WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

45s of my Youth: Teen Tragedy

by editor Michele Catalano

What you consider to be entertaining at 12 or 13 is generally not what adults consider entertaining. Subjecting family members to my idea of entertainment was a hallmark for me at that age. I regaled them with dreams (they pretended to fall asleep while I described these dreams in great detail). I read them passages from books I was currently reading. I made them come into the living room to watch what the Banana Splits were up to. Because I found these things amusing, I expected my parents to feel the same way. This was not always the case. They tolerated the dreams and books and TV show snippets, but when it came to me actually providing the entertainment, they drew a thin line.

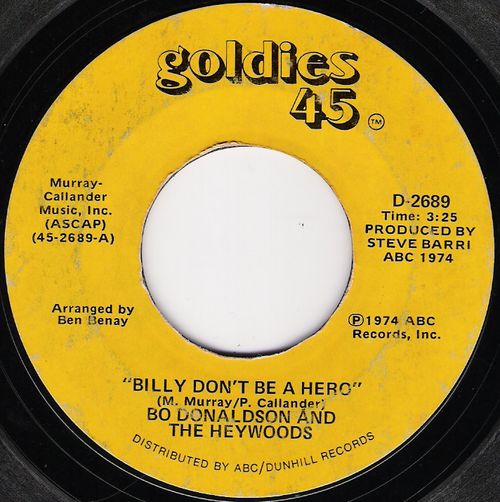

It’s 1975. My cousins got a new record player, and we set it up in their finished basement. They also got a stack of 45s. We set about listening to them all; familiar songs often played on WABC, the AM station we listened to at the time. It was fun to play the songs on our own, without having to wait for them to come on the radio. Some tunes we played over and over again. Some went into a pile to be forgotten. There were two specific songs that had captured our attention over the previous year: “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero” by Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods and “Run, Joey, Run” by David Geddes. We played them endlessly, losing ourselves in the narrative of each tune, learning all the words, stopping and starting on certain parts.

“Billy” is about a boy who enlisted in the Army to fight in a war. Just what war is never specified, and though legend has it that it was the Civil War, we took it to mean the Vietnam War, something which loomed large in our lives. We imagined Billy—maybe not much older than us—telling his fiancée that he was going off to defend the country.

We imagined how devastated we would be if that were us. We always put ourselves in the place of people in songs. We cried for her, or with her. We wanted to plead with Billy not to go. From the start of the song, we knew what was going to happen. But we let it lead us there. The anguish, the worry, and then the sorrow. We were with her as she threw out the piece of paper notifying her of Billy’s death in battle. I remember thinking, Billy decided to be a hero. But at what expense?

I heard his fiancée got a letter

That told how Billy died that day

The letter said that he was a hero

She should be proud he died that way

I heard she threw that letter away

My younger sister and my cousins loved this song as much as I did. So we did what any tween kids would do at the time. We made up a sort of skit to go with it. We mouthed the lyrics and did coordinated gestures. My cousin got to be the fiancée; I was Billy and did an exaggerated death scene at the end while my cousins and sister pretended to weep.

It wasn’t enough to make this little dramatic skit. We needed an audience for it. We had to tell everyone the story of Billy and the war. So one Sunday, when we were all gathered together in my aunt’s finished basement for a birthday, we put on a show. There was polite applause at the end of our show, and I remember thinking that adults just didn’t understand art.

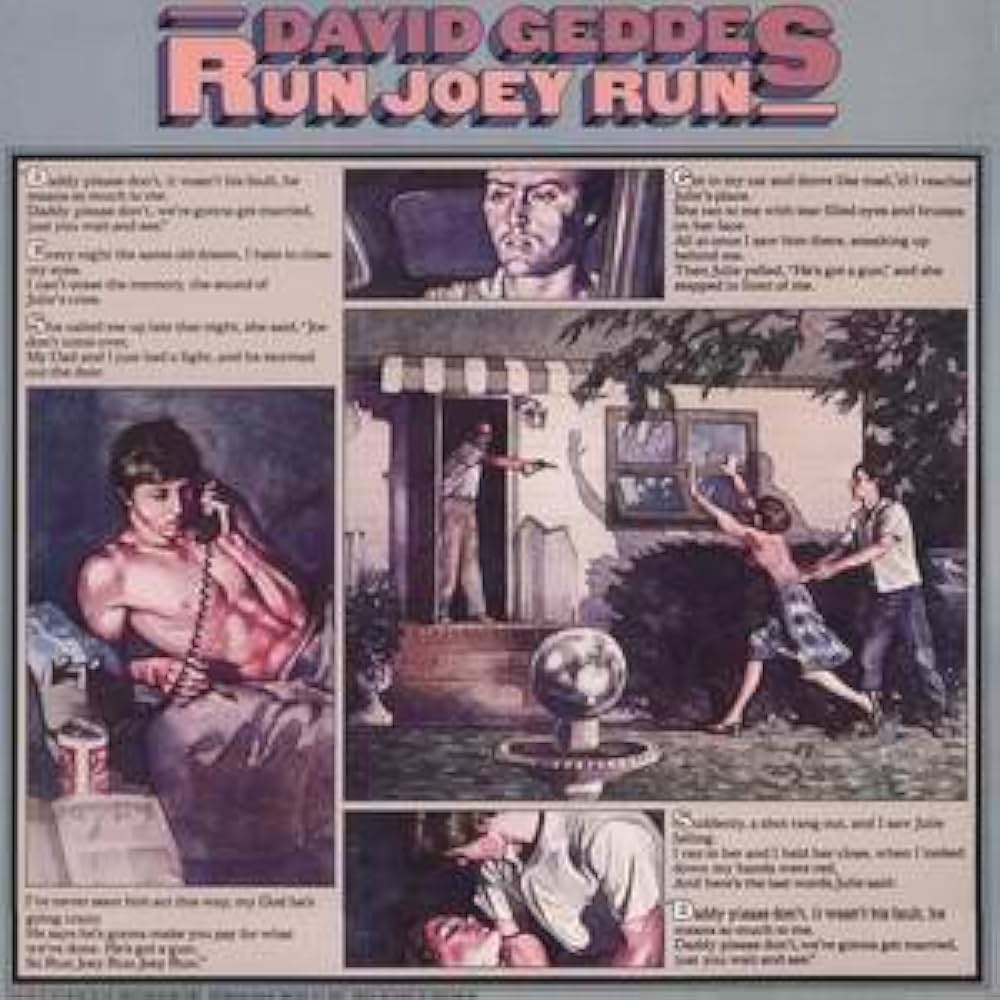

Nevertheless, we did not stop at “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero,” because we discovered other songs that would lend themselves to even more dramatic renderings by 12-year-old girls. Whereas we had once thought “Billy” was the be all and end all of songs we could act out for our captive audiences, we discovered something else: David Geddes’ overwrought teenage tragedy song “Run, Joey, Run.”

Now, keep in mind that we were, respectively, 10, 11, and 12 years old. The whole idea behind the song, though it’s never stated explicitly, is that Joey got Julie pregnant and Julie’s dad was having none of that. He beats Julie and is gunning for Joey. Julie pleads with Joey not to come to her house, but he does. The father confronts them with a gun and shoots at Joey, but kills Julie instead. Julie’s last words are “We’re gonna get married,” but her voice dies out as she succumbs to her wounds.

Suddenly, a shot rang out, and I saw Julie falling

I ran to her, I held her close, when I looked down, my hands were red,

And here’s the last words Julie said

Daddy please don’t, it wasn’t his fault, he means so much to me

Daddy please don’t, we’re gonna get married

The halting, dying cry of “mar…..ried” as Geddes’ voice trails off in a death knell made my cousins sob the first time they heard it.

This is a lot. It’s tragic, it’s sad, and I think it’s supposed to be profound. I found it utterly ridiculous. My cousins cried and I was incredulous. It was just so over the top that I couldn’t take it seriously. However, not one to turn away a chance to act out a song, I went along with my cousins and my sister, and we set about staging a show to the song about abuse and murder. I played Joey. My cousin played Julie. My sister was the father.

We put on this “show” for all of our parents and older cousins one Christmas Eve. It was a packed house, and we pantomimed the song to the best of our ability; my cousins overacted in a very Al Pacino chewing the scenery sort of way. I held “Julie” in my arms while she died, and I pretended to cry before I got up and ran away to the sounds of the record and my sister and cousins singing “Run, Joey, run!”

The show got a good review (they politely clapped), but I do remember some snickers of laughter from the older kids and the horrified looks on the faces of my aunts. The song is really something to be reckoned with. Looking at the lyrics now, from the safe distance of 50 years, I’m amazed this was ever a hit. But teen tragedy songs were nothing new to these adults, who grew up listening to “Leader of the Pack” and “Last Kiss.”

“Run, Joey, Run” was the culmination of our troupe’s little antics. I was close to 13 and moving away from pop and toward Led Zeppelin. And I just didn’t have the necessary seriousness to carry on singing about tragedies. Little did I know that 50 years later, I’d listen to a steady stream of songs about loss, heartache and, yes, death, though none so contrived as “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero” or “Run, Joey, Run.” Thankfully.