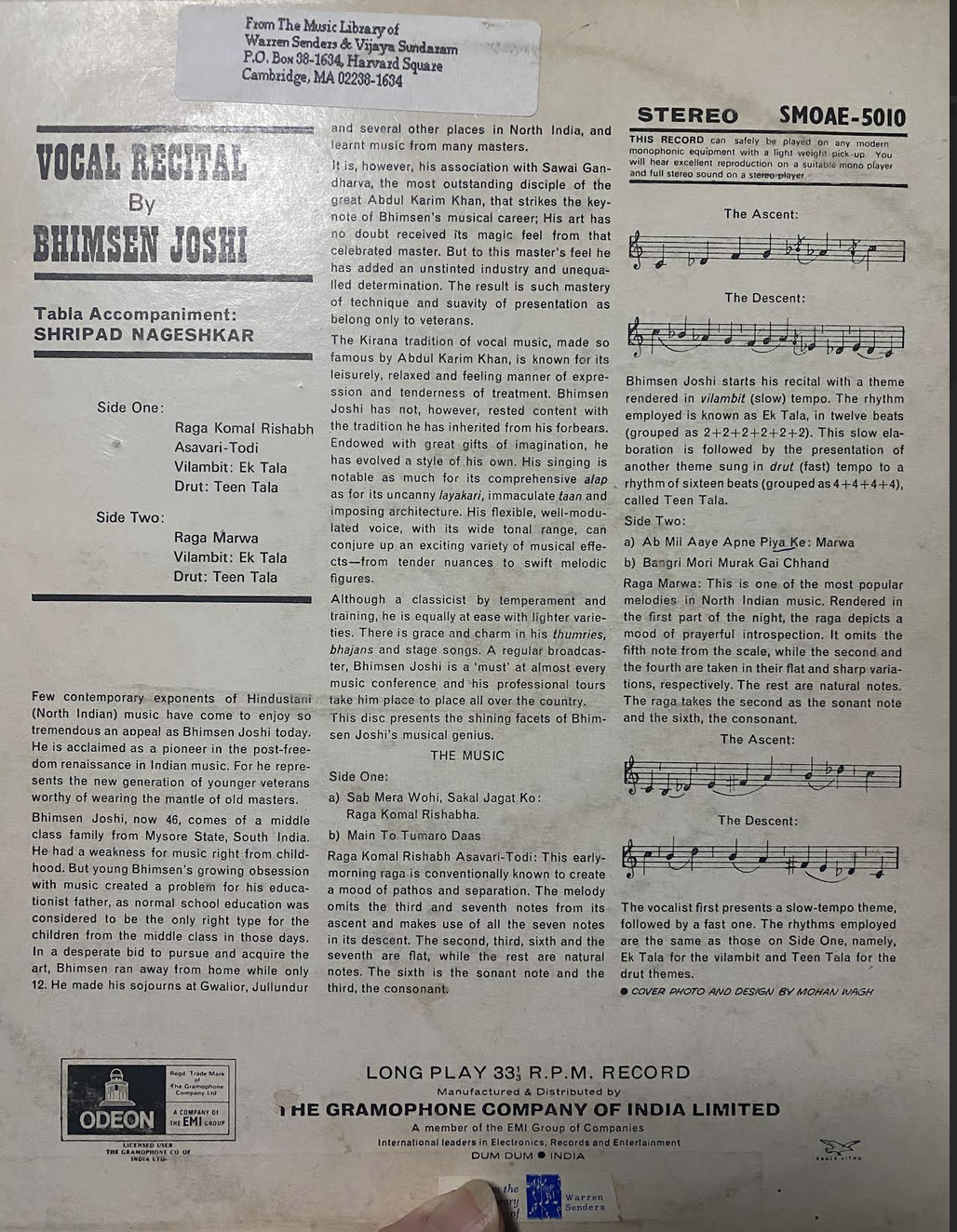

I was 19 and had just started studying music seriously, taking lessons in jazz guitar and Hindustani vocals. Tommy had brought me three classic LPs of raga singing — made in India, pressed on gritty vinyl, rich in both surface noise and the spiraling overtones of the tamboura drone.

