Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Ain't That Close to Love - Bowie, Pinball, and Me

by editor Michele Catalano

Pinball Palace was a small, almost hidden place, tucked between the Jerry Lewis movie theater and a specialty bra shop. From the outside, it looked forbidden and dangerous, two things that combined to point a beckoning finger at me. I was around 13 when I first entered the Palace, a tagalong to an older friend who was going there just to score a nickel bag.

Gina opened the door. I followed, hesitantly, knowing that this was exactly the kind of place my parents had warned me about.

As soon as we stepped inside, my brain went into sensory overload. The smell hit me first: cigarettes and pot and teenage sweat, swirling together in the dank heat of the Palace.

Then there were the noises. The clacking of pool balls as someone yelled Break!; the dings and and whistles of the 20 or so pinball machines that lined the walls; the cursing of the bikers at the pool table; the jangling of quarters in the pockets of Levis; the fists banging on the glass as a machine cried out TILT! It was all underscored by David Bowie’s “Young Americans” or Ram Jam’s “Black Betty” shouting from the jukebox. These sounds became my Pied Piper, begging me to follow.

***

Earlier that week, I experienced a landmark moment in my life. I bought an album with my own money. It was paltry allowance money—my parents had intentions to pay us well but I rarely completed my chores—but it was enough back then to afford a $5.98 record. I agonized over my choices, scanning the wall in the record department of Modell’s department store (in the same strip mall as Pinball Palace) for records that were worthy of my own cash.

