Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair

Published on Jan 19, 2026

WALK OUT TO WINTER: falling in love with—and to—Aztec Camera's High Land, Hard Rain

Published on Dec 26, 2025

First Anniversary

Published on Dec 17, 2025

Introducing: The IHTOV Zine

Published on Dec 15, 2025

More Liner Notes…

You're So Viscious: a tale of friendship and Lou Reed

by editor Michele Catalano

She was younger but knew all the cool music before I did, thanks to her older brothers. We’d sit in her room, and she’d play records for me and rattle off facts about each album, each song. Sometimes the songs were new to me, sometimes they were familiar. We’d always have a conversation about the songs, listen to them again, talk about them some more. She’d write lyrics down in a spiral notebook when something felt particularly meaningful to her. Then we’d dig deeper into those lyrics, our conversations about them often revolving around ourselves, our own lives.

Allison was an emotional girl, which is why our friendship was at times so deep yet so volatile. Two teenage girls with no control over their emotions—two girls prone to anxiety, overthinking, and bouts of depression—were bound to have their moments of histrionics when spending so much time together.

That tiny bedroom where our friendship blossomed at times became too closed and confined. Allison had too much control over the record player. Allison was sure her reading of the lyrics was correct. Allison was hell-bent on playing Elvis Costello’s “Alison” five times in a row, every day, pretending it was written for her, crying over a lost relationship she created in her head. I’d want to change the record; she’d want to keep on crying.

Sometimes we’d leave her room and go sit on the stone wall in her backyard, a wall that abutted a field of dead grass and wayward leaves. We’d be morose then, smoking her mother’s Marlboro’s, sighing as we exhaled, talking quietly about the constraints of our lives and how hard it was to just be. We usurped all our musings on life from the song lyrics of our heroes, fitting them into our own meager lives, acting as though we knew—at 14 and 15—all those trials and tribulations contained within the songs we loved.

At some point, Allison gave up on listening to her namesake song five times a day. She’d found a different song; one that had less meaning to her, if any at all. But she’d become hung up on it, the lyrics scrawled in her tiny, shallow handwriting, squeezed on the page underneath the lyrics to “Alison,” as if they had some connection.

