Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

Happiness I Cannot Feel: Black Sabbath's "Paranoid" and the Turmoil Within

by editor Michele Catalano

I was eleven years old when I first heard Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid.”

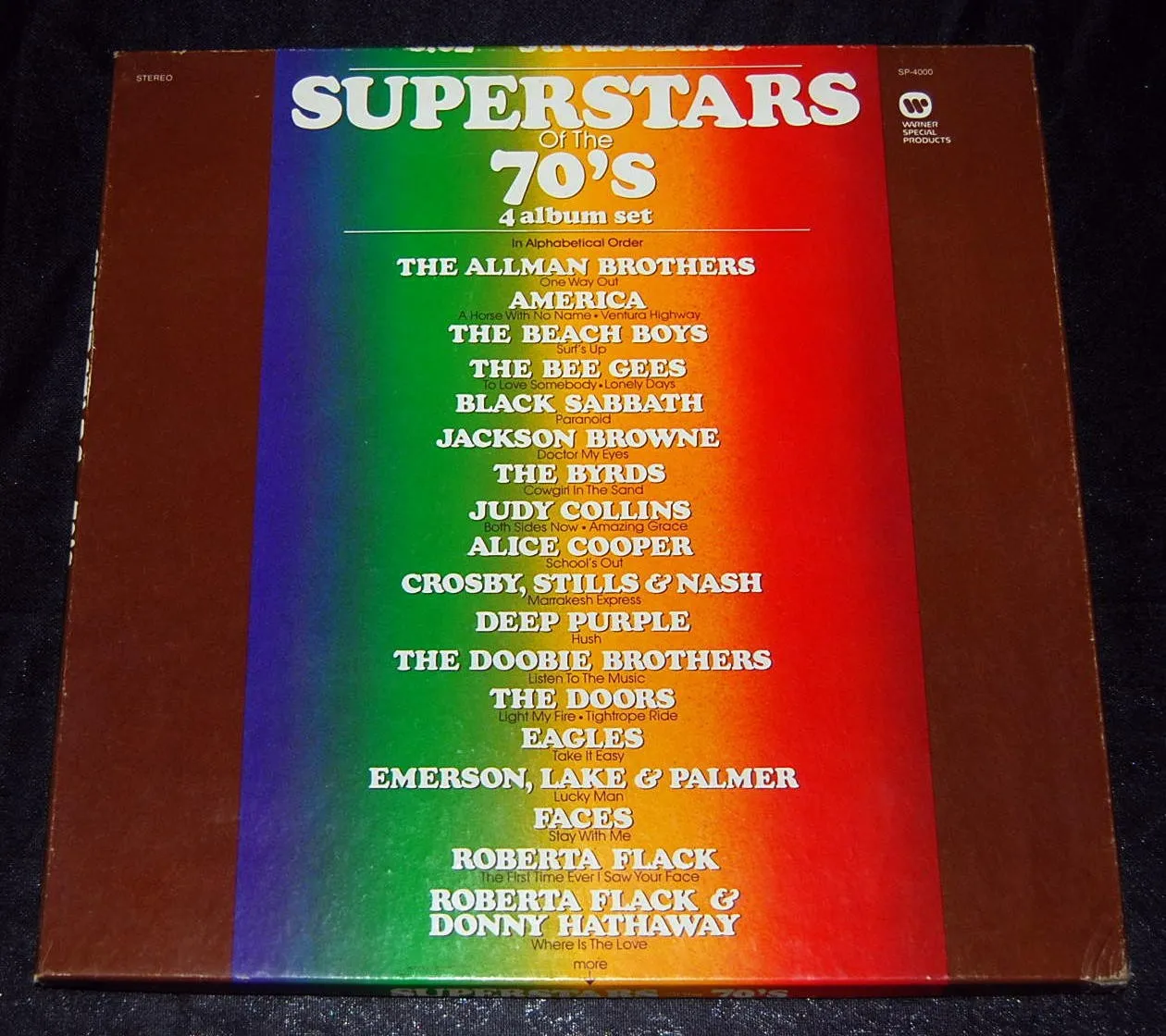

I don’t think anyone intended for me to hear it. A well-meaning cousin bought me a compilation album called Superstars of the 70s. I think he wanted me to listen to certain tracks, help me discover the music he liked. The Beach Boys. The Doobie Brothers. Crosby Stills and Nash.