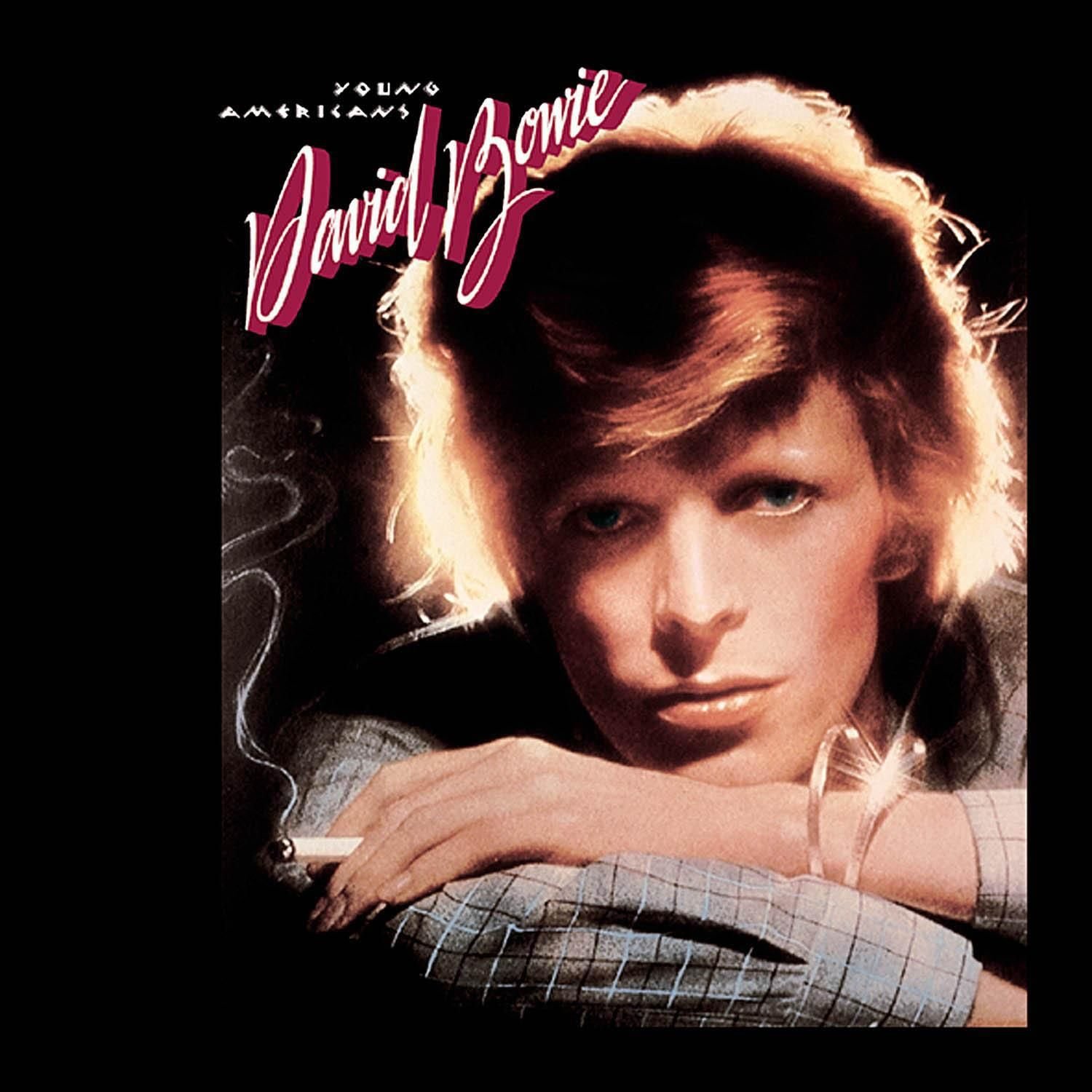

I decided that I should buy a fairly new release. When I spied David Bowie’s Young Americans on the new-releases wall, I knew that I had found my purchase. I was obsessed with the title song; I found it exhilarating, invigorating. I also wondered how much cocaine Bowie did before recording it. It was a good pick for a first album. I spent a lot of time looking at a wistful Bowie smoking his cigarette on the cover. Dreamy.

***

I was shy that first day at the Palace, hanging back while Gina did her business with a guy at the change counter. Gina had little interest in pinball itself. The Palace was a means to and end for her. When she was done, we went behind the movie theater to smoke a joint, then snuck in the back door of the theater. They were showing Shampoo. We watched Warren Beatty, naked on the floor, humping the daylights out the poor girl underneath him (all I can remember is that a person was watching them through a window), and he said something like “Now that’s what I call fucking!” I was embarrassed to be there. Gina sat gaping at the screen, taking in every word, every movement, probably taking notes in her head. All I could think about was going back to Pinball Palace, to the clanging of the machines, to Bowie on the jukebox.

The next Saturday, Gina took me with her for another buy. This time, I brought quarters. While Gina flirted with her dealer, I made the walk towards the machine in the far corner. The Bally Wizard.

****

Young Americans was a defining record for me at that time. It was unlike anything I listened to. It made my year. Why, I don’t know. I just felt this yearning for something different when I listened to the album. I was used to the pounding rhythms of Zeppelin, the anthemic music of The Who. I didn’t know what to make of Bowie. I wasn’t sure why I liked it so much.

***

That first time, I hesitantly put my money in the pinball machine, knowing full well that I would become addicted to the flashing lights and turning numbers. The quarter dropped. I hit the reset button. The silver ball popped into place. I slowly pulled back the lever, feeling the resistance of the coiled spring. I let go. The tip of the lever and the metal ball connected. And as that ball went around the curve on its journey towards the playing field, it took with it my grades, my social life, my allowance. When I heard the machine ring up my first score, I was hooked. Ding!

My fingers worked the flippers as deftly as the lady in the school office worked the typewriter. I moved this way and that, swinging my hips and nudging the machine a little to the left, a little to the right, careful not to piss it off enough to make it tilt. My eyes darted between the ball and the scoreboard, and my heart skipped a beat when I saw the paper taped to the top of the glass with the high scores for the week. My name would be up there one day. Yes, it would. I put a quarter in the jukebox. “Young Americans" eventually popped up again, much to the chagrin of the bikers, who preferred “Black Betty.”

Gina had to drag me out of the Palace. Even when my quarters ran out, I wanted to stay and watch the masters play; the guys who turned over the numbers on the scoreboard, the guys who could smoke and drink and play at the same time.

Suddenly it wasn’t just Saturdays. I started walking to the Palace after school. If Gina wouldn’t go with me, someone else was always willing to hang out and watch me play pinball instead of going home. We would throw a few quarters into the jukebox (three plays for twenty five cents!), and play the same lineup each time. Led Zeppelin. Todd Rundgren. Bowie. (I never did like “Black Betty.”) I started playing “Fame” instead of just the Bowie title track, and the bikers seemed to appreciate it.

I would sometimes ask my mother for a ride to the library and, when she pulled away after dropping me off, would run across Front St. and duck into the Pinball Palace. I rationalized my lying. I wasn’t out doing drugs—no respectable 13-year-old considered pot a real drug, not when other people’s kids were doing angel dust—and I wasn’t out getting pregnant, like Mrs. Winslow’s daughter. I was just playing pinball and listening to David Bowie and getting free pool lessons from the bikers.

