WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Featured Essay: Word Begets Image

by David Kane

“Word Begets Image, and Image Is Virus.”

I first heard those words on a CD called The Elvis of Letters, which I snatched for ten bucks from the old Amoeba Music on Sunset. I had made a habit of buying cheap discs in the hopes of jolting myself from a funky rut characteristic of one’s early twenties. My consciousness felt petrified, rigid, inflexible. A scaffolding had been built around my brain, directing my feelings into prescribed patterns with no real agency. I was not in control of myself. Being a young man in crisis, I turned to psychotronic media, hoping to reprogram my mind into a shape I’d be proud to call my own. Like most risky substances, William S. Burroughs sure gave me a jolt.

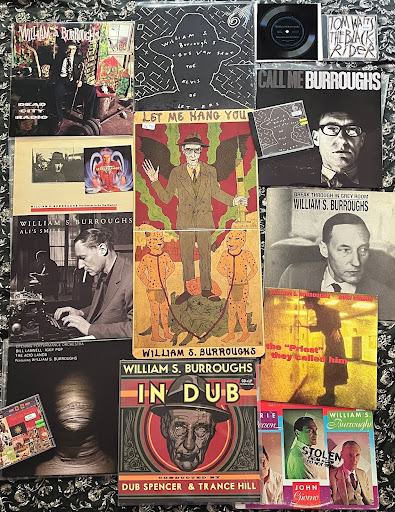

For The Elvis of Letters, filmmaker Gus Van Sant remixed material from Call Me Burroughs, the author’s first audio project from 1965. These albums are separated by two decades. Seven years after buying that CD, I nabbed the vinyl version, bolstering a collection of over a dozen items featuring the old man’s voice on wax, oftentimes mixed with music. By then, I was hooked.

William S. Burroughs was a beat poet and author, infamous for his impact on outlaw literature. Drugs, sexuality, violence, mutation, ripping satire of Western culture in all its influence, from the suburbs to the syndicate board rooms. He excoriated the horror with a cool detachment we wish we could muster. My opinion of the man himself changed as I sunk deeper. I’ve regarded him as a mapmaker of psychic landscapes, a mythologian of the space age, a pretended worker of miracles, an unrepentant lunatic, and so on. Ultimately, he spins a good yarn, and that’s all a writer needs to do.

If one requests a place to start with Willy wax, I say you can’t go wrong with the trilogy produced by Hal Wilner: Dead City Radio, Spare Ass Annie, and Let Me Hang You (the first Burroughs vinyl I acquired). They feature selections of spoken word (recorded in 1988 & 1989) set to various musical styles, from symphonic backlogs to bespoke funk. All three albums are fantastic, really showcasing the wide ranging profundity of the author’s writing. Seek out a listen, but bring a mop—things get sticky.

My exploration was circuitous. I did not sit down and chart a discographic course. I let the vibrations waft my way, like a summer breeze ferrying the fishy stink of the sea. When I visit record stores, I go to the spoken word section and ask for Burroughs by name; this has garnered three pieces of my collection. One cat said he regretted selling his copy of The “Priest” They Called Him, a rare collaboration between W.S.B. and Kurt Cobain. I sniffed out a copy immediately. Yes, I’m bragging. Every collector knows the pride of swallowing the tough stuff. Like junkies, we lick our lips over the immaculate fix.

Burroughs talks with the weight of heavy power but swings easily into comical lightness. His voice can be studiously stern yet scatalogically silly, all simultaneously. He’ll narrate a quiet story about a desperate junky on Christmas Eve, then gracefully pivot into a war journalist’s psychographic spasm from a telepathic battlefield. The funny stories are hilarious, the gross stories gut-wrenching. His theological pontifications chase God through the eye of our anal gland. He rebukes God Himself, mocking the very thermodynamic laws that would govern His supposed rule. Burroughs balks at all human claims of ascendency to power, naming it what it is: an uncontrolled infection driving our species to self-destruction.

There is something sad about the voice, a mournful dirge for a lost world of possibility; also something of joyous frivolity, speaking just for jollies. All of it contained within a cadence of seemingly detached irony. But you can hear the emotion beneath the croaky paroxysms. Spitting truth, they call it.

I listen to Burroughs when I’m upset. I get very angry and dispirited by the world, the people in control, the people out of control. There are records that make me feel sick, and yet I listen, enough times to drown in nausea. Up to my eyeballs, I realize the sickness doesn’t originate in the words; it’s in the world. The disgust is binding the very air molecules sucking down my throat. This disease predates me, and the records are scalpels for dissecting viral agents. Maybe if I keep digging into the grooves, I’ll taste the bottom, a suboceanic realm of muck. Maybe I’ll finally stomach it. Metabolize it. Shit out the world, instead of feeling it shit me out.

Somehow Burroughs’ work makes me feel better, even though much of it is ugly. His word hoard opens, and out sluices naked sewage from the gutterful human subconscious. That’s what makes it hard to listen to: it’s true, like a debauched autopsy. You see all the guts hanging out of our underthings. Junk you’d like to forget, but you know you’re the better for knowing it. The truth is beyond ugly and beauty—it’s a slimy sublime.

Years after having started on this track, the question is of course, did I get what I want. I didn’t feel in control, so what do I feel now? I repeat my cycles. I follow my script and feel the same dull insect satisfaction of biologic protocol. And yet, at times, I float away from the track and watch my body chug along. Often I hear William’s voice, unbidden, in my head. The cadence comes from deep in the throat, burped from some primordial sonic bog, presenting the words as a gravid load to the ear canal. I see the world the way he weaves it. With Bill’s gift, I’m able to ruminate on the concept of freewill. I turn it over in my mind, like a bovine cud-chewer. I spin the scalpel, pry loose, and let go. I melt into the word and find myself reiterated by its syllables. I credit this collection for suturing my nervous system into untraceable shapes. I have learned to respect the mystery. Worship it, even. I even created a clown character Dr. Bendigan that is inspired by Burroughs’ Dr. Benway. How’s that for worship?

We are all recordings. These very words, echoes of myself, of as much substance as dead skin cells etched into my bed sheets, find you in an after-thought.Come find me in my phantasmal filth. Find Uncle Bill there too, seated in the booth, sucking a green syrup and waxing poetic on the gifts of the divine sphincter. Welcome to the broth where we all end up, inevitably slurped down by the next generation of souls. You’re nowhere except right there right now, dear reader. None of those images is you. None of these words is me. Nothing here now but the recordings—switch the machine off.

Word begets image, and image is Virus.

David Kane is a writer & performer living in Los Angeles. He has published fiction, poetry, and comics in Cosmic Pulp Zine. He has written essays for Exploits Magazine, psychopomp.com, and Beauty of Horror. He produces original absurdist theatre, frequently performing as his character, Dr. Bendigan. David’s collection of strange tales, Drippy Trippy Doom, is available to purchase here. You can find more of David’s work at doompunkdispatch.com.