At first I gravitated toward the Yes cut, a three minute version of “Roundabout” (and I would only later discover there was another 536 minutes of the song). There was Hendrix and Deep Purple and various other hard rock songs — all edited down to a radio-friendly three minutes or so — that excited me as I worked my way through both sides of all four discs.

It was when I got to the end of the third disc that my relationship with music was forever changed. Before this moment, I had a clearly defined world view of music. I knew soft rock. I knew hard rock. I knew pop music and protest music and all the music that fell between those loose ended genres. Music was meant to move you, to stir you, to take you out of this world in much the same way books did. But it was a grounded thing, as well. I could listen to a song and really feel what was going on in the lyrics but still be in the here and now, in my bedroom living vicariously through whatever words and tunes were seeping into my headphones until the music stopped and whatever I felt at the moment was over. Music was for me, at that moment, simply a medium. Yet I knew. I knew there was something I was missing, something more about it, that thing which made my older cousins talk seemingly nonstop about the bands and songs they loved. I, too, loved songs and bands. But at eleven years old I had yet to find something to pull me all the way in, something that would make me exclaim “Holy shit, listen to this!” the way my cousins did.

I knew there was a connection to be made between music and myself but I hadn’t gotten there yet. There was nothing yet that had reached out a hand and pulled me into its world. But I was going to find it on an album called Superstars of the 70s. I had a feeling. It was in there somewhere.

Seventh side, last song.

“Paranoid.”

The second it started I felt like I wasn’t supposed to be listening to it. This was something my parents would want to keep away from me, a song meant for older kids with much more life experience and an understanding of the world than I had. It made my pulse quicken. It made my hair stand on end. There was something in Ozzy’s voice, in that pulsating rhythm, in the pace, the words and the sheer darkness of the song that made me pick that needle up at the end and play it again and again and again.

“I didn’t know music could sound like this,” was what I kept thinking. “I just didn’t know.” But what I did know on that winter night was this: I had found it. I found the hand that reached out, grabbed me and pulled me in. And in that moment, the way I listened to music and what I listened to changed forever.