The frequency of my trips to the Palace waned when winter dug in its heels, and nobody wanted to walk that far with me. Occasionally, we would get a ride to the movie theater and instead slip inside the Palace. Every time I walked through those doors was like the first time; the smell, the sounds, the pumping of adrenaline would all feel new again. I would, out of habit, head for the jukebox and play the trifecta of “Young Americans,” “Fame,” and Led Zeppelin’s “Trampled Under Foot.”

They closed Pinball Palace before the good walking weather came back. Neighbors were complaining. Community action groups were picketing. Churches were praying for the souls of the kids caught up in the glare of those flashing lights. They claimed Pinball Palace was a haven for dirty, unkempt teenagers, who cursed and drank and smoked and listened to the likes of Bowie. It was stealing the life and soul of the community’s young adults.

I cried. I mourned. I lay in bed at night, my fingers twitching to imaginary flippers, the game playing out in my mind. I had to find another place.

That summer, my parents sprang the news on me that they were taking me out of the “terrible” public school system. They didn’t like my friends. They didn’t like my attitude. Catholic high school would surely lead me on the path to a righteous life. (Reader, it did not.) I would make new friends, they said. Friends who wouldn’t drag me to those filthy pinball places. Friends who wore skirts and ties and gave their quarters to the collection basket instead of machines.

By the end of the second week at the new school, I had made a few new friends, just as my parents wanted me to. Mom let me stay after school each day and take the late bus home, assured that I was sitting quietly in the cafeteria with my new virtuous friends, studying and doing homework.

Not quite. See, the 7–11 across the street from school held a deep, dark secret in its back corner: a Bally Wizard pinball machine. My new friends, who hated ties and skirts and hoarded their quarters like gold, would watch me play for hours each day, taking bets on if I would break the high score. I had a following. I was the Pinball Wizard. Catholic school was working out just fine.

Sure, 7–11 wasn’t quite the same as the smoke-filled Palace. But Kevin did bring along a portable cassette player each day, and we listened to Bowie and Zeppelin while I swished and swayed and occasionally tilted.

Pinball eventually gave way to other video games: Asteroids and Galaga and Space Invaders. Arcades started popping up everywhere. My pinball skills were no longer celebrated, and I quickly became a has-been, a thing of the ancient past.

I never regret all those hours and quarters spent feeding my pinball frenzy. I never regret the time spent learning the exact angles of each machine, or feeling the excitement when my name went up on the high-score chart.

I visited the Pinball Museum in Las Vegas in 2016, more than 30 years after my initial fascination with the games. Almost all the old games were there—the Who’s Pinball Wizard, KISS, Twilight Zone, and Elton John’s Captain Fantastic. I got 10 dollars’ worth of quarters and hit the Who machine first.

At the drop of the first quarter, it all came back. I closed my eyes for a second, putting myself back in front of the Bally Wizard at Pinball Palace. I pulled back the lever, felt the spring hit the ball, the lights and sounds went into action, and I furiously hit the flippers. I was in my glory.

Three seconds later, the ball was sinking out of sight between the flippers. Apparently, I no longer had the magic. All those quick reflexes, gone. I played those ten dollars on various machines and had a great time doing it. But I realized that you can’t go home again. Maybe what I was missing was Young Americans playing in the background.

I watched a kid, maybe 12, stick a quarter in a shiny, new Game of Thrones machine. His father watched as he worked the flippers, the kid’s face full of concentration and determination. There was a whole row of brand new pinball machines based on current movies and bands and sports; all had little kids playing them, taking in the sights and sounds the way I did all those years ago. The father smiled at me while I watched his son play. “Passing the torch,” he said.

I smiled back. It was good to see all the new machines, good to see pinball still alive and well, kids enjoying the games. There aren’t a lot of arcades out there these days. There are certainly no dank, smoky Pinball Palaces. But I have a glimmer of hope that the art of pinball isn’t quite dead.

After a while, I stopped listening to Young Americans, save for the title track, which I had taped onto a cassette four times in a row (I guess I thought four was the correct number of times to listen to it). Bowie was for pinball, and pinball was no more. But every time I listen to this album—which I’ve been doing more frequently lately—I am brought back to a time when pinball was king, and I ruled its Palace.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal