WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

Christmas Music Selections

Published on Dec 14, 2025

More Liner Notes…

You Should Be Dancing

by editor Michele Catalano

Of all the years of my life,1977 is the year I could tell you the most about. It was a time so packed with intensity and emotion and drama; I don’t recall any other year of my life being quite like that one. Of course, I was barely 15 at the time, and there’s enough emotion and insanity inherent in that alone to make the year worth telling about. But there was something so different about 1977, especially the late spring and summer. Especially in New York.

New York City was just coming out of terrible times—there had been a huge financial crisis, and, for the longest time, the South Bronx was literally on fire. Back then, my father was a fireman. He was always talking about how there would eventually be no fires left to fight in the area because it was all going to burn down. Bushwick, where my father worked, was no better.

It was a constant battle to stop the fires and the emotional fire that was spreading throughout the city. As the heat rose, tempers rose. There was a general feeling of unrest that made my father dread going to work. It wasn’t just the flames; it was the feeling that there was something else about to explode besides empty tenements. My parents discussed all this at the dinner table with us. As we watched the nightly news together, we watched New York City almost die before our eyes.

Between the oppressive heat and humidity and all that was going on around me, I felt a sick sense of dread that summer; but it was a dread tinged with a curious excitement. There was so much electricity in the air, you could almost hear the crackling of static when you woke in the morning. And it was so damn hot. It was the first time that, when my mother said this heat could make people crazy, I didn’t hear it as a cliché at all. To me, it was true.

The relentless swelter had gotten to all of us, kids and adults alike; we were short-tempered and cranky and prone to starting fights over nothing. We were living on the edge, and we all knew it. I think we aged five years that summer, all 14 and 15 but cynical and hardened in many ways: from having so much death and tension and raw energy shoved in our faces every day, to the newspaper headlines about Son of Sam or the New York City blackout or the despair of New Yorkers, to our shell-shocked parents hammering us with statistics and warnings.

We were living all this out with a soundtrack, huddled in the abandoned house next to the high school or in the sump or in someone’s garage every night, listening to this bizarre mix of the Ramones and Sex Pistols, Kiss and Foghat, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Queen. We were all revved up with no place to go, just some green-grass and white-picket-fence kids both fearing the world we were living in and wanting so much to be an intrinsic part of all that fear; to be in there, at some punk club or on the quiet streets of Brooklyn, looking for a serial killer. We settled for drinking cheap beer, smoking stolen cigarettes, and alternating our disaffected-youth rock music with the sounds of baseballs being hit out of Yankee Stadium.

There was also disco. Disco was, depending on whom you talked to in 1977, either the greatest form of music ever or an outright abomination. My friends were on the side of the latter, and I obliged by wearing a “disco sucks” button and turning up the punk.

There was only one problem: I really enjoyed disco.

***

After the Son of Sam was caught in early August, people went back to feeling complacent, if not safe. We tried to ride out the rest of the summer by getting back to the business of being kids who didn’t think about things such as men who stalk and kill or blackouts or a city’s financial crisis. And we tried. We hung out, we listened to records, we watched baseball, we went to the movies, and we started and ended teenage romances. Some of us went to summer school during the day because we didn’t pay attention in 9th grade biology. I couldn’t wait for the summer to end.

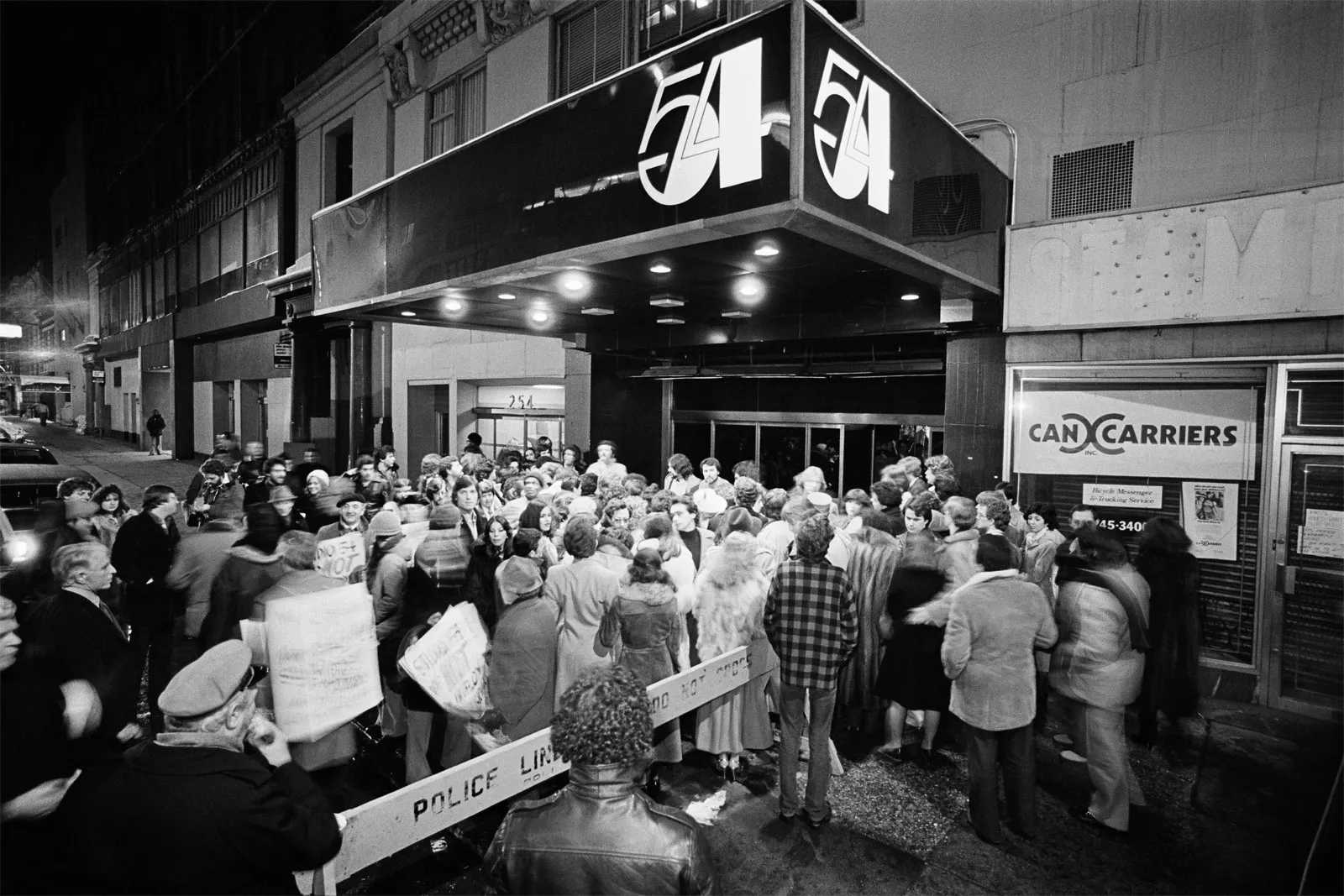

I spent a lot of my alone time in my room, listening to disco and feeling somewhat ashamed, as if I was betraying my friends. I was listening to Chic, KC and the Sunshine Band, Rose Royce, and Tavares. I loved the slow-dancing disco as much as the fast-dancing tunes, and I moved around my room like I was in Studio 54, minus the cocaine. I didn’t tell a soul.

It was a pretty big surprise when, over Christmas break, my friends said they wanted to go see Saturday Night Fever. Christie’s brother worked at the movie theater and would get us into the R-rated showing. I was thrilled, but I tempered my reaction and gave an almost noncommittal shrug when they asked. I couldn’t let on, but I couldn’t wait to see this movie. I’d been reading about it for so long, knowing I couldn’t really ask my punk and prog friends to go see a disco film. But there we were, on a weeknight, being slipped into an almost full theater. I was so excited.

The movie sucked. I hated it from beginning to end. But that’s fine because I wasn’t there for the movie. I was there for the music, for the dance scenes, for the Bee Gees, for the vibe. It was a struggle not to get up and move around with the music, as I did in my bedroom. I left the theater satisfied and even more energized about loving disco. The next day, my mom took me to Jimmy’s Music World, and we bought the soundtrack for the both of us to listen to. It lived at night in my room, where I played it over and over again, dancing with myself and thinking that my Todd Rundgren poster would laugh at me. I held that album in such high regard, perhaps because it belonged to me and me alone among my friends. It was my secret.

Time seemed to go into fourth gear after 1977. Suddenly, it was 1980. I was graduating, and that summer of fear and tension faded away in the rear view mirror at an alarming speed, taking disco and Saturday Night Feveer with it.

A few years ago, I came across the soundtrack while looking for something else at the record store. The nostalgia hit me like a brick to the head. I picked it up, held it, and turned it over in my hands. I thought back to those nights in my room, dancing to “If I Can’t Have You,” twirling myself around, imagining I was in Studio 54. I bought the album without looking at the price.

I got home and eagerly opened it up. I inhaled deeply, as if nostalgia is a real, tangible thing, and I could breathe in its particles. I wanted to bottle this. I wanted to keep this feeling forever, this all-encompassing sense of freedom, of rebellion and growing up, of being fifteen.

The film’s music had taken that feeling and turned it into a sound for 15-year-old me. While everyone around me was wearing their “disco sucks” buttons and calling the music simplistic, I had found strength and power in it. I had found rebellion and freedom in it. Disco had seemed, to me, more of a partner to punk than an enemy of it. But none of my peers wanted to hear that, or even know that I was thinking about such a thing. So I listened to my album alone, on headphones, ashamed.

I feel sorry for 15-year-old me, that she didn’t get to fully enjoy the album, or disco at all, that she felt she had to hide it for everyone. I’m listening to it now for her, for 15-year-old me. I have it turned up, and I’m going to dance around my living room and think about all that pent up fear and anxiety of 1977, how that all disappeared every night when I went to Studio 54 in my head.

It’s funny how I thought at the time that 1977 would go down as the most tumultuous year of my life. Listening to Saturday Night Fever now, hearing these familiar yet nostalgic songs, recalling the mild terror I felt that summer, I can laugh a little about my naivety. It gets worse. It always gets worse. A little disco makes it better.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal