On Peter Gabriel's "Melt" and Steve Biko

Published on Feb 21, 2026

Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Elvis, My Mother, And Me

by editor Michele Catalano

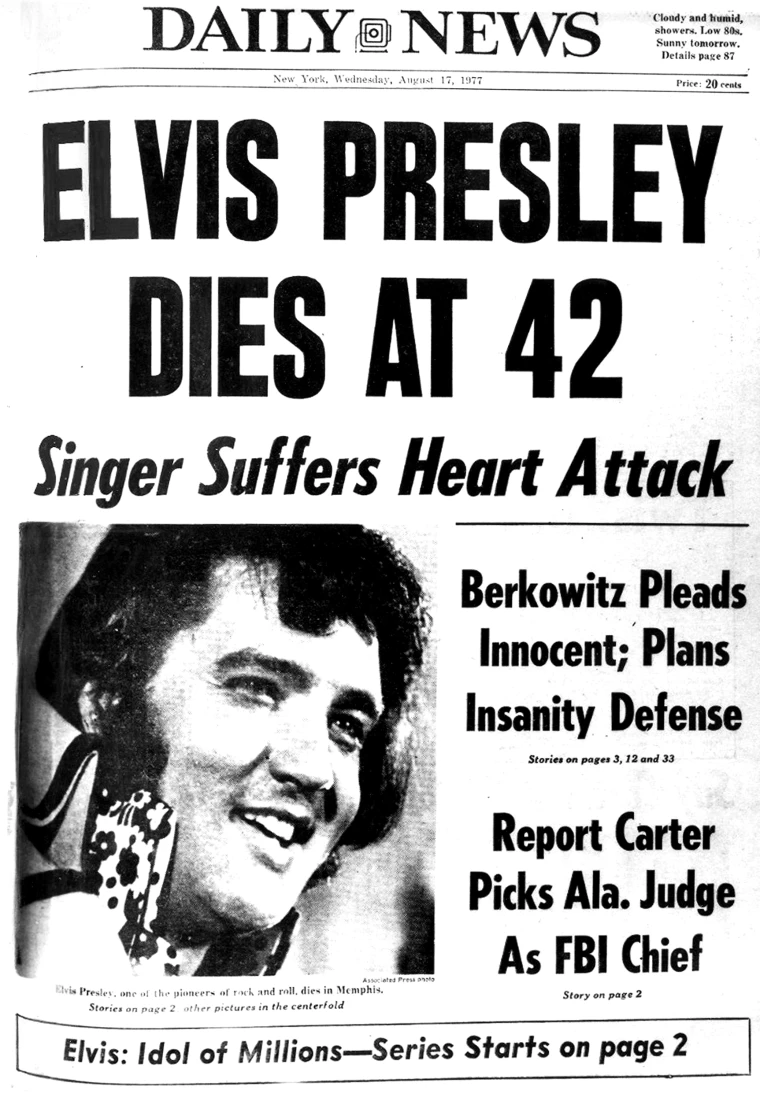

It was one of those moments when you say something you know you shouldn’t. But I couldn’t help myself. I was fourteen and still in the throes of teenage-girl-smart-ass disease. I was sitting in the backyard 48 years ago, listening to the radio, when I heard the news. I went inside and found my mother in her room, making her bed.

“Hey, mom. Guess you won’t be going to that Elvis concert next week.”

“What?”

“He’s dead.”

I may have snickered, I don’t know. Mom ran and turned on the little radio she kept in the bathroom. I remember the tinny, staticky voice that relayed the news to my mother in a much softer way than I did. Elvis was dead.

My mother’s eyes filled with tears and despair. Her face registered nothing but that small “o” your mouth makes when you hear shocking news. That “o” stayed there for a while, but the despair in her eyes had become hard and angry. She was pissed at me. How could I have told her like that, knowing that she idolized Elvis in a pure, passionate way? How could I do that? What kind of daughter was I?

Well, I was fourteen. That’s my only excuse. I was a fourteen-year-old whose mother made fun of her own idolization of Jim Morrison—another self-obsessed, overly dramatic singer, who similarly became a bloated replica of himself. And later, dead and bloated. Maybe it was my way of evening the score.

My mother had a friend named Noreen. Noreen was the largest woman I ever knew. Not just heavy but tall and broad and wide, with thick, teased hair piled up on her head, which made her look even taller. Her voice roared, even when she whispered, and her sneezes were legendary in the neighborhood, rumored to have been heard from at least three blocks away. She wore mumus and housecoats and tons of hairspray, and she sometimes wore an ugly fur coat that made her look as if a small woodland creature was nesting on her shoulder.

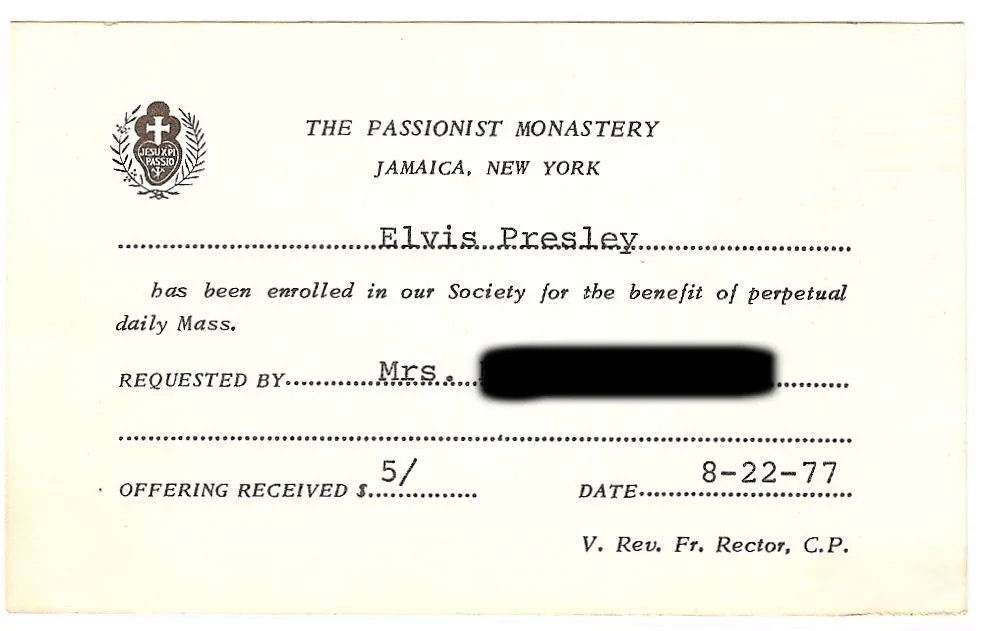

Noreen and my mom were the Elvis duo. They worshiped him. They loved him. They knew everything about him and owned everything to do with him, including Elvis commemorative plates. I think one of them had an Elvis wristwatch.

I grew up with Elvis’s hips grinding in my face and his voice grinding in my ears, and I have to admit that, at some point, I realized what the attraction was. I would lie in bed on summer nights, trying to sleep while my mother and Noreen and the rest of their crew played Pinochle in the kitchen with Elvis on the stereo. His voice would come drifting into my room, and I could feel the sensuality, and the passion within his words.

Of course, I would never tell anyone this. I went about my daily business of bowing before Jim Morrison and Robert Plant and never let on that I thought Elvis was cool. Especially to my mother. That would just ruin the taut, tenuous relationship that we both thrived on. Who was I to break the rite of passage of mother-teenage daughter bitterness and anger?

Noreen and my mother were going to see Elvis in August 1977, at the Nassau Coliseum. They had seen him many times before, but this one was special. They had a feeling that this would be his last tour ever. They were like little giddy schoolgirls in the weeks leading up to the show. Sometimes my mother would take out her ticket and just stare at it.

She was 39 at the time. When I was fourteen, 39 was old and withered and wrinkled. Thirty-nine was too old to be getting worked up over a hip-shaking idol. I thought it was kind of creepy. Funny how that works. I’m now 62, and I’m not old or wrinkled or past getting worked up about my musical idols. And there I was, a stupid teenager looking with disdain at her mother for being excited about seeing Elvis.

Then there was no Elvis.

She had been so happy. And I crushed her world. It would have been a much softer blow if it had come from Cousin Brucie or Uncle Somebody on whichever oldies station she was listening to. It would have been a bit easier for her to take if her teenage bag of hormones hadn’t made some smarmy remark about Elvis dying like a fat, beached whale.

The news of Elvis’s death spread around the neighborhood. It was as if my mother’s sobbing set off some kind of Bat signal, and you could hear wails of anguish coming from housewives all down the block. When Noreen found out, we heard her bellowing from two blocks away. Her booming voice sounded through the neighborhood like a siren, a mourning call for all Elvis fans to gather on her lawn and weep. It was a sad day for Elvis fans, and all I could think to do was make fun of them.

I don’t think my mother ever told Noreen how she found out about the death of their hero. I probably wouldn’t have lived to tell this tale if she knew. She would have beat my ass, and an ass-beating from Noreen was unlike any other. I suppose I owe my mother for saving me from that.

When Noreen died, my first thought was that she would finally get to see Elvis again. My second was that I was now safe from my mother ever spilling the beans to Noreen about my youthful indiscretion. I had lived in fear all those years. Hell, sometimes I still think the ghost of Noreen is going to appear all these years later, wearing a sequined white jumpsuit, hell-bent on haunting me.

I thought my mother had forgiven me, but judging from the look she gives me whenever the story is brought up again, perhaps not. Maybe that’s what drives every argument we have. Maybe she’s still mad at me.

I have since apologized to her. I told her I was sorry for breaking the news like that. But in a way it was her fault for making me sit through Viva Las Vegas and Jailhouse Rock, for forcing that horrid “In the Ghetto” on my ears, for making me try fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches.

I eventually watched the new Elvis movie and enjoyed it. My mother had seen it in the movie theater, and we discussed it over breakfast one day. Of course, we got around to talking about the day he died and “the Elvis incident,” as I like to call it. She gave me the look she always gives me when the story is brought up, that disappointed look only a mother knows how to give. I guess she still hasn’t forgiven me. I don’t blame her at all.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal. Tips go toward paying writers, an editor and for site maintenance