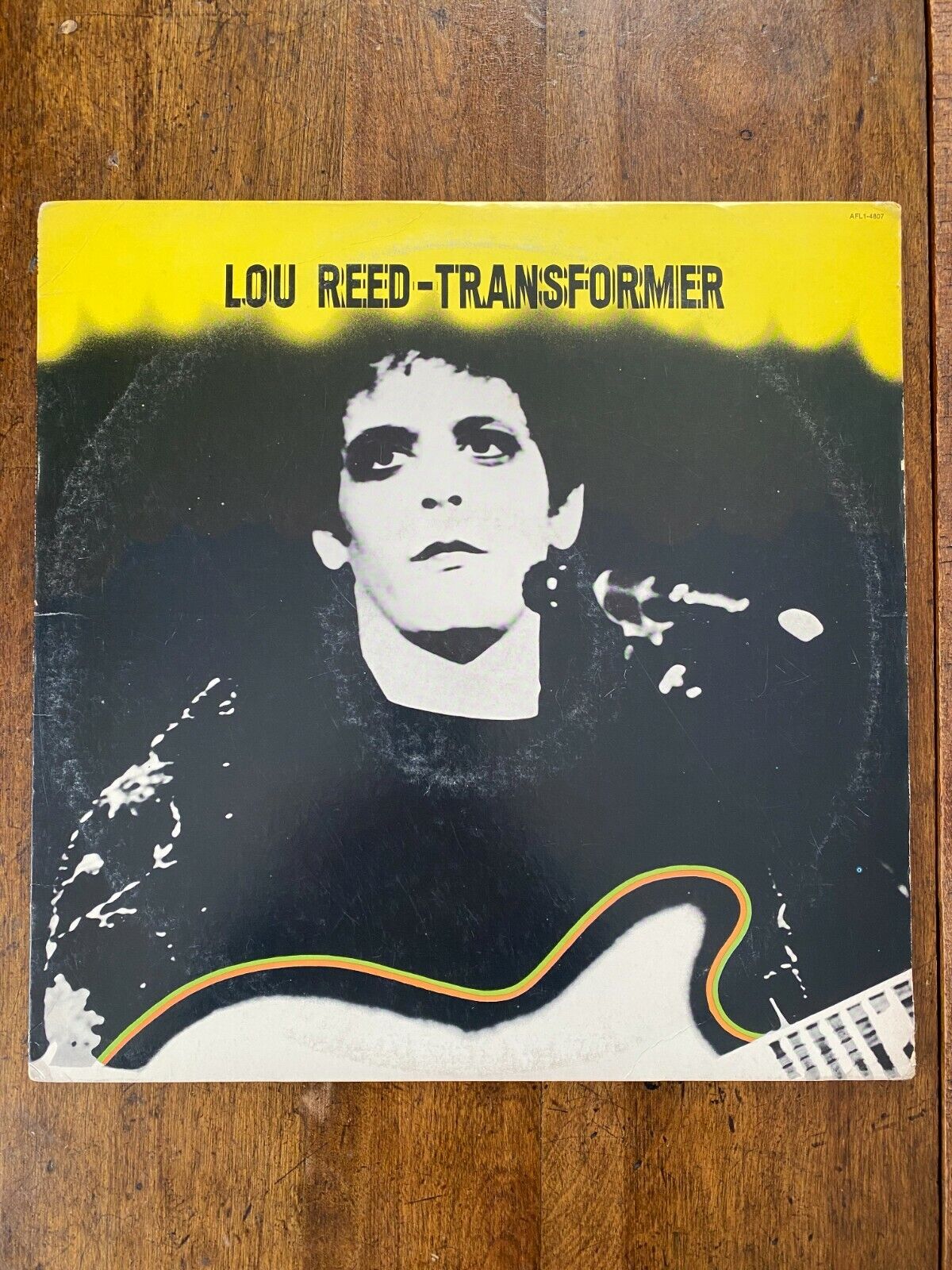

“Listen to this,” she said more than once. And I listened as she played Lou Reed’s “Vicious” over and over, drumming her fingers on her knees as she sat leaning against the wall, legs scrunched up against her, lost in a world where “You hit me with a flower” was meaningful and deep. It became my favorite song as well.

Having finally found a song we could share an obsession over, we listened to it endlessly, singing it with a mutual glee. We also listened to “Perfect Day,” and, of course, “Walk on the Wild Side,” which we had memorized from the days before we knew each other. We did the whole album, side 1 and side 2, but we always came back to “Vicious” for another serving. It made us feel something other than the peculiar angst the rest of the album afforded us.

The last time I saw Allison, we spent some time sitting on the wall, smoking, talking about the hard lives we presumed to live, how bleak the future seemed when viewed through the kaleidoscope of song lyrics written by our elders—lyrics we always took as a warning of the heartbreak that would follow us around forever. Love was the most dangerous game, we decided. We weren’t going to play. We sang “Vicious” out loud, laughing at how ridiculous we made the song sound, apologizing to Lou Reed while we laughed and sang.

And then Allison was gone. She took her record player and her albums and 45s and moved to her father’s house. I only found out through her mother. Allison never told me she was leaving, never said goodbye. Just like that, the connection was severed.

I cried the way one cries after a breakup. Who would I talk to about music? Who would listen to songs with me with that kind of obsession? Who else would understand me? I’d forged this relationship with Allison that I thought would last forever. So many relationships are bonded with tenuous, intangible things. But we had music. Music was something you could hold in your hand, as well as in your heart. A relationship based on that should never have to end.

But it did end. I never heard from Allison. She never called, never wrote. Her mother told me Allison had a nervous breakdown, and it was important for her recovery to sever all ties with anyone and anything that came before. She was starting fresh. I imagined Allison in some stark, white room; a room without windows, without a record player, without Elvis Costello and Lou Reed. I cried for her, even though she would be mad that I did.

The day I realized I’d never see Allison again, I went home and put on Transformer, thinking I would just cry and put the album away forever. But as soon as the opening notes to “Vicious” played, I smiled. I sang along.

I didn’t have Allison anymore, but I’d always have this. Things come and go. People come and go. Music is forever. And shared music embeds itself in your soul, lets you emotionally maintain connections that should have long since been forgotten.

I’m thankful to have this memory that comes riding on the back of a song. It’s the way all memories should ride.

I Have That on Vinyl is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy what’s going on here please consider donating to the site’s writer fund: venmo // paypal