The Dagar Brothers (specifically, I’d later learn, the SENIOR Dagar Brothers, because there was another pair of brothers of more recent vintage) sang in an old style called dhrupad, their eerily perfect unisons underpinned by a restrained thunder from the accompanying drum. The disc’s hole was the tiniest bit off-center, giving the proceedings a vertiginous quality. My beginner’s understanding was so rudimentary, I couldn’t follow the flow of events at all. But I played it over and over, gradually tapping into the performance’s inner logic despite my lack of vocabulary.

Prabha Atre’s disc was charming. Her voice, even to my untrained ear, was exquisitely in tune. The B side opened with one of the catchiest tunes I’d ever heard, and when she was improvising, the flow of her variations was easy to catch. Almost fifty years later, I still use this recording to introduce people to Hindustani song.

But the Dagar Brothers and Prabha Atre didn’t prepare me for what was coming up next.

The back cover had many words, but none of them made any sense at all. I love puzzles and rabbit holes, but this was 1977; there was no internet. My few months of singing lessons were all focused on keeping my voice steady (no easy task); my teacher gave me no theory or terminology.

I put the disc on the turntable and lowered the needle.

Well, damn. This was improvisation undertaken with more daring than any other musician I’d ever heard, including Ornette Coleman. Whoever he was, Bhimsen Joshi was no ordinary singer. There was serious crazy at work here, combined with an inner rigor that kept things from going completely off the rails.

Most of my friends from youth group were into the Grateful Dead (peace be upon them), Joni Mitchell, or some other facet of the white hippie scene. A few people knew a little about jazz, but nobody from my peer group was ready for Bhimsen Joshi. One or two called it “soothing,” which puzzled me; all I could hear were the juddering, multi octave melodies, sometimes careening to an obvious resolution, sometimes just…hanging there in mid-air. Not soothing at all; I thought this guy sounded possessed.

I’d go into used record stores and buy any piece of Indian classical music I could find. I learned to avoid Indian pop music, mostly film soundtracks that didn’t scratch my itch. Once or twice I found another Bhimsen Joshi record, always on the same substandard vinyl that attracted clicks, pops, and scratches like an overripe banana draws fruit flies. Once I went to the “world music” shelf at Looney Tunes in Boston, located the plastic divider labeled “India,” and found “Sounds of The Indianapolis 500,” a disc of racecar noises. To this day I regret not buying it. Ahem.

By the late 70s Boston was developing an actual Hindustani music scene. I made myself useful to the concert organizers, helping with mailing lists, posters, and the make-work of event production. I started meeting musicians, finding books, journals, and liner notes that helped me grasp the music’s form and history.

I read about Bhimsen Joshi’s spectacular vocal feats; his flamboyant gestures while singing; his bouts of public drunkenness; his turbulent personal life — and his insane concert career: in the 1960s he gave over 400 3-4 hour concerts a year (film of a 1971 concert: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RqwE6K8Dy-g). I learned that he was still alive, still performing, roughly my father’s age. In 1982 he came to Boston, and a friend joined me for the concert, but she left at the interval, claiming a headache (Bhimsen strikes again!). Nothing could have budged me; he was in great shape, sang brilliantly, and the atmosphere was very exciting.

By 1983 or so I could mostly make sense of the notes on that disc, and I’d built a collection of my own. Indian music collectors make dedicated Grateful Dead archivists look like well-meaning dilettantes. The recorded history of Indian music goes back to 1902, and includes black swan phenomena like the maharaja who decided — in the 1930s! — to buy an actual record lathe in order to record the concerts he hosted in his palace. Cassette recordings of great and middling artists alike were in wide circulation, acquiring a fresh patina of hiss with every duplication. I particularly liked tapes of broadcasts on All India Radio, which had an unmistakable sonic ambience.

In 1984 I acquired Bhimsen Joshi’s address and wrote, asking him to take me on as a student. After some back and forth, he agreed, and with grant funding I finally arrived in Pune, Maharashtra in September, 1985. He lived with his second wife and their three children had a bungalow in a relatively upscale neighborhood, sheltered by a masonry wall that blocked much of the traffic noise. I was very nervous when I went in for the first time.

Although he and his family were kind to me, my studies with the Great Man weren’t what I’d hoped for. While I went every day to his house to practice in hopes of getting a lesson, he was not a teacher, and especially not a teacher who could work with someone from outside the tradition. I met some of his students and was mostly not impressed. The Indian proverb, “in the shade of a great tree, nothing grows,” held true in that stressful ecosystem. Bhimsen no longer drank (thanks to his wife, who kept the mercurial genius on a short lead), but the household had a depressed and apprehensive mood, and time spent there made me deeply unhappy. He was often surrounded by overeager admirers who praised him extravagantly — while imitating his singing badly — and that certainly didn’t help.