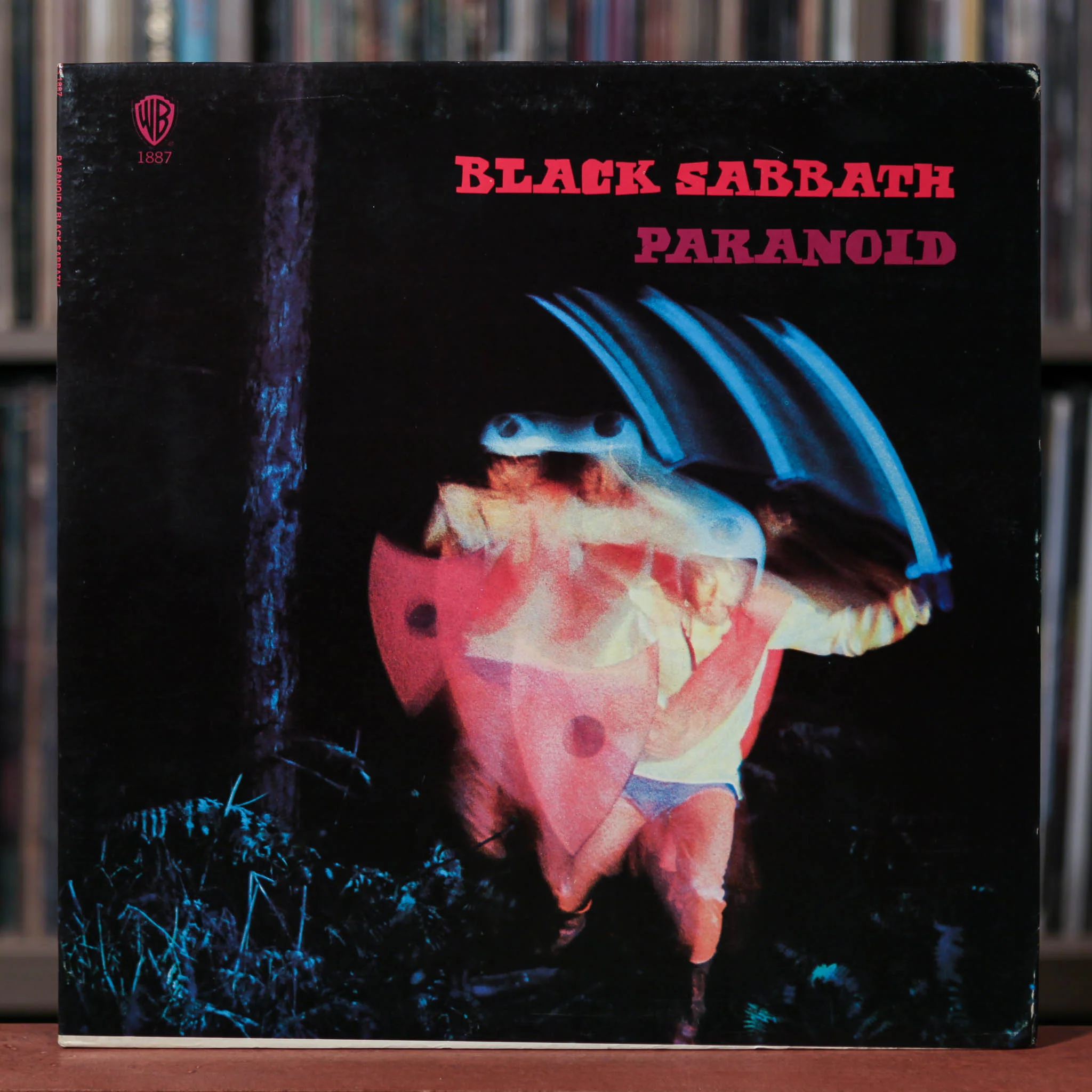

On my next trip to Modell’s Department Store with my mother, I left her in the housewares department while I ran over to the records. Yes, parents often let their kids loose in large stores back then. We hadn’t yet come to the era of Stranger Danger. But little did my mother know what danger did lurk in that store — Black Sabbath’s Paranoid.

I was afraid to ask her to buy it for me. I thought she’d say it was evil or horrible or just too much for me at this age but my mother was either blissfully ignorant about Black Sabbath or was just so eager to pass her passion for music on to me that she easily gave in and bought me the album.

I waited until after dinner, until it was sufficiently dark and quiet so I could familiarize myself with the album under the proper conditions. I put on my headphones and held my breath.

Generals gathered in their masses

Just like witches at black masses

What transpired between myself and my record player that night can only be described as a transformation. My dear, innocent stereo, mostly resigned before this evening to be the spinner of records soft and harmless, was now a vessel of darkness. And it thrilled me. With each song, I felt changed. I felt older, wiser, more in tune with what the world out there held for me. I felt like I was finally understanding music. Everything I listened to before this was just simplistic preparation for the real thing, a primary school before my real education was about to begin, in a night long class taught by Black Sabbath.

Oh, I had no idea what Ozzy was singing about. I was eleven. Most of the meaning within the songs eluded me. But I could tell. I could tell from the music and the tone and the words used that this was different than anything I’d heard before and I was damn sure none of my eleven year old peers had beaten me to this discovery. I was a trailblazer.

Yet it’s hard to blaze a trail when you keep things to yourself. And that’s what I did with Paranoid. I didn’t share it. I was already a bit of an outcast and playing “Faeries Wear Boots” or “Hand of Doom” or “Iron Man” for them would probably only serve to have them sever their already frayed ties with me.

So I sat in my room by myself night after night, trying to decipher the messages within, feeling like even though I wasn’t sure what Ozzy was going on about it was still somehow important to me, that he of all people would know what it was like to have friends who weren’t really your friends, to spend nights alone contemplating the meaning of life, to feel like your place in the world is undefinable. Not just Ozzy but all of them as a collective, Ozzy and Tommy and Geezer and Bill — I didn’t know their names then but I made damn sure I found out who my new friends were — they knew of the darkness that lurked around the edges of my emotions constantly; not a poetic darkness, not one that earnest boys in sweaters write about, but a deep, prevailing darkness that kept me from being truly happy with myself or who I was, a darkness that let me know there was evil in the world and sometimes that evil was born of underworldly things and sometimes that evil was born of your fellow man. Or children, as it were.

Oh, yes. Existential crisis at eleven? I was born into one. Listening to this form of music only elevated that feeling, but I didn’t care. It’s what I wanted. It’s what I had been looking for when I first laid the needle down on Superstars of the 70s, hoping there would be one small thing within that would reach out and grab me and take me away with it.

I would never listen to music in the same way again and what I would choose to listen to from there on out had drastically changed course.

There would be other albums, other bands that would make me feel the passion for music the way Paranoid did, but I’ll never forget my first foray into the dark. It showed me the light.