Occasionally he would invite me along on a road trip to an out-of-town concert. Once it was to the governor’s mansion in Mumbai, where we were pampered, cosseted, and fed a lavish supper after the concert. Another time we went to a tiny town in Karnataka, the neighboring state to the South; I spent 18 hours in the back seat of his 1963 Mercedes, the car full of family, playing the strangest round of “antakshari” ever (it’s a singing game, where player 2 sings a song which starts on the final phoneme of Player 1’s choice, and so on. It’s usually done with Bollywood songs, none of which I knew; my contributions were mostly drawn from my childhood summer camp repertoire. As I said, strange.)

The music still captured my imagination, and I was going to concerts several nights a week. Sometimes these were in auditoriums, but often and more satisfyingly in cramped dusty rooms, flyspecked portraits of musicians from the last century hanging on the wall, their frames hung with garlands of dessicated flowers, the ceiling fans adding a percussive tattoo to the fluorescent tubelights’ electronic hum an irrational interval away from the tambouras’ pitch. I’d leave my sandals in the pile at the door, sit cross-legged on threadbare carpets as close to the front as I could get, and pay as much attention to the audience members as to the singer. A lot of them were in their eighties. As the music unfolded, they commented constantly on what the musicians were doing, in Marathi, Hindi or English, offering praise for the good and polite euphemisms for the bad. One gentleman showed me his concert diary, in which he’d recorded in tiny Devanagari letters the particulars of every concert he’d attended since 1951. He could say with authority that he’d heard the singer’s father present the same piece in (checks notes) 1967. These were deep listeners.

After months of frustration, I eventually found a teacher who did know what to do with me, and began studying the singing in real depth (lessons with my actual teacher, Pt. S.G. Devasthali, can be found here). I lived in India for about 6 years, studying and eventually performing. The more I learned, the more I loved; the music continued to hold me in its sway.

In 1986 I met Vijaya Sundaram, who became my wife (we’re still together after 37 years). I made my professional debut as a Hindustani singer in Delhi in 1990, and over the years I grew away from my original Bhimsen fanboi stance to a more nuanced awareness of the man’s greatnesses and weaknesses. I met Prabha Atre and the surviving member of the Senior Dagar Brothers, and had a chance to thank them in person. I now have lots of LPs (and 78s, too!) of Hindustani singing. The ones from India don’t have printed spines, which means I have to recognize them by the precise patterns of wear and tear on the cardboard sleeves. I make my living singing and teaching this music. I’ve written liner notes that (I hope) make more sense than those I scratched my head over in 1976.

Sometimes it all seems too utterly improbable: the whole arc of my musical life, set in motion by two gifts. I still talk regularly with Steve, though not as often as I’d like. Tommy K___? His last name was written inside the three lps he’d left with me in 1977, and I eventually tracked him down in a Pittsburgh suburb about twenty-five years ago.

“I remember you,” he said when I identified myself. “I’ve followed your career.” I offered to return the records, but he told me to keep them.

Warren Senders is an internationally recognized musician and educator with decades of involvement in the artistic and pedagogical traditions of India as well as those of Western, African and African-American musics. (www.warrensenders.com)

Also trained as a jazz bassist, he founded the pan-cultural ensemble Antigravity in 1981; the group’s two CDs have received raves from music critics all over the world. As a teacher, he is a dedicated advocate of experiential “learning-by-doing.” As part of his work with the Music-in-Education faculty at New England Conservatory of Music, he has developed curriculum initiatives in which music from many cultures is integrated into the pedagodical process in subjects as diverse as poetry, history and art. An expert on the stimulation and nurturing of individual creativity, Mr. Senders is on the faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies at New England Conservatory of Music and has held teaching positions at the University of Vermont, Emerson College, Babson College, Berklee College of Music, and the Museum School of Fine Arts.

He is a dedicated climate activist with a long history of engagement in the struggle for environmental justice, including his work on the environment/music podcast, “Cool Tunes For A Hot Planet.” (https://cooltunesforahotplanet